The Gouverneur Morris Papers: From the Chaos of the French Revolution to the Quiet Reading Room on Library Street

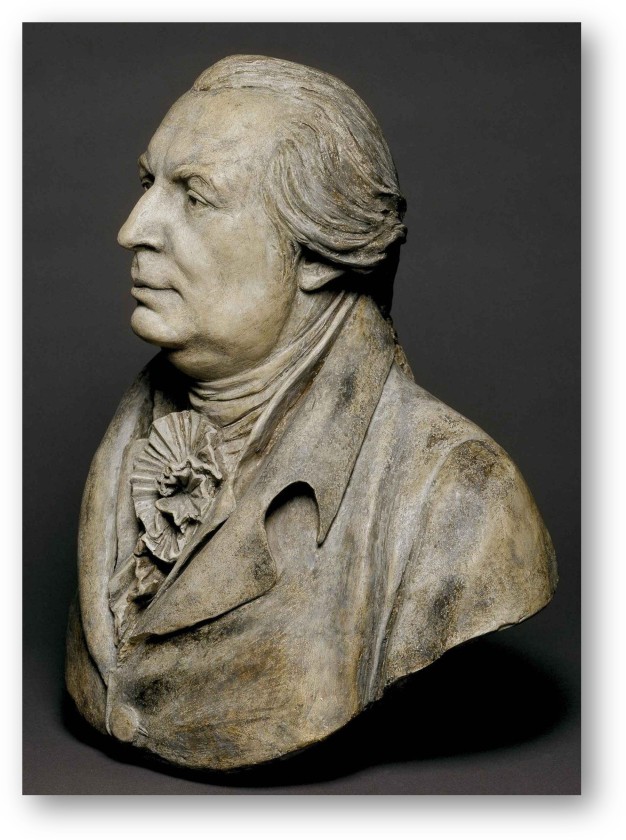

Bust of Gouverneur Morris, 1792, by Jean Antoine Houdon

The American Philosophical Society’s collection of Gouverneur Morris papers is a significant one. The opportunity to study them earlier this year, thanks to the Society’s Friends of the APS Fellowship, yielded many documents that helped expand this Founding Father’s life story and gave our project some unexpected and exciting material. A document relating to his time in France during the French Revolution (he succeeded Thomas Jefferson as our minister in Paris) is an excellent example.

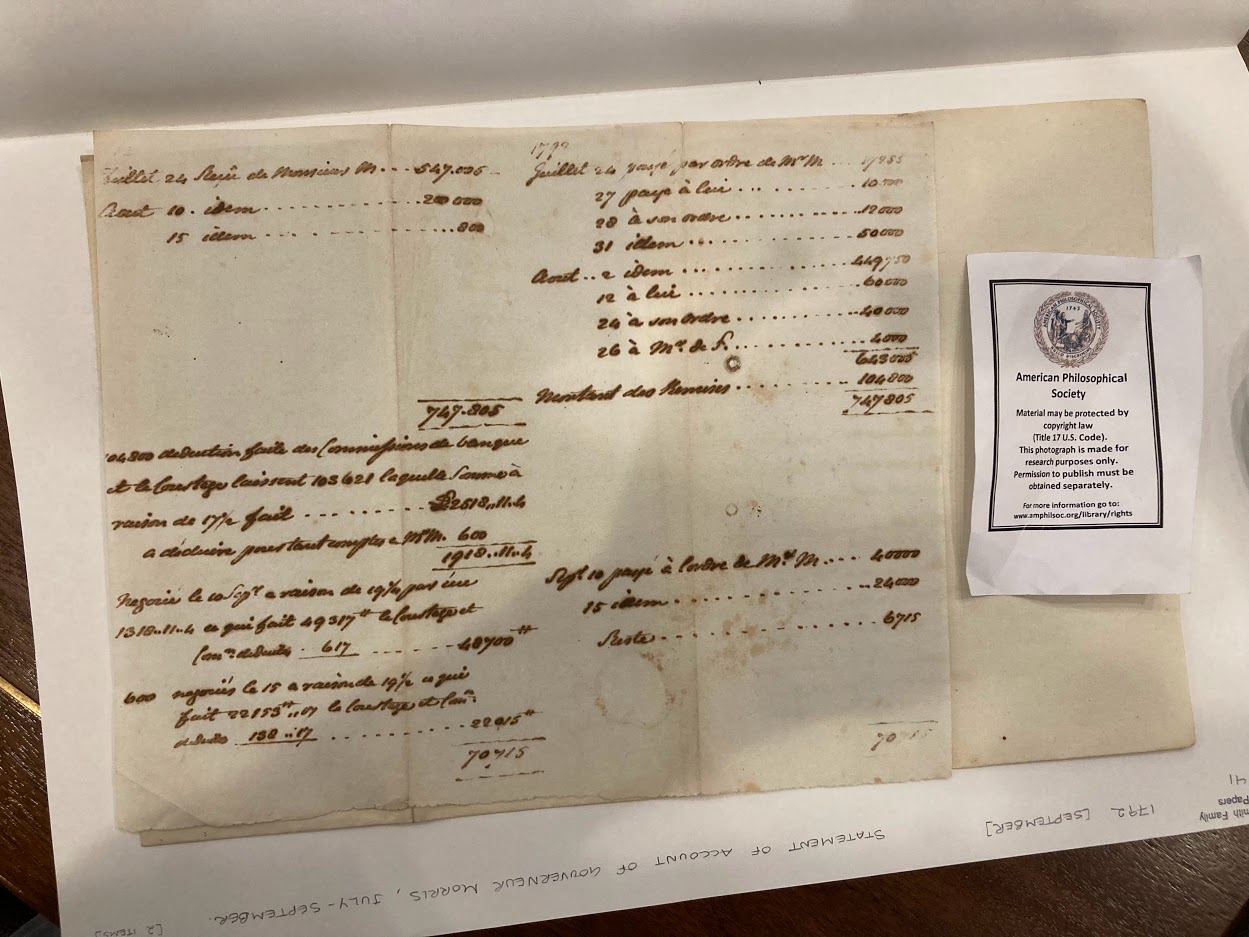

Labeled simply as a “statement of account of Gouverneur Morris, July-September 1792,” the paper is a record of the money Morris agreed to receive from Louis XVI to raise a counter-revolutionary force when it became clear that the monarchy was in danger of violent overthrow. This was a remarkable episode—while he was U.S. minister, Morris conspired with some of Louis’s loyal counselors to try to save the monarchy and help the royal family escape. Some years later, in Vienna, Morris prepared a memorandum for Madame Royale, the only surviving child of Louis and Marie Antoinette, giving a summary of the amounts received and disbursed. The memorandum corresponds to the amounts in this rough document, though the document contains more detail on both, including dates. The last large receipt was recorded on the very day the palace was stormed and the King fell, August 10, 1792.

Another group of items that I was delighted to find relate to the much-admired Marquis de Lafayette, whom Morris knew during the American Revolution and saw again in France. The letters came from Morris’s close friend and business partner, James LeRay de Chaumont. They discuss LeRay’s efforts to obtain repayment of an enormous personal loan Morris made to Lafayette’s wife at her request, to cover their “debts of honor” after the Marquis—whose fall from leader of the Revolution to being considered a traitor had been swift, just as Morris had predicted— fled France and was imprisoned by the Austrians. Our research for Morris’s later diaries (1799-1816) originally led us to the tentative conclusion that Morris had never been repaid. These letters confirm it. His later financial difficulties were considerably exacerbated by this default.

It was acknowledged by her family and others that Morris saved Mme. de Lafayette from the guillotine during the Great Terror, and his diaries show that his efforts led to the Austrian emperor’s decision to release the Marquis in 1797. A letter from LeRay, who met with Mme. de Lafayette in Paris more than once after she and her husband returned to France and were restored to their estates, confirmed what I could only infer from Morris’s letters: that Madame de Lafayette (who had never forgiven Morris for speaking truth to her husband in the early days of the Revolution) seemed outraged that Morris had the nerve to request repayment—he had waited for several years after Lafayette’s release for them to act—and accused him of trying to profit from the loan. She at one point grudgingly offered to pay in depreciated (grossly depreciated) value; then moved to offering only interest and nothing else. In the end, they paid him nothing. On August 10, 1803, LeRay, now in New York, wrote Morris of her last arrogant refusal:

It says: “Curse the vile conduct – Shame upon them…mon sang bouilloune [my blood boils].” LeRay knew what few others did: how much Morris had done for the Lafayettes. These letters are significant because of how they reflect on both Morris, so often deprecated to this day, and on the always-lionized Lafayette.

We have much reading and transcribing to do of APS material, and expect to find many more gems relating to Morris’s extraordinary life.