Expanding Animal Knowledge

in the Age of Natural History Case Three

By the nineteenth century, a golden age of science, an age of natural history was well underway. With the influence of the Enlightenment, the scientific revolution, and in particular the work of Swedish naturalist Carl von Linne, there was a growing urge to rationally explain the natural world. In Systema Naturae (first published in 1735 and then expanded over the following decades), Linne created a comprehensive taxonomy to classify all known plants and animals based upon shared physical characteristics. At the time, it was thought there was a fixed number of species on Earth, and that, through effort, all of nature could be cataloged and studied. There was a very real rush to explore, discover, and describe nature. The Lewis and Clark Expedition was not an isolated endeavor. This page explores various attempts to expand animal knowledge in the age of natural history.

In 1808-1814, Alexander Wilson produced the nine-volume American Ornithology, a stunning masterpiece of natural history. He portrayed vibrant American birds such as the cardinal and scarlet tanager with "well authenticated facts deduced from careful observation, precise descriptions, and faithfully portrayed representations drawn from living nature." Melding art with science, Wilson's work set the standard for illustrated works on natural history.

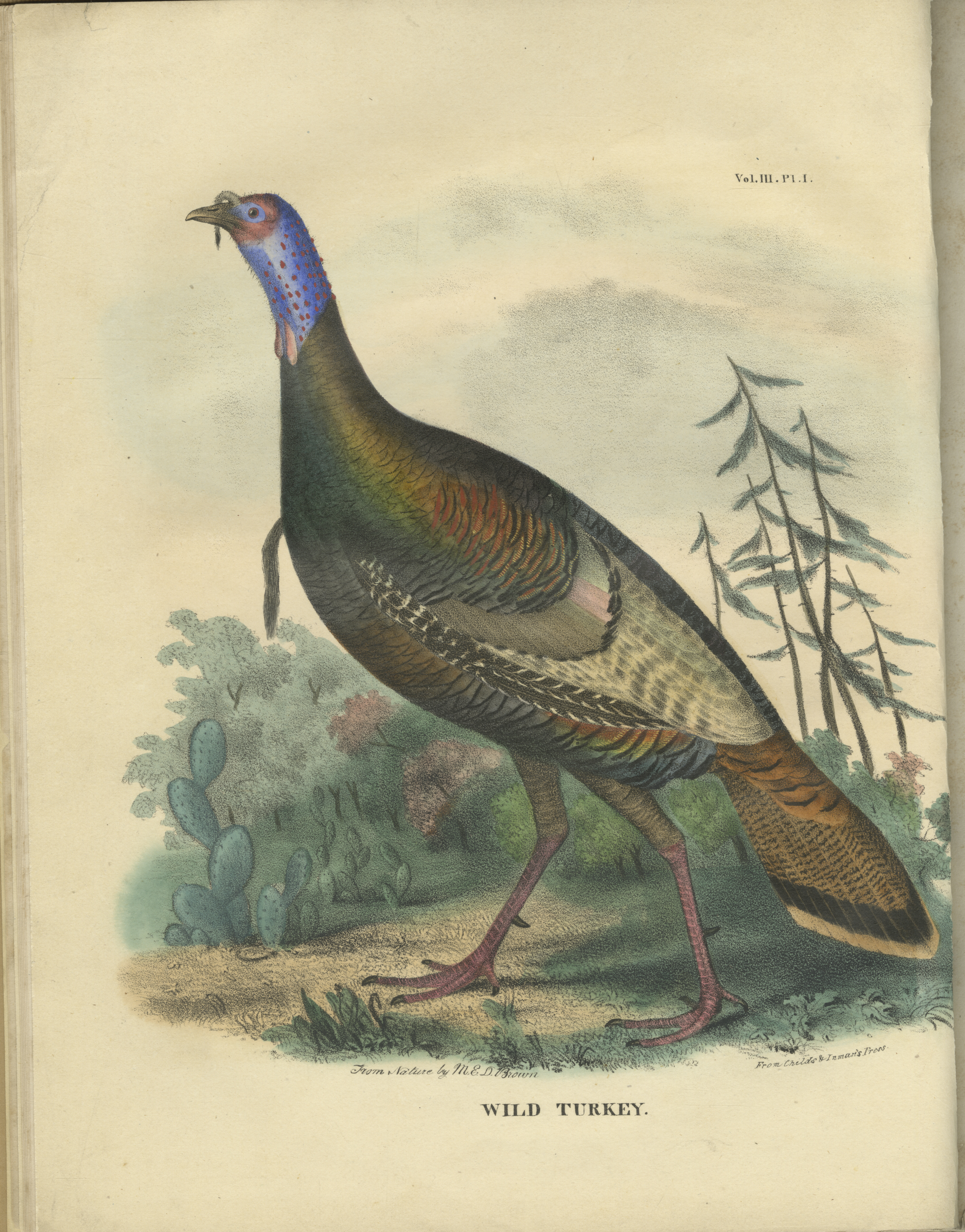

Lithographer M.E.D. Brown created an image of the Wild Turkey for the Cabinet of Natural History (1833), the first colored American sporting book. Benjamin Franklin, founding father of the APS, would no doubt have warned hunters of the prowess of the turkey. The bird, "though a little vain and silly, [was] a bird of courage, which would not hesitate to attack a Grenadier of the British Guards" [Benjamin Franklin to daughter Sarah Franklin Bache, 1784].

John James Audubon, best known for his massive elephant folio Birds of America (1827-1838), of which the APS was an original subscriber, produced other noteworthy works of natural history. Partnering with John Bachman, he published The Quadrupeds of North America (1854). This particular work, at a more manageable size for the reading public, featured brilliantly-colored mammals, such as the groundhog.

Scottish naturalist William Jardine produced the 40-volume Naturalist's Library, a set popular with the British public. The third volume, published in 1834, was The Natural History of Felinae, covering the history of cats. Pictured here is the Puma or American Lion, which once appeared from California to Pennsylvania.

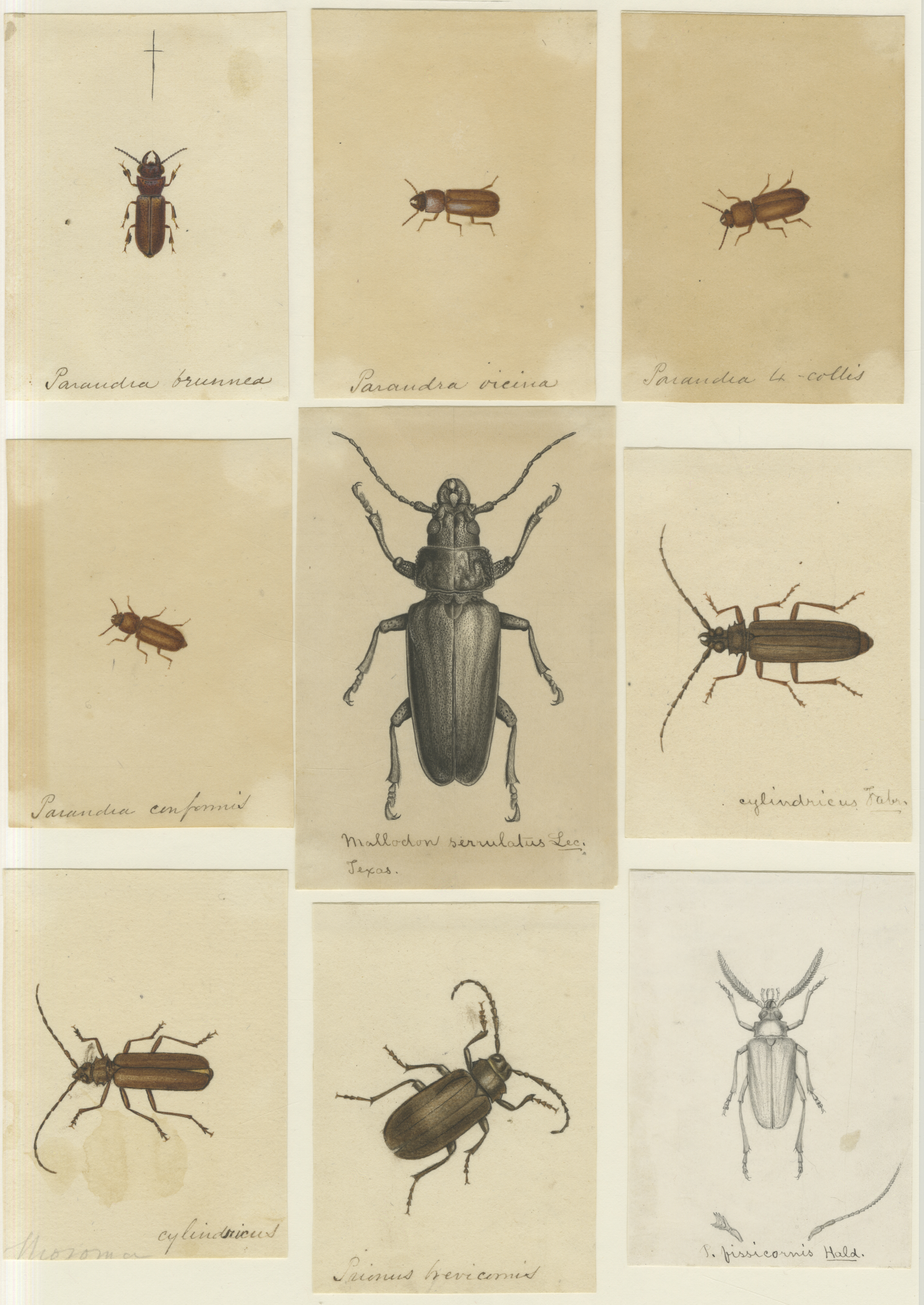

It is now time to turn to insects, which make up approximately 80% of the species on Earth. Early American naturalists shied away from cataloging insects, and relied heavily upon their European counterparts for describing the small creatures. Entomologist John Lawrence LeConte sought to remedy this situation, dedicating himself to classifying insects, the beetle in particular. In 1883, he published a taxonomy which classified 11,000 beetles. The beetle images here, drawn by LeConte himself, are testimony to his work.

The next item is Englishman John Benbow's Bee Book (1846-1854), a meticulously illustrated guide to beekeeping, filled with amusing anecdotes. Benbow notes in his tiny manuscript that beekeeping can be a painstaking hobby--because of the beestings!

The last three images are from a later era, the 1930s, and represent the increasing fascination with animals as pets. The three images of tropical fish, created by German illustrator Fritz Mayer, come from the papers of William Innes. Innes is best known for the work Exotic Aquarium Fishes (1935), for which these images were created.

Image Gallery

-

Cardinal Grosbeak

Alexander Wilson (1766-1813). American Ornithology, Cardinal grosbeak, page 38, 1810. (598.2 W69, vol. 2)

Alexander Wilson had a particular fondness for the cardinal: "The sprightly figure and gaudy plumage of the Red-Bird, his vivacity, strength of voice, and actual variety of note...will always make him a favorite."

Turkey

Mannevillette Elihu Dearing Brown (1810-1896). Cabinet of Natural History and American Rural Sports, Wild Turkey, page 13, 1833. (505 C11, vol. 3)

Benjamin Franklin thought so much of the turkey that he opined that it should be the national bird of the United States:

For my own part I wish the Bald Eagle had not been chosen as the Representative of our Country. He is a Bird of bad moral Character. He does not get his Living honestly. You may have seen him perch’d on some dead Tree near the River, where, too lazy to fish for himself, he watches the Labour of the Fishing Hawk; and when that diligent Bird has at length taken a Fish, and is bearing it to his Nest for the Support of his Mate and young Ones, the Bald Eagle pursues him and takes it from him. With all this Injustice, he is never in good Case but like those among Men who live by Sharping and Robbing he is generally poor and often very lousy. Besides he is a rank Coward: The little King Bird not bigger than a Sparrow attacks him boldly and drives him out of the District...For in Truth the Turkey is in Comparison a much more respectable Bird, and withal a true original Native of America. Eagles have been found in all Countries, but the Turkey was peculiar to ours...He is besides, tho’ a little vain and silly, a Bird of Courage, and would not hesitate to attack a Grenadier of the British Guards who should presume to invade his Farm Yard with a red Coat on. [Benjamin Franklin to daughter Sarah Franklin Bache, 26 January 1784]

Groundhog

John James Audubon (1785-1851) & John Bachman (1790-1874), The Quadrupeds of North America, Groundhog, 1854. (599 Au2v.q, vol. 1)

Groundhogs typically hibernate from October to March. Audubon and Bachman included an amusing anecdote from Daniel Wadsworth to demonstrate this. Wadsworth kept a groundhog as a pet and allowed it to live inside his house. He became puzzled by the animal’s lethargy:

It was inanimate, and as round as a ball, its nose being buried as it were in the lower part of its abdomen, and covered by its tail; it was rolled over the carpet many times, but without effecting any apparent change in its lethargic condition; and being desirous to push the experiment as far as in my power, I laid it close to the fire, and having ordered my dog to lay down by it, placed the Wood-Chuck in the dog’s lap. In about half an hour, my pet slowly unrolled itself, raised its nose from the carpet, looked around for a few minutes, and then slowly crawled away...I...placed [it] again in its box, where it went to sleep, as soundly as ever, until spring made its appearance.

-

Puma

William Jardine (1800-1874). The Natural History of the Felinae, Puma or American Lion, 1834. (590 J28N vol. 2)

Jardine noted that the Puma has an extensive range over the American continents. In the south, it has been known to stalk cattle, for which gauchos are continually battling to protect their herds. In the north, it lives primarily on deer, "upon which it is said sometimes to drop from a tree, which it had ascended to watch their path."

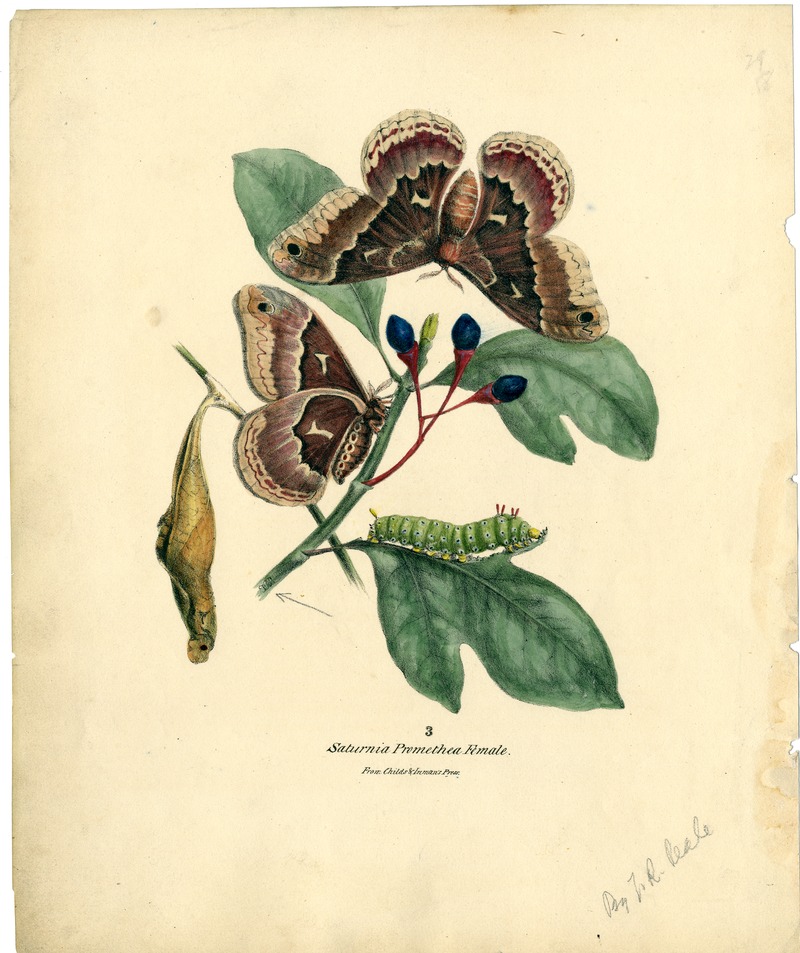

Moths

TR Peale (1799-1885). Moths: Saturnia Promethae, [1833]. (Mss.B.P31.15d, no. 233d)

The original of this image is a colored lithograph thought to have been created by Peale for his planned 1833 work, Lepidoptera Americana. Unfortunately, Peale never finished the project.

Beetles

John LeConte (1825-1883). Entomological Drawings, Beetles (vol. 1, pg. 28), n.d. (Mss.595.7 L493)

The beetles depicted here represent just one page--nine images--of an impressively ambitious project. A founding member of the American Entomological Society, LeConte attempted to compile a comprehensive catalog of insects. He created over three thousand images of Coleoptera (beetles), Diptera (flies), Hemiptera ("true bugs"), Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies), Hymenoptera (bees), Araneina (spiders), and Myriapoda (millipedes and centipedes). APS houses the papers of LeConte.

-

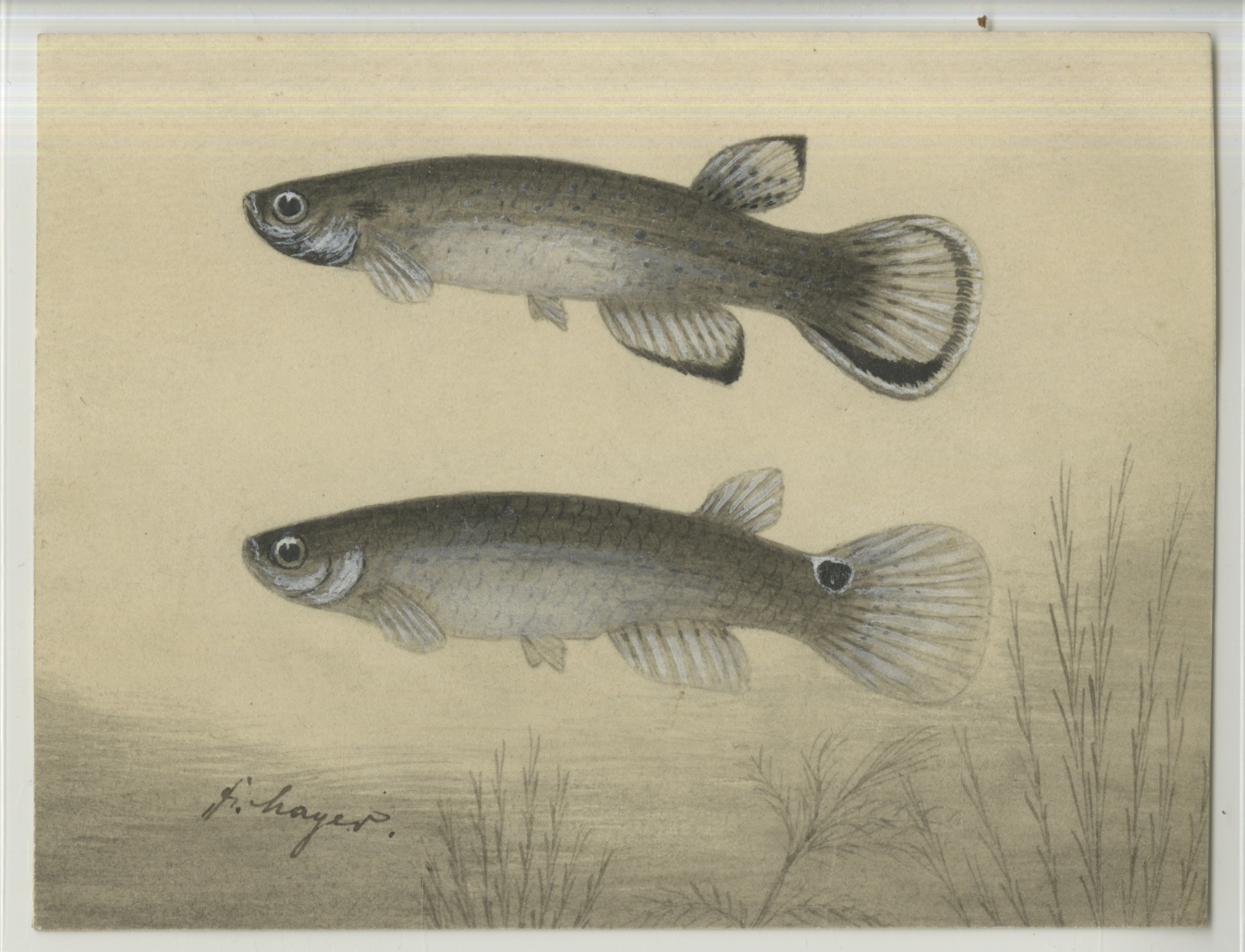

Isthmian rivulus

Fritz Mayer. Isthmian rivulus, [1933-1934]. William Innes Papers. Manuscript, original. (Mss. B In6)

Native to Central America, the isthmian rivulus is a freshwater fish that can be found in slow-moving bodies of freshwater, such as in brooks, creeks, and streams.

Molly

Fritz Mayer. Molly, [1933-1934]. William Innes Papers. Manuscript, original. (Mss.B.In6)

Mollies are a genus of fish native to the Americas. They were once primarily saltwater fish which have adapted to live in brackish water (fresh + saltwater) environments. They are typically found in tropical habitats where floods empty in to the ocean.

Montezuma swordtail

Fritz Mayer. Montezuma swordtail, 1933. William Innes Papers. Manuscript, original. (Mss.B.In6)

Originally found in Mexico, the Montezuma swordtail is recognizable by its distinctly-large tail. Males can have tails that equal the size of their bodies. The dominant male of a school sports the longest tail. "Monties" are a freshwater fish, typically swimming in rivers.

-

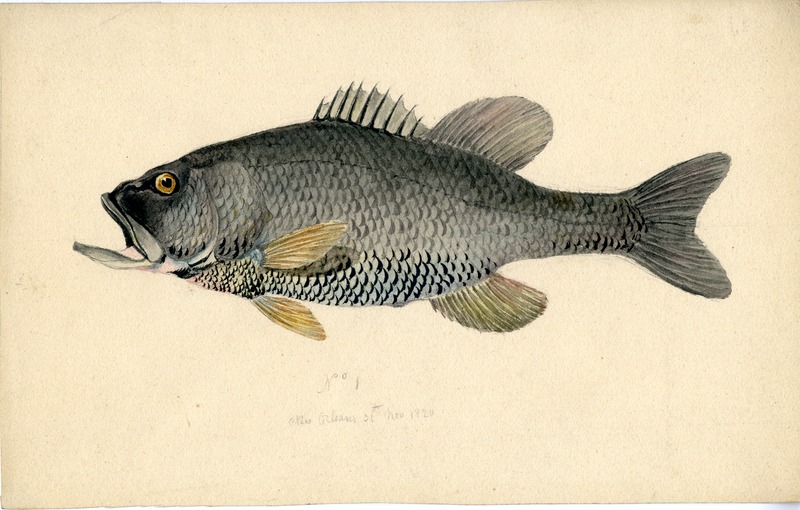

Fish

TR Peale (1799-1885). Fish, New Orleans, 1820. (Mss.B.P31.15d, no. 121)

Despite the moniker "New Orleans," this fish was likely encountered by Peale while a member of Stephen Harriman Long’s expedition to the Rocky Mountains. The Long Expedition of 1819-1820 began at St. Louis and ended at Fort Smith, Arkansas, taking in land west of the Missouri River. Peale embarked on several exploration missions during his life. He served as assistant naturalist during the Long Expedition.

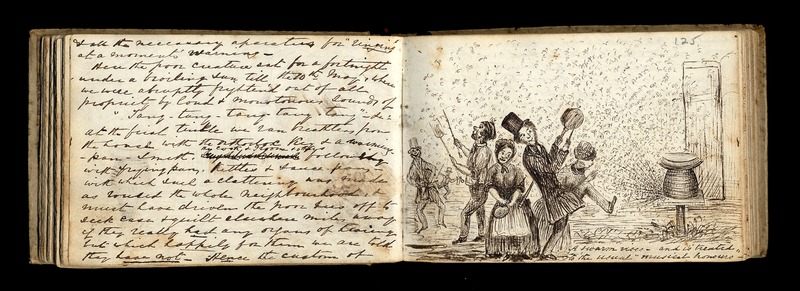

Bees

John Benbow (1800-1874). The Bee Book, “A swarm rises dash and is treated to the usual ‘musical honours’”, pages 124-125, 1846-1854. (Mss.630.4 B43)

John Benbow’s Bee Book is a small, copiously illustrated treatise and journal of beekeeping. The manuscript includes information on hive construction, seasonal management, the cleaning of hives, and other miscellaneous information culled both from printed sources and personal "experiments." The 44 pen and ink drawings include technical drawings of hives and beekeeping apparatus, along with humorous sketches of the activities of an "amateur apiarian."