“The Life Story of a People:” Ella Cara Deloria and the Lumbee

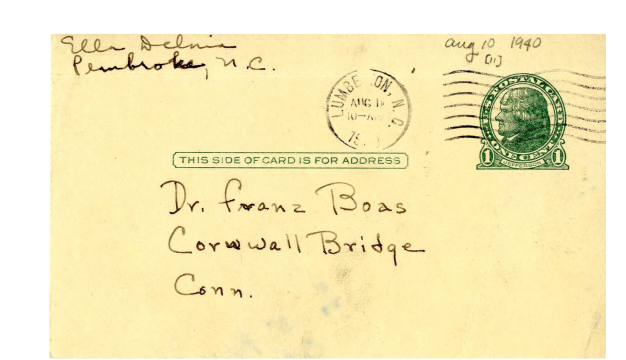

Header Image: “Deloria, Ella C..: To Boas. 1940 Aug. 11.” Franz Boas Papers. American Philosophical Society. Mss.B.B61

In the summer of 1940, Ella Cara Deloria, a Dakota anthropologist and ethnographer, was hired by the Office of Indian Affairs and the Farm Security Administration (FSA) to write and produce a pageant that would inspire racial pride and unity amongst the Indians of Robeson County, North Carolina, who are now known as the Lumbee. While Deloria is well known for her work documenting Dakota language and cultural traditions, her work amongst the Lumbee is more obscure. The Franz Boas Collection at the American Philosophical Society Library contains correspondence between Deloria and her mentor, Franz Boas, that document her experience producing this pageant.

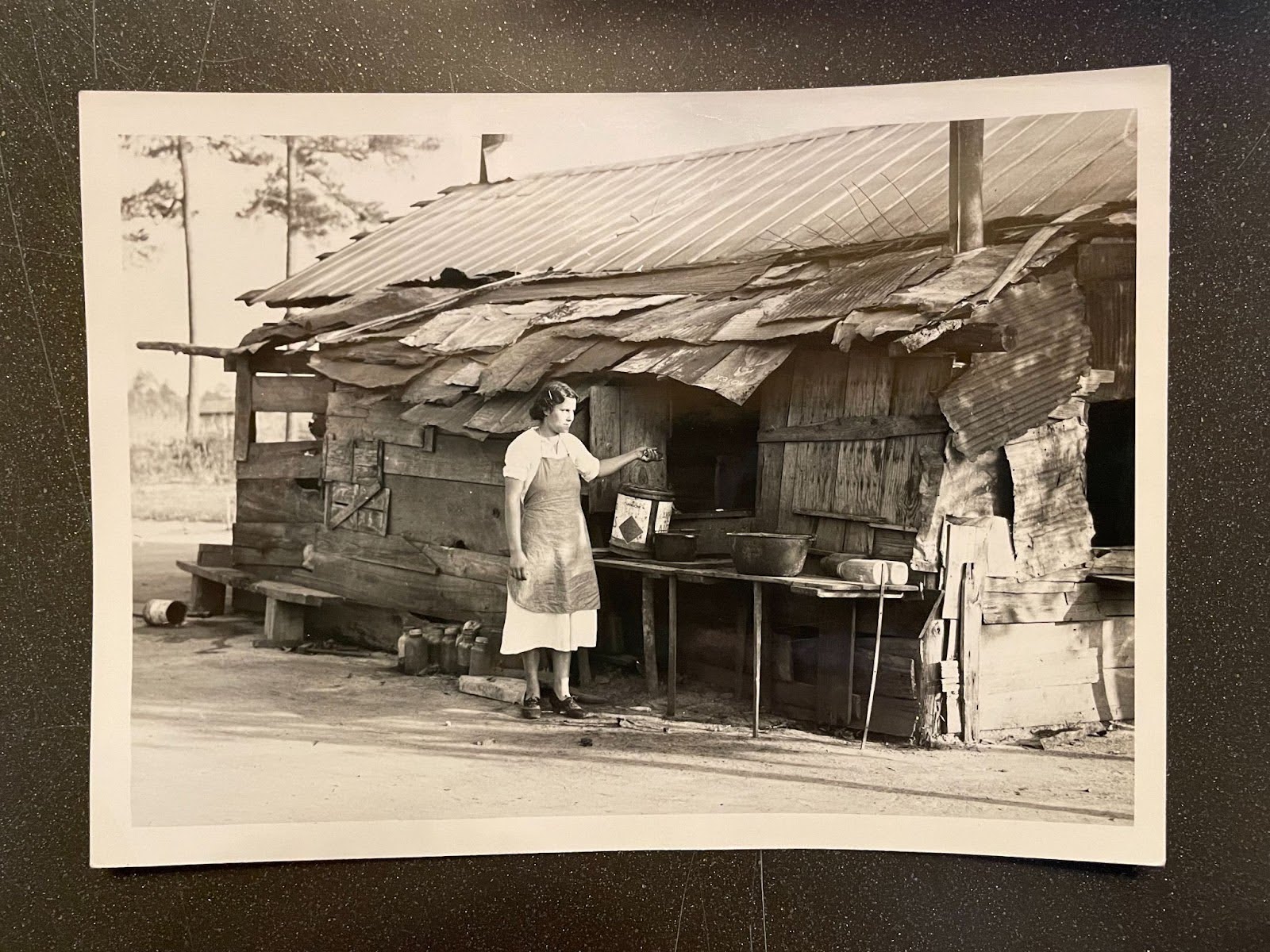

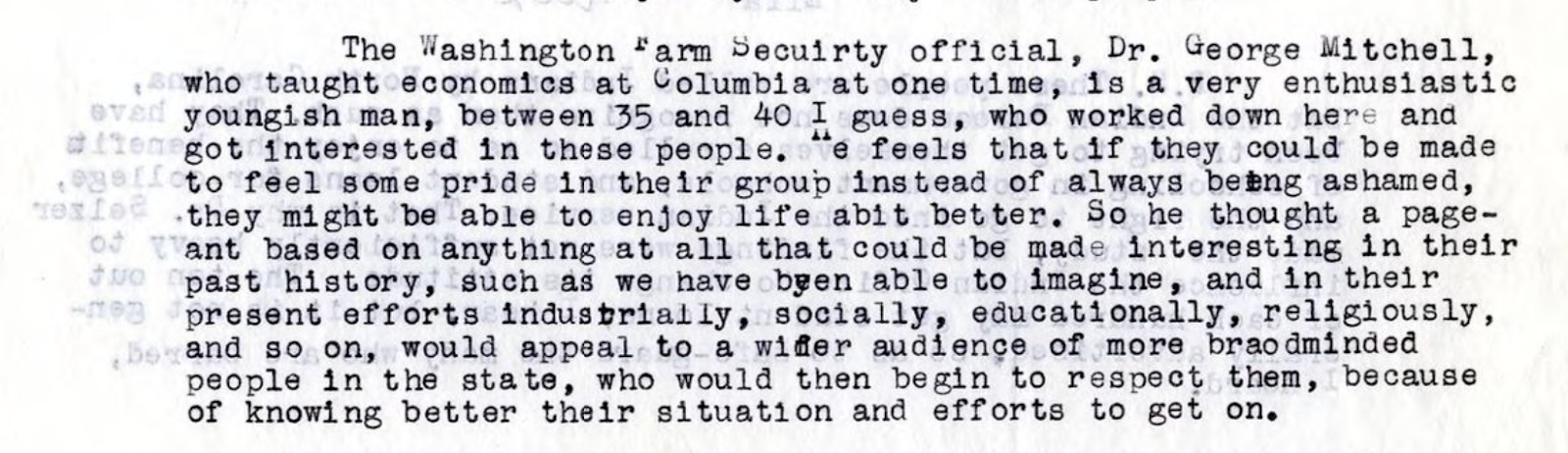

During the Great Depression, a number of Lumbee families experiencing economic strife received assistance from the FSA, a New Deal initiative created to alleviate rural poverty by resettling families onto more productive farms with more adequate housing. While the FSA was successful in improving the material aspects of Indian families' lives, administrator George Mitchell noted that segregation and the rampant racial prejudice held by neighboring whites against Indians was a hindrance to the FSA’s goals of improving their overall quality of life. As a means of remedying this, Mitchell hired Deloria to write a community pageant themed around Indian progress through history that would combat some of this racial prejudice.

“Pembroke Farms FSA - N.C.” National Archives and Records Administration, RG 75, Entry 121, Box 322.

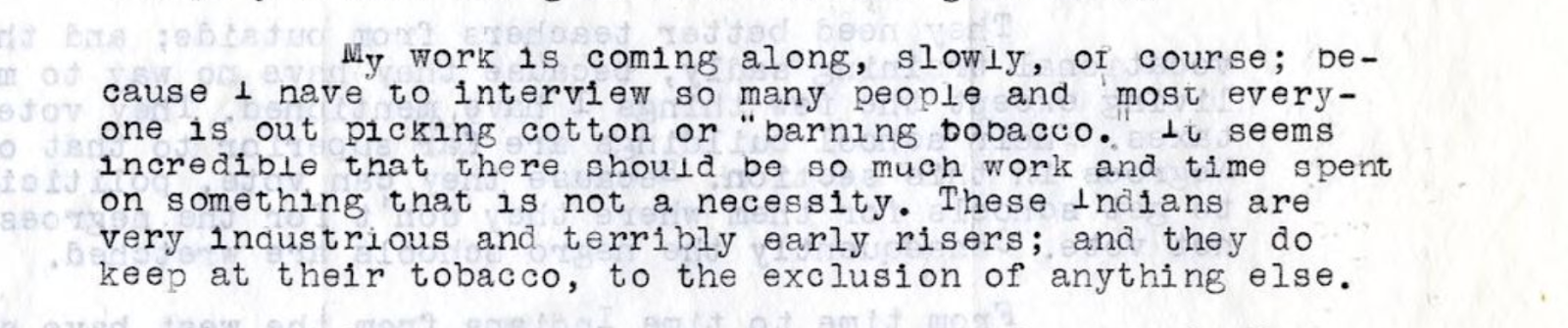

“Deloria, Ella C..: To Boas. 1940 Aug. 7.” Franz Boas Papers. American Philosophical Society. Mss.B.B61

While Deloria was considered an expert on Indigenous cultures, this might have been the first time she had ever heard of the Indians of Robeson County. In order to gain insight into these peoples’ history, Deloria familiarized herself with the few materials that had been written about Robeson County’s Indians. These materials consisted of early 20th century anthropological studies, which concluded that the Indians of Robeson county were suffering from a loss of culture because of the lack of a surviving Indigenous language. Other materials consisted of eugenic studies that called the Indians of Robeson County a racially mixed people whose Indian blood had been compromised through intermarrriage. When Deloria first arrived in North Carolina, she wrote to Boas with a sense of skepticism that stemmed from these studies about the Robeson County Indians, doubting that she would be able to find enough historic and cultural source material to come up with content for a pageant based on the community’s history. While early 20th century academic studies concluded that the Indians of Robeson County could not be authentic Indians, Deloria knew that she needed to read these sources with a critical eye and held them at a distance when conducting her field work.

As Deloria built relationships with Lumbee people and took time to listen to their stories about the past and present, she privileged the knowledge that came from Lumbee people themselves rather than materials written about them by outsiders. For example, Deloria initially questioned why these Indians were so committed to growing their cotton and tobacco but came to realize that Lumbees valued agriculture because it granted many the economic means to survive and remain in their North Carolina homelands. Deloria also noted that since her arrival in Robeson County, she attended two different church services every Sunday–not out of religious fervor, but to be fully immersed into the spiritual, social, and political hubs of each Lumbee community.

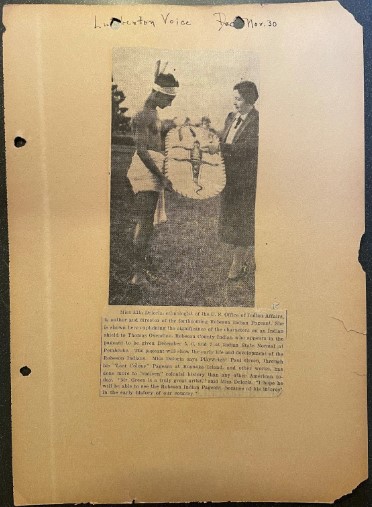

Through the pageant script, Deloria wrote a history of Lumbee progress throughout their history which was centered around community values of agriculture, labor, education, religion, and war. “The Life-Story of a People” premiered on December 5, 1940 and featured an all-Lumbee cast with costumes and props designed by Deloria’s sister, Mary Sully. The two hour performance ran for three consecutive days, each to a sold out crowd. Viewers came from fifteen states and special guests included D’Arcy McNickle, Mrs. Paul Green (wife of Paul Green, playwright of “The Lost Colony”), and a delegation from the Catawba Nation of South Carolina. According to Deloria, members of the Lumbee community, and newspaper coverage, the play was successful in fostering a sense of community pride and unity. Though the pageant was not free from stereotypical elements, like western-style costuming and primitive portrayals of pre-Columbian life, which are seen as problematic today, Lumbees celebrated the pageant because it gave them a platform to celebrate their shared identity as a people.

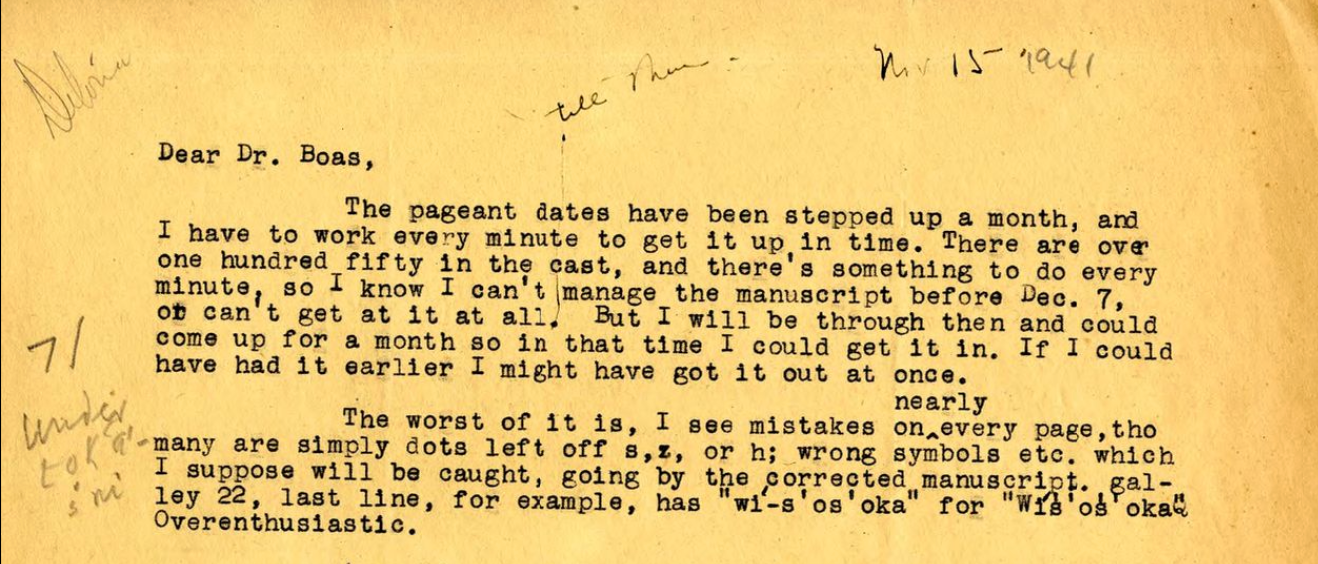

The pageant was so successful that members of the community invited Deloria to come back the following year, with the intention of making it an annual event. Despite fulfilling her contract with the FSA, who originally hired her, Deloria returned on her own volition in 1941. Working directly for the community this time, Deloria produced the pageant again, even putting her work on the Dakota language aside to prioritize helping the Lumbees with their pageant. Based on Deloria’s writings and CV, it is clear that the “The Life Story of a People” was a passion project for her and that she was very proud of it. When Deloria concluded her work in Robeson County, she entrusted her copy of the pageant with a Lumbee family, who promised to keep it safe. After Deloria’s death, her nephew, Vine Jr., traveled to Pembroke to try to locate a copy of the pageant, but the family refused to give it to him because they feared it would be lost or stolen by outsiders.

“Deloria, Ella C.: To Boas. 1941 Nov. 15.” Franz Boas Papers. American Philosophical Society. Mss.B.B61

While Deloria is now remembered for her exemplary scholarly achievements, much of her work was underappreciated during her lifetime. Deloria’s letters to Boas reveal that she was underpaid for her labor and a lack of finances prevented her from protecting her work. Deloria’s nephew, Vine Jr., noted that Ella had two trunks full of notes from her time working in Robeson County, which she had to throw away and sell because she could not afford to have them stored or transported. Despite this tragic loss of material, Deloria and her work lived on in Lumbee public memory. Despite not having an actual copy of the script, Deloria’s pageant work was cited in the 1987 petition for Lumbee federal recognition. In fact, Vine Deloria, Jr., noted that “Ella was fascinated with the Lumbees and … if she had lived to give testimony on their behalf when they were seeking federal recognition she would have been a powerful witness.”

Though Deloria never had this opportunity, piecing together fragments of her work show that she grew to admire the fact that Lumbee people continued to exist as Indians without recognition or assistance from the federal government. Given this present political moment, where the Lumbee path to full federal recognition is still unclear, Deloria’s work reminds us that the Lumbee will continue to exist through a constant determination to survive.

Works Cited & Further Reading

- Deloria, Ella C. “Deloria, Ella C.: To Boas. 1940 Aug. 11.” Franz Boas Papers, American Philosophical Society. https://diglib.amphilsoc.org/islandora/object/text:36580.

- Deloria, Ella C. “Deloria, Ella C.: To Boas. 1940 Aug. 7.” Franz Boas Papers, American Philosophical Society. https://diglib.amphilsoc.org/islandora/object/text:36578.

- Deloria, Ella C. “Deloria, Ella C.: To Boas. 1940 Dec. 26.” Franz Boas Papers, American Philosophical Society. https://diglib.amphilsoc.org/islandora/object/text:36584.

- Deloria, Ella C. “Deloria, Ella C.: To Boas. 1940 July 18.” Franz Boas Papers, American Philosophical Society. https://diglib.amphilsoc.org/islandora/object/text:36593.

- Deloria, Ella C. “Deloria, Ella C.: To Boas. 1940 Sept. 9.” Franz Boas Papers, American Philosophical Society. https://diglib.amphilsoc.org/islandora/object/text:36588.

- Deloria, Ella C. “Deloria, Ella C.: To Boas. 1941 Nov. 15.” Franz Boas Papers, American Philosophical Society. https://diglib.amphilsoc.org/islandora/object/text:36582.

- Deloria, Ella Cara. Resumés. Personal and Professional Papers, Ella Deloria Archive, Dakota Indian Foundation. https://indigenousknowledge.indiana.edu/resources/deloria/browse.php?action=viewpage&id=267.

- Deloria, Ella Cara. The Life Story of a People. Personal and Professional Papers, Ella Deloria Archive, Dakota Indian Foundation. https://indigenousknowledge.indiana.edu/resources/deloria/browse.php?action=viewpage&id=138.

- Deloria, Vine Jr. Introduction to Speaking of Indians, by Ella Cara Deloria. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998).

- Gardner, Susan. “‘Weaving an Epic Story’: Ella Cara Deloria’s Pageant for the Indians of Robeson County, North Carolina, 1940-1941.” The Mississippi Quarterly. 60, no. 1 (2006): 33-58.

- Lowery, Malinda Maynor. Lumbee Indians in the Jim Crow South: Race, Identity, And the Making of a Nation (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010).

- National Archives and Records Administration. Record Group 75, Bureau of Indian Affairs. Central Classified Files, Box 322.