Prisoners of War in the Sol Feinstone Collection

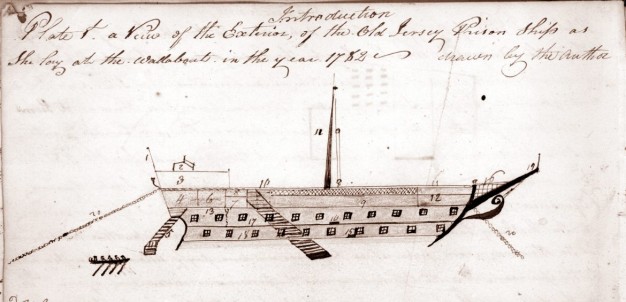

HMS Jersey drawing is from Recollections of Life on the Prison Ship Jersey. APS.

The American Philosophical Society houses the Sol Feinstone Collection, a rich archive of letters and documents related to prominent American and European figures from before the American Revolution until the 1850s. The Feinstone Collection includes letters from George Washington, the Marquis de Lafayette, as well as commanders and soldiers during the American war, making it an invaluable resource for military historians.

Victories came with a cost during the American Revolution. Prisoners of war taxed both material and human resources, and their treatment carried diplomatic consequences. American military prisoners kept in the stinking hulls of British prison hulks, like the one pictured above, have enjoyed a staying power in the psyche of historians and history enthusiasts alike. British-allied prisoners, however, have received considerably less attention. Though their stories often contain markedly less death and disease than those of captive Patriots, studying their treatment by various American authorities reveals important insights about wartime in the newly united colonies. Diplomatic imperatives, the interplay of civil and military authorities, and the non-combatants experience of war are all reflected in the captivity experiences of the British-allied soldier.

Several letters in the Sol Feinstone Collection trace the development of a militarized prisoner management system during the American Revolution. During Ethan Allen’s 1775 Canadian campaign, American commanders in the Continental Army sent prisoners of war captured in British-held forts to be managed by state and local authorities in Pennsylvania, New York, and Connecticut. Between 1775-1777, state assemblies and local committees of safety managed military prisoners on an ad-hoc basis with little guidance from the Continental Congress.

Starting in 1777, Congress began centralizing prisoner management efforts in the Continental Army. George Washington selected Elias Boudiont, a New Jersey lawyer, to serve as the nation’s first Commissary General of Prisoners. Boudinot appointed deputies with the rank of major to serve in various confinement centers for prisoners, including Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Rutland, Massachusetts, and Charlottesville, Virginia. Boudinot managed the movement and exchange of prisoners, as well as their care in various host towns. In a 1777 letter, Boudinot complained to Congressman Elbridge Gerry about two prisoners who “th’o treated in the politest manner by Gen’l Washington behaved so as to give general offence where they were quarter’d… I sent them to Philadelphia, where they behaved with great insolence to Gen’l Gates- after they left Phil’a & went to Lancaster. I had frequent complaints of their ill Behaviour….” Boudinot ended his letter by talking about his hopes for a rapid exchange of the troublemakers.

Though Congress attempted to vest authority over prisoners in the Continental Army, questions persisted about whether civil or military authorities had final say regarding their care. As the war continued, the problem became more complex as military commanders attempted to assert their own authority over that of deputy commissaries under Boudinot and his successors. In a letter from Brigadier General Moses Hazen to Major General Benjamin Lincoln, Hazen lamented a “State of Confusion” in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Hazen’s 2nd Canadian Regiment was stationed in town to guard prisoners, but problems arose between the commander and the deputy commissaries. “The assistant Commissary of Prisoners think [themselves] Independ of me- I have not been able to obtain from Col. Gibson at York Town a Report of the muster of the prisoners of war for the month of may last.” Hazen alleged that the commissaries failed to do their duties relative to the care of the prisoners, but that “every loss of prisoners… unjust is Charged on the Regiment.”

Issues of authority over military prisoners persisted until the end of the war. Though Congress attempted to militarize prisoner management, state and local governments continued to wield authority in the exchange, transportation, and guarding of military prisoners. Complicating matters, the staff department dedicated to prisoner management faced opposition from Continental Army commanders. The 1783 Treaty of Paris liberated those prisoners who did not escape, die, or return home via exchange in the course of the war. Though imperfect, the militarization of wartime civilian support services including prisoner management challenges the idea that the war acted as the staging ground for the “civil over military” ideal in American history.