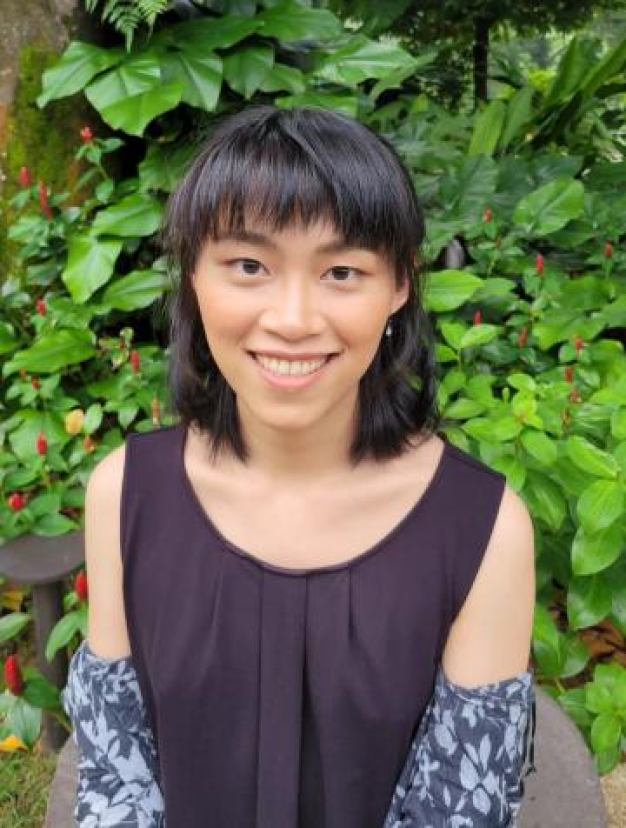

Featured Fellow: Yingchen Kwok (2024-2025 Mellon Foundation Short-Term Research Fellow

The Library & Museum at the American Philosophical Society supports a diverse community of scholars working on a wide-range of projects in fields including early American history, history of science and technology, and Native American and Indigenous Studies, among others. Additional information about our fellowship programming and other funding opportunities can be found here.

Briefly describe your research project and the collections used while working at the APS.

My research examines how biologists used gender norms to structure their investigation of sexual reproduction as a mechanism for producing hereditary variation. Gender norms reflect an ideal relationship between order and variation, entrapping women and men within a rigid sexual division of labor while celebrating that structure as an invaluable source of pluralism. This made them instrumental in appraising hereditary variation as a source of progress rather than a threat to social order. My work spans three major historiographical periods: late 19th-century developments in evolutionary theory and cytology, the founding of classical genetics in the early 20th century, and scientific debates about race after World War Two. By employing queer and trans theoretical analysis, I seek to understand how contemporary valuations of cultural and biological diversity remain rooted in a historical paradigm that privileges the experiences of cisheterosexual people.

What collection(s) did you use while working at the APS?

The primary collections I examined at the APS were the papers of Theodosius Dobzhansky, L. C. Dunn, H. S. Jennings, and Raymond Pearl. However, there were plenty of secondary collections as well, such as the papers of Milislav Demerec, Curt Stern, Richard Lewontin, Sewall Wright, the Berkeley Department of Genetics, the American Eugenics Society, and the Genetics Society of America. I also utilized the finding aid to locate correspondence with some of my key actors in other miscellaneous collections.

What’s the most interesting or most exciting thing you found in the collections?

The Berkeley Department of Genetics collection features an intriguing exchange between the plant geneticists G. H. Shull and E. B. Babcock. In it, Shull argues that the stamens and pistils of flowering plants should be considered their “male” and “female” reproductive organs, going against the prevailing view among botanists of his time. Far from being a simple technical debate, the question of what stamens and pistils really are is a deeply philosophical one about where a biological individual begins and ends. All plants alternate between sexually reproducing (gametophyte) and asexually reproducing (sporophyte) generations. In flowering plants, the entire visible plant is the asexual generation. Stamens and pistils do not produce gametes, but spores that develop into the gamete-producing sexual generation entirely within the plant’s “ovary.”

Shull contends that the sporophyte generation of a flowering plant is no different from the somatic cells of an animal—both comprise diploid cells that reproduce asexually. He goes on to reason that if stamens and pistils cannot be considered sex organs because the sporophyte and gametophyte generations are separate organisms, then animal genitalia cannot be considered sex organs either! This is an example of reductio ad absurdum reasoning. Of course, it is impossible for us to envision animal bodies as comprised of separate asexually and sexually reproducing generations. There is only one sexual generation, and our asexually reproducing bodies are merely a somatic extension of it. If this holds true—and surely it must—then we must accept by analogy that stamens and pistils are the sex organs of flowering plants. But I think we can take Shull’s argument to demonstrate the exact opposite: that our bodies are stranger than we realize.

This discussion also alludes to the broader role of plants in the history of sex, heredity, and reproduction. The Western world has long viewed flowers as symbols of womanhood, as they seemingly align with a paradoxical cis-hetero-patriarchal ideal of femininity that demands both fertility and chastity. Flowers evoke the abundance of nature while avoiding direct associations with sexual intercourse. However, plants are remarkably difficult to fit into such rigid gender norms, not least because they challenge conventional notions of biological individuality. Questions about plant sexuality can seem threatening because they often implicitly address questions about female sexuality.

Finally, this exchange alludes to the understated role of ideas about biological sex in bridging the paradigms of late 19th-century morphology and the ascendant genetics of the 20th century. It is a fantastic resource for helping me chart the transition from one period to the other in my dissertation.

Yingchen Kwok is a PhD candidate at the University of Pennsylvania. Her dissertation examines how biologists drew on gender norms to structure their investigation of sexual reproduction as a mechanism for producing hereditary variation between the 1880s and 1950s. She argues that this legacy is essential to understanding the emergence of diversity as a biological concept after World War Two and its continued enmeshment within a cisheternormative logic of sexual difference. She is also an admin of Trans PhD Network, a Facebook networking and support group for transgender graduate and early career scholars.