Women in the American Revolution

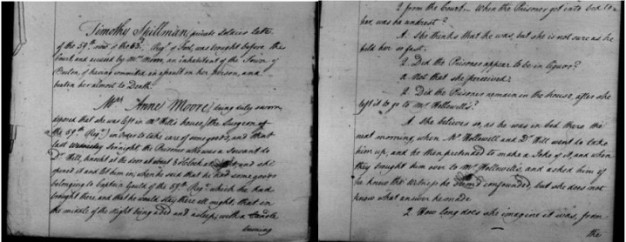

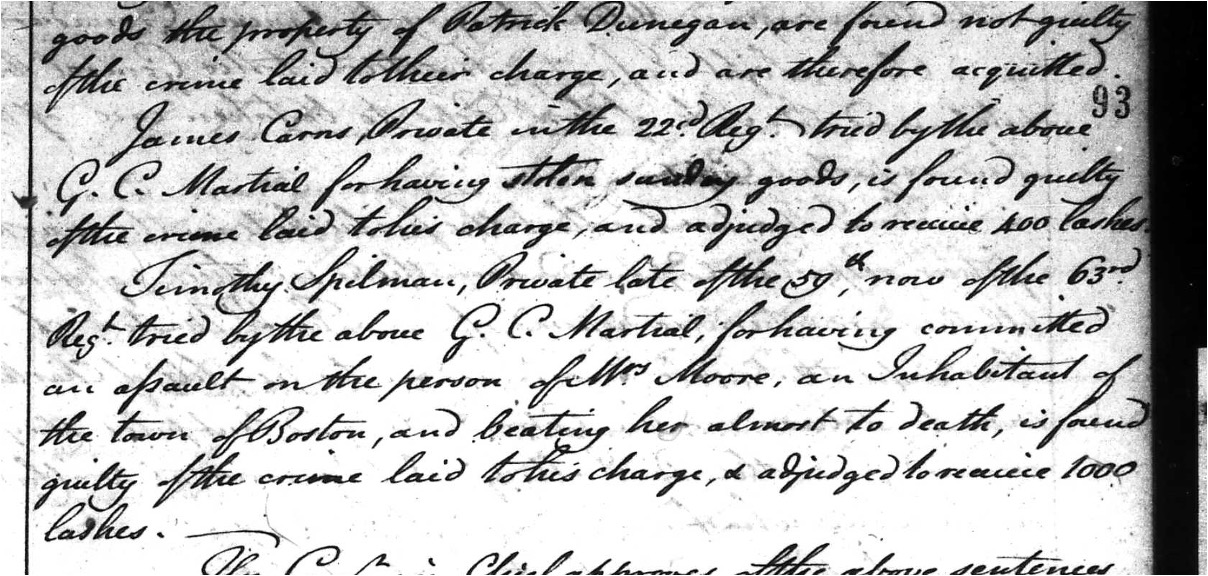

Header Image: Judge Advocate General's Office: Courts Martial Proceedings and Board of General Officers' Minutes [WO 71], General Court Martial of Timothy Spillman, Boston, Massachusetts, 12-28 December 1775, WO 71/82, 250, 251, Reel 8, Mss.DLAR.Film.675. APS..

In late December 1775, Anne Moore packed up her employer’s home and office, preparing to move with the British 59th Regiment’s physician from occupied Boston to London. By the end of the evening, Moore would need medical care. The sun had long since set when her colleague, Private Timothy Spillman, arrived with various items to include alongside the doctor’s remedies and medical supplies. Moore offered Private Spillman rum and water to warm up from the bitter cold before she retired to her bedroom upstairs. In the middle of the night, Private Spillman extinguished the candle next to her bed, knocked her unconscious against the windowpane, and attempted to sexually assault her. When she came to, she ran into the cold and to her neighbors in search of help.

Private Spillman was brought before a British General Court-Martial for nearly killing Moore. In his deposition, Private Spillman claimed he did not know Moore and she must have fallen down the stairs. From her deposition, along with her stark bruises on her face and neck, Private Spillman was sentenced to one thousand lashes for assault. However, the verdict reached by the thirteen men made no reference to the sexual nature of the attack. Eighteenth-century notions of consent—she had offered him a drink—precluded such a verdict.

Among the rows and rows of microfilm reels at the David Center for the the American Revolution at the American Philosophical Society are the “Courts Martial Proceedings and Board of General Officers' Minutes.” From Gibraltar to Boston, these administrative records detail punishments meted out for infractions ranging from desertion and theft to mutiny and assault. Court martial records provide glimpses into soldiers’ violent behavior and conduct against local women. These instances of assault were not new to colonial women. Rather, these documents contain testimony from women across the spectrum of unfreedom, often omitted in the archive. Moore’s recorded experience is emblematic of many women assaulted at the hands of both British and Continental Army soldiers. Even when women were not victims, court martials included the testimony and, therefore, their perspective. Maintaining order within the ranks required interviewing witnesses regardless of status, race, and political affiliation.

Moore’s deposition serves as an example to illustrate how to examine these accounts. Read alongside other records in the collection, such as the American Rebellion: Extracts of Entry Books with Orders Given to the British Army in America (Mss.DLAR.Film.19) and the Early American Orderly Books (Mss.DLAR.Film.42), highlights the reverberations of war on the home front rather than on the battlefield. As a David Center for the American Revolution Short-Term Fellow, I examined these accounts as part of my larger project on the medical strategies utilized by dispossessed women to address everyday violence during the Revolutionary era. Perspectives from local women are crucial for exploring women’s communities of care or resistance against quotidian violence inflicted by mothers, fathers, husbands, enslavers, soldiers, and town officials.