Promoting Animal Knowledge

in the Modern Era Case Four

This page looks at man's relation with animals, in particular the notions of animal rights, welfare, and education. Political theorist Thomas Paine noted in The Age of Reason (1794): "The moral duty of man consists in imitating the moral goodness … of God towards all his creatures … [C]ruelty to animals is a violation of moral duty."

Thomas Young, a fellow at Trinity College in Cambridge, expanded upon this idea in his "An Essay on Humanity to Animals" (1804). Citing numerous passages from the Bible, Young demonstrated the importance to God of animals and the need for man to treat them with kindness and respect.

In 1838, Astronomer Thomas Forster penned a sentimental eulogy to his pet poodle, Shargs, his "best if not only friend." His eulogy is a touching tribute to an animal cherished as a member of the family, an animal full of intelligence, love, and devotion. Forster believed that all animals possess immortal souls, and that man should treat animals just as he would like to be treated.

The Pennsylvania Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals was formed in 1867, and in an Address from their founding year advocated for the need to improve the conditions for animals in American society.

Charles Darwin would have approved of such an endeavor: "Love for all living creatures [is] the most notable attribute of man," Descent of Man (1871).

In an essay entitled "Conscience in Animals" (1876), Canadian-born evolutionist George Romanes explored the possibility of animals possessing a conscience. He theorized that morality can only exist in beings which possess memory, the ability to reflect upon past conduct, intelligence, sociability, and the ability to show sympathy. He contended that, of animals, only monkeys, elephants, and dogs possess these traits.

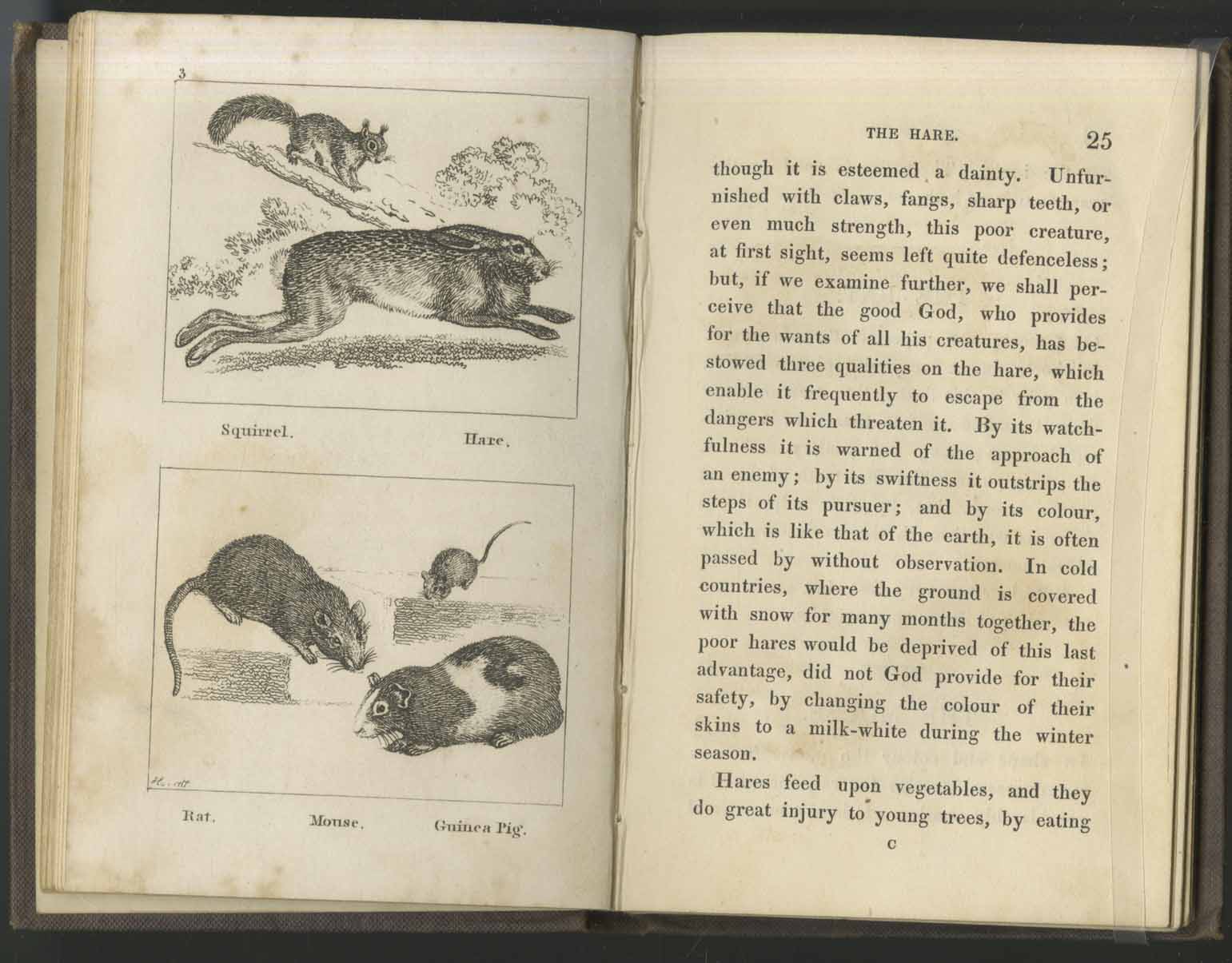

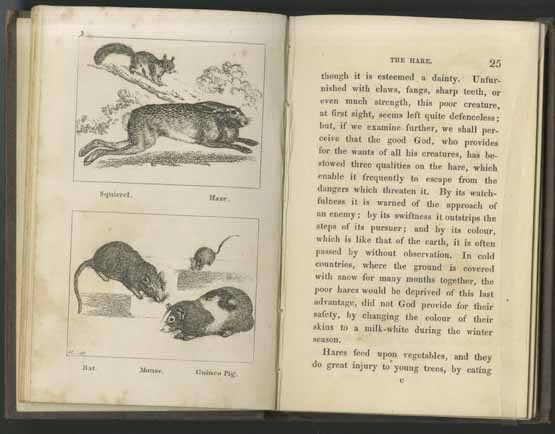

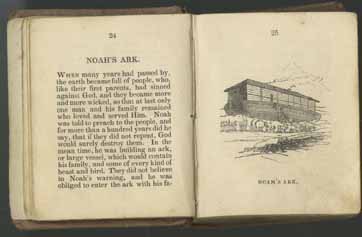

The notion of morality towards animals was something that was introduced to children during the early nineteenth century. Included here are several examples of children's literature relating to animals, from the personal library of Sarah Vaughan, niece of APS Librarian John Vaughan. The first is from an educational work and shows a passage about the hare. The writer informs the reader that "God provides for all the wants of his creatures" and has given the hare gifts to aid in its survival. The second text is a story about a little girl who kept pet birds. The author highlights the worth of the girl's diligence to her pets, and the importance of "duty to our fellow beings." The third and fourth texts are Biblical works for children. The story of Noah and his ark demonstrates to children that God remembers and values every living thing. Children in turn should treasure their fellow creatures. And, man and animal are in the same boat together.

The rest of the materials here come from twentieth-century collections at APS. A series of photographs demonstrates the breadth of manuscript collections in the library. Eugenicist Charles Davenport studied animals in the hopes of better understanding human heredity. Anthropologists Frank Speck and A. Irving Hallowell documented the importance of animals in Native American cultures. Paleontologist George Simpson is pictured posing next to a living animal (a baby guanaco) and the fossils of an animal (a tapir).

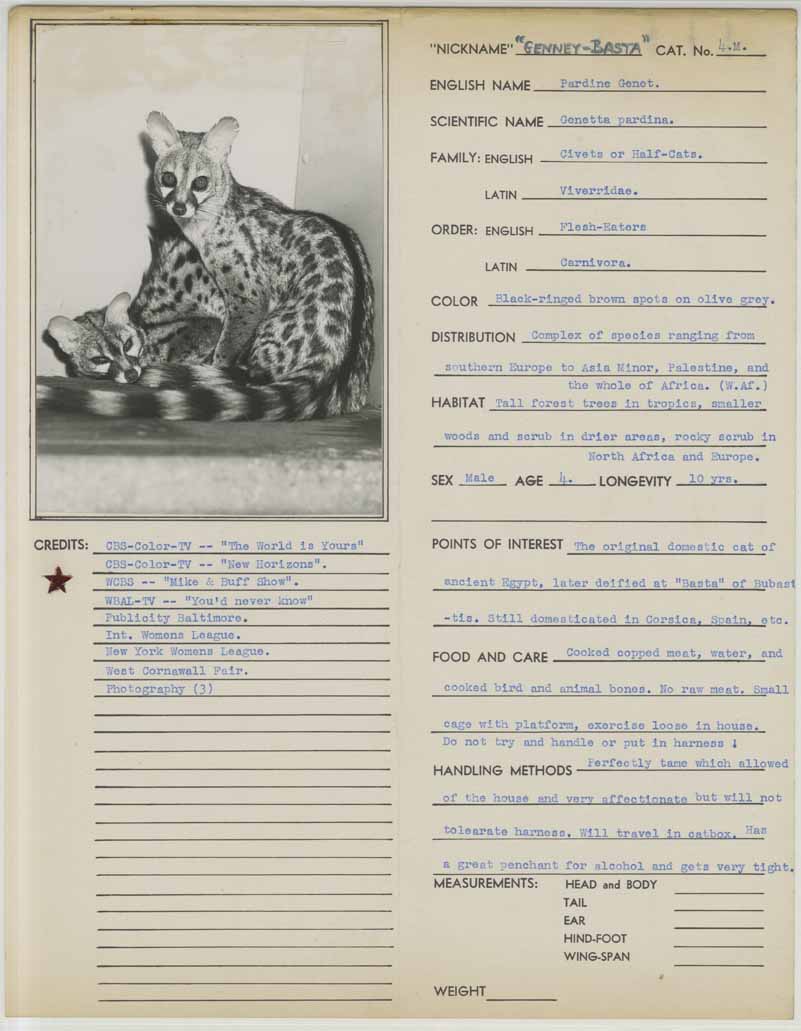

The final five documents come from the papers of Ivan Sanderson, a popular zoologist in post-World War II America. A Scot educated in botany and zoology at Cambridge University and a spy for the British forces during the war, Sanderson was best known in the U.S. for his regular appearances along with his animals on radio and television in the 1950s and 1960s. Sanderson founded a company called "Animodels," to care for and publicize his animal partners. Note the entry from his Animodel book for Genney-Basta, a civet. Sanderson was also an accomplished writer and artist. Here is a sketch of elephants for a children's book; and two stunning drawings of a lion and an Egyptian domestic cat.

Image Gallery

-

Paine

Thomas Paine (1737-1809), The Age of Reason, page 55, 1794. (Paine 8, 1794-1795 Le3)

An ardent republican and critic of monarchy, Paine left his native England in 1792 for revolutionary France, where he took a seat in the National Convention. In the vote that decided the fate of King Louis XVI, he opted for exile, rather than execution. This stance offended the ruling Jacobins, and Paine was imprisoned from December 1793 to November 1794. During this time, Part I of The Age of Reason was published. Part II was published in 1795, and part of Part III in 1807. In this work, Paine severely criticized organized religion, and his words were widely misinterpreted as a defense of atheism.

-

Young

Thomas Young (1772-1835), An Essay on Humanity to Animals, 1804. (PAM v.131, no.6)

An Anglican priest and Senior Tutor at Trinity College, Cambridge, Young was a pioneering advocate for animal welfare. The pamphlet on exhibit here is an abridged version of Young’s book of the same name, An Essay on Humanity to Animals (1798). Versions of his essay were printed several times in an attempt to garner public support for the plight of animals. Young contended that violence towards animals leads to violence towards humans; the character of a person can be weighed based upon how they treat animals; and it is in humanity’s best interest to treat animals well. Citing Biblical passages, he demonstrates that God cares for animals and calls on humanity to do likewise. Because animals are sentient and can feel both pleasure and pain, just as mankind can, "we must conclude that the Creator wills the happiness of these his creatures." To read Young’s pamphlet, please see the "Full Text" page of this exhibit.

-

Forster

T. Forster (1789-1860), Eulogy of Shargs, A Favourite Dog, 1838. (PAM v.6, no.10)

Thomas Ignatius Maria Forster was a graduate of Corpus Christi at Cambridge University, where he studied astronomy. In addition to astronomy, he published works on natural history, education, phrenology, and poetry. For his beloved canine friend Shargs, he penned the following poem, "On the Tomb of Shargs" (Philosophia Musarum, 1838):

As o’er the pansied grave we jog, Of ilka lov’d and honourd dog,What tears o’ sorrow flow. For though in each succeeding race The faint resemblance we may trace, Of those who rest below. The selfsame dear confiding friend, As him for whom our hearts we rend Will near again be given. The dearest that I ever knew Today demands the pious vow, That we may meet in Heaven.

Clearly, Forster believed in an afterlife for animals and that "animals and men have a common destiny" (Philozoia, 1839). To read Forster’s eulogy of his pet, please see the "Full Text" page of this exhibit.

-

SPCA

Pennsylvania Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, Address, 1867. (PAM v.1014, no.17)

The first organization to concern itself specifically with the rights of animals in the Western Hemisphere, the American Society for the Prevention of the Cruelty to Animals was founded in 1866 "to provide effective means for the prevention of cruelty to animals throughout the United States." The Pennsylvania chapter of the society was founded a year later, in 1867. The pamphlet above largely focuses on improving conditions for the horses and dogs of Philadelphia. To read it, please see the "Full Text" page of this exhibit.

-

Darwin

Charles Darwin (1809-1882). Descent of Man, 1871. Printed work, 1st edition. (VAL 575 D25d.1b)

Darwin published Descent after his pioneering work on evolution in animals, On the Origin of Species (1859). He wrote Descent in order to explore whether man "descended from a pre-existing form; ...the manner of his development; and...the value of the differences between the so-called races of man."

-

Romanes

George John Romanes (1848-1894). Conscience in Animals, 1876. (590 Pam No.32)

A contemporary and personal friend of Charles Darwin, Romanes was raised in London and educated at Cambridge University. His works touch on the fields of evolution, physiology, and animal psychology. His efforts in animal psychology were criticized by other scholars as being unproven and anthropomorphic. Regardless of whether his arguments were influential or not, Romanes’ writings did effectively generate debate. To read his essay "Conscience in Animals," please see the "Full Text" page of this exhibit.

-

Hare

Footsteps to the Natural History of Beasts and Birds, Hare, 1836. Printed work, 5th ed. (VGN 808.068 F735.5)

This work aims to educate children about their fellow creatures. Writing from a Christian perspective, the author provides facts about a variety of animals, noting traits and capabilities given to each by their Creator.

-

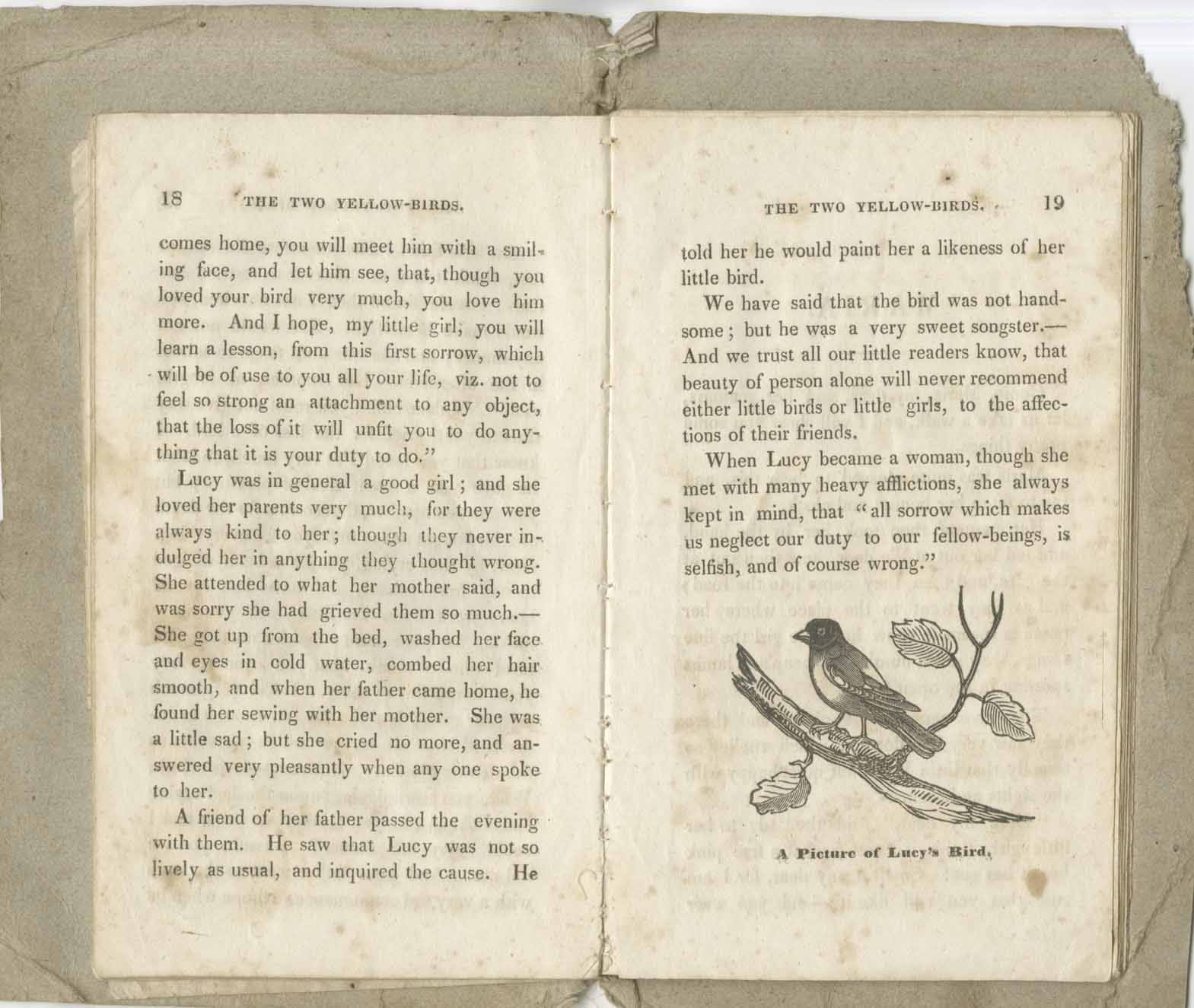

Yellow-birds

The Two Yellow-Birds, 1838. Printed work. (VGN 808.068 T93)

Aimed at children readers, this charming story about a girl and her pet birds underlies the importance of responsibility, sacrifice, and duty. Though only six years old, Lucy never once forgot to give her bird fresh seeds and water, or to clean his cage. While Lucy experienced tragedy when her little bird died, she learned that "all sorrow which makes us neglect our duty to our fellow-beings is selfish and...wrong." To read the full story, please see the "Full Text" page of this exhibit.

-

Noah

History of the Bible, Noah, 1839. Printed work. (VGN 808.068 H62b)

“The infant must be taught to cherish and protect every living creature" (Thomas Forster, Philozoia, 1839). This miniature children’s book by an unknown author measures 2 inches x 1.75 inches. A little book for a little audience.

-

Noah's Ark

Isabella Child, The Little Picture Bible, Noah's Ark, [1830-1840]. Printed work. (VGN 808.068 C433l)

This little book is part of a 12-book series for children entitled "My Own Library" published by Charles Tilt of London around 1835. Each of the little books measures 3 inches x 1.5 inches.

-

Davenport Cat

Charles Davenport (1866-1944). Charles Davenport with Cat, 1909. Charles Davenport Papers. Photograph. (Mss.B.D27, U5-1-110)

Possessing a doctorate in zoology from Harvard, Davenport is best known for directing the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and for championing eugenics. Under his leadership, Cold Spring Harbor became a laboratory devoted to the integration of physics, chemistry, and physiology into experimental evolutionary biology and genetics. Davenport was drawn particularly to applying genetic theory to the "betterment" of human populations. He sought particularly to unveil the scientific basis for the inheritance of physical, mental, and moral characteristics in human populations with the goal of eventually breeding better humans.

-

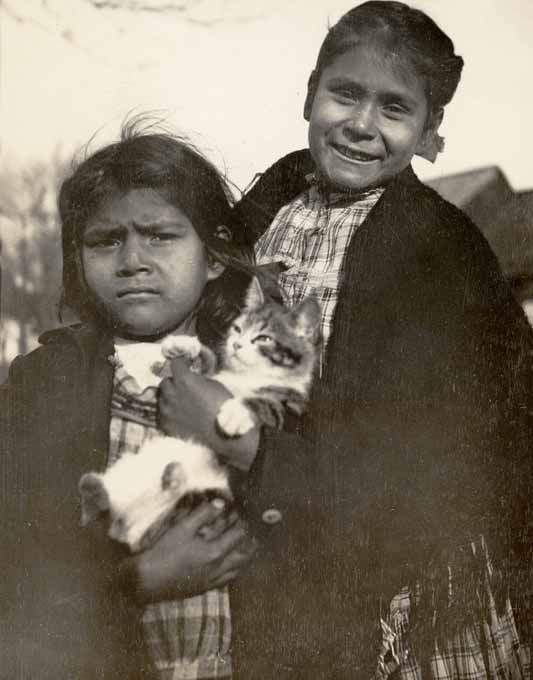

Penobscot Cat

Frank Speck (1881-1950). Penobscot Girls, Holding Cat, undated. Frank Speck Papers. Photograph. (Mss.Ms.Coll.126, Image 9-2-d)

A common theme in Native American belief systems is the notion of animism, which views all aspects of nature as possessing a spirit. Animals are kindred spirits. "Every seed is awakened and so is all animal life. It is through this mysterious power that we too have our being and we therefore yield to our animal neighbors the same right as ourselves, to inhabit this land." – Sitting Bull

-

Penobscot Dog

Frank Speck (1881-1950). Group Portrait of Man, Woman and Child, Standing Outside, Man Holding Dog, 1914. Frank Speck Papers. Photograph. (Mss.Ms.Coll.126, Image 9-16-j)

Speck was an anthropologist and ethnographer who taught at the University of Pennsylvania. He studied the Eastern Woodland Indians. In the field, Speck was a "bedside ethnologist," staying with the people all day, eating with them, learning their language, and sleeping in the village. This sense of ease and intimate form of fieldwork allowed Speck to gain the trust of the tribes, facilitating his collection of data. One aspect which Speck chose to focus on was a tribe’s link to nature, with ethnobiology, material culture, and uses of the environment playing major themes in his work.

-

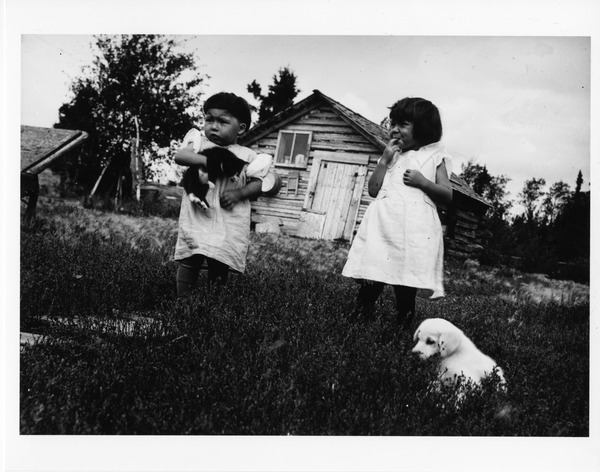

Ojibwa Kitten and Puppy

A. Irving Hallowell (1892-1974). Ojibwa Boy and Girl with Puppy and Kitten, 1930-1933. A. Irving Hallowell Papers. Photograph. (Mss.Ms.Coll.26, Series VI, Image A25)

A cultural anthropologist who studied under and taught with Frank Speck at the University of Pennsylvania, Alfred Irving ("Pete") Hallowell was best known for his studies of Ojibwa culture and world-view. Hallowell’s field studies, which began in the late 1920s, involved the Abenaki of Quebec; the Montagnais-Naskapi of Labrador; and especially the Ojibwa-speaking peoples of the Lake Winnipeg region. His studies provide a complete ethnographic record of Ojibwa culture, including aspects of kinship and social organization, economics, technology, ecological relationships, medicine, religion, and folklore. Hallowell went beyond ethnological issues to those involving the psychological dimensions of Ojibwa acculturation. His use of clinical psychological methods, especially Rorschach tests, was both innovative and controversial in his discipline.

-

Simpson Guanaco

George Simpson (1902-1984). George Simpson with Baby Guanaco, 1930. George Simpson Papers. Photograph. (Mss.Ms.Coll.31)

A specialist in Mesozoic and early Cenozoic mammals, Simpson’s contributions to the fusion of Darwinian natural selection and Mendelian genetics were both empirical and theoretical. Simpson was one of the most influential paleontologists of the twentieth century, helped in part by his ability to write successfully for both a technical, professional audience and a popular audience. Here he is pictured with a young guanaco. The guanaco is a member of the camel family related to the llama, alpaca, and vicuna, and is native to the mountainous areas of southeastern South America. Simpson encountered this guanaco while visiting the Torres del Paine National Park in Patagonia.

-

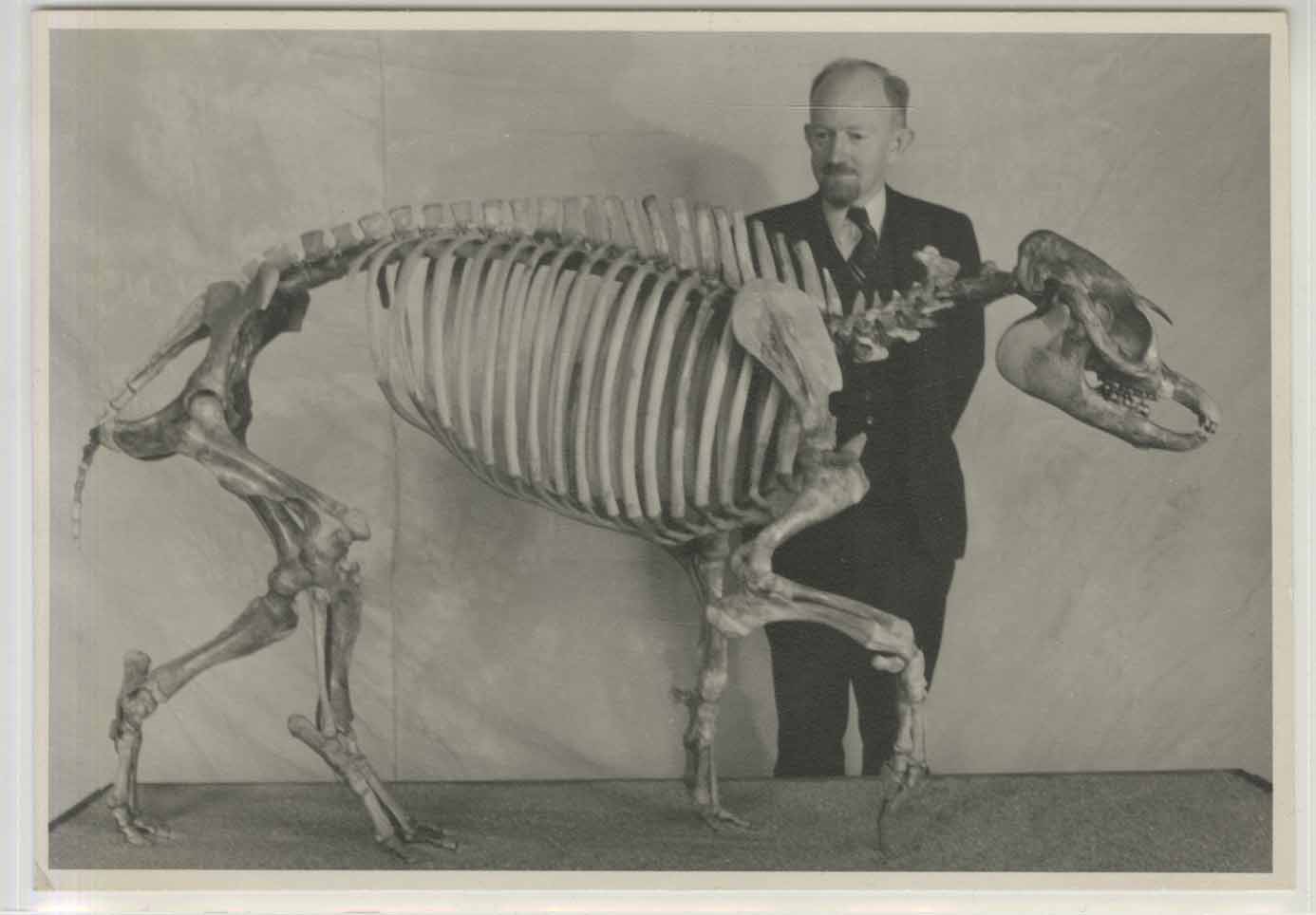

Simpson Fossil

George Simpson (1902-1984). George Simpson with Fossil Tapir Skeleton, 1944. George Simpson Papers. Photograph. (Mss.Ms.Coll.31)

One of the seminal figures in the emergence of the Modern or Neo-Darwinian Synthesis during the mid-twentieth century, Simpson helped define the unique contribution made by vertebrate paleontology to the life sciences. Here he is pictured with the fossilized skeleton of a tapir, a hooved animal in the same order as the horse and rhinoceros. Known for its prehensile snout, the tapir is native to South and Central America, and Southeast Asia.

-

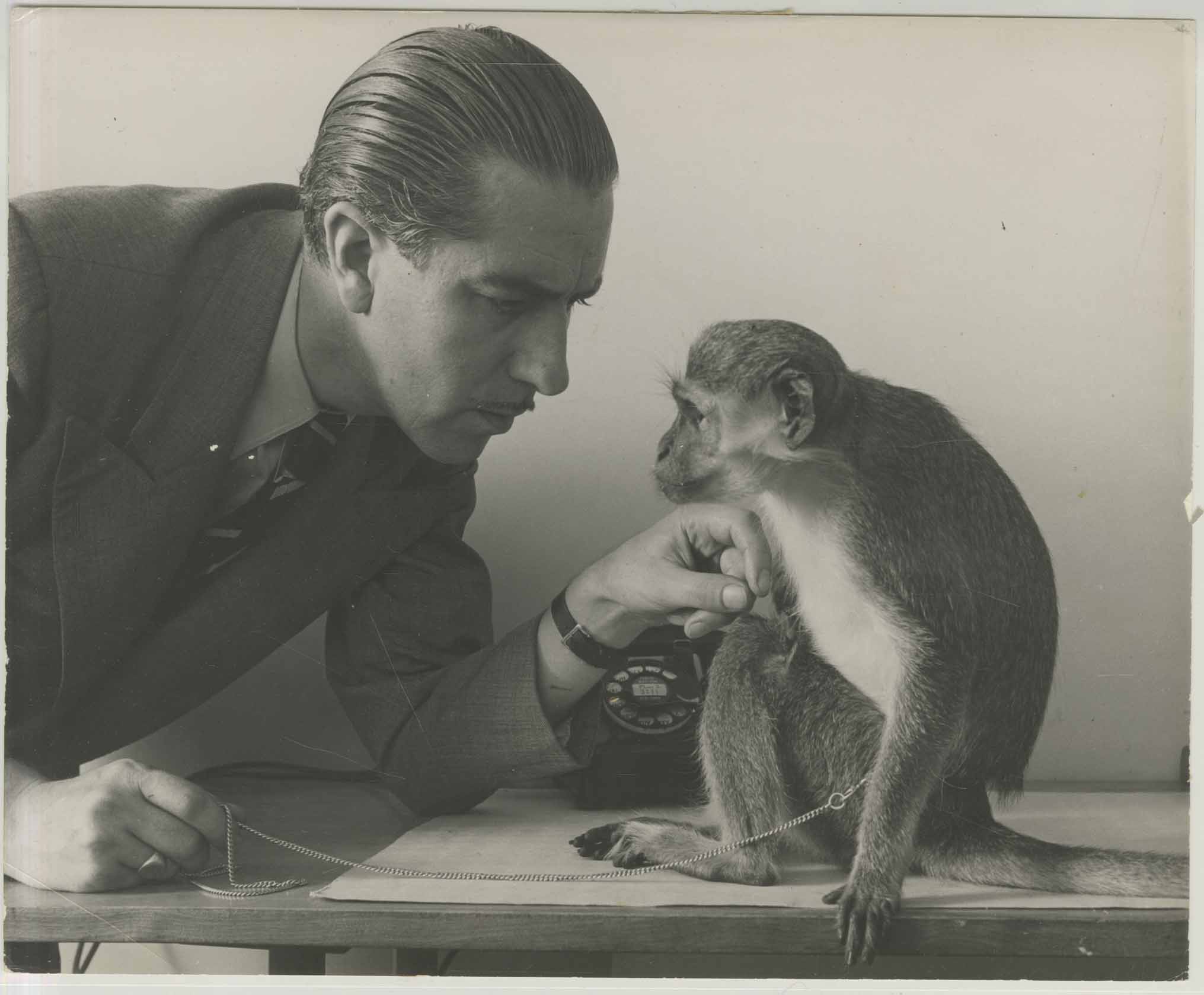

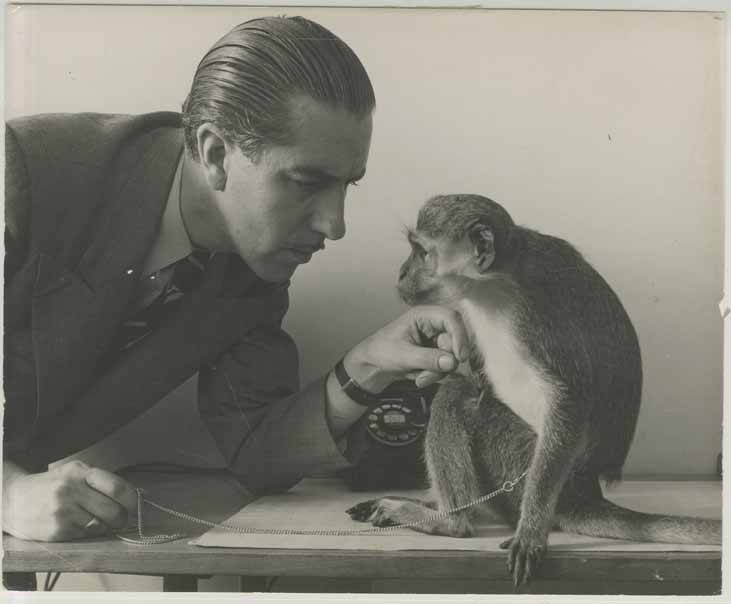

Sanderson Monkey

Ivan Sanderson (1911-1973). Ivan Sanderson with Monkey, undated. Ivan Sanderson Papers. Photograph. (Mss.B.Sa3)

"Today we not only accept the oneness of Nature as the creation of a superior power, but also in lieu of demanding a separate creation for ourselves, we have come to accept, and to accept with considerable humility, a small allotted place in something much greater." –Ivan Sanderson, The Monkey Kingdom (1957)

-

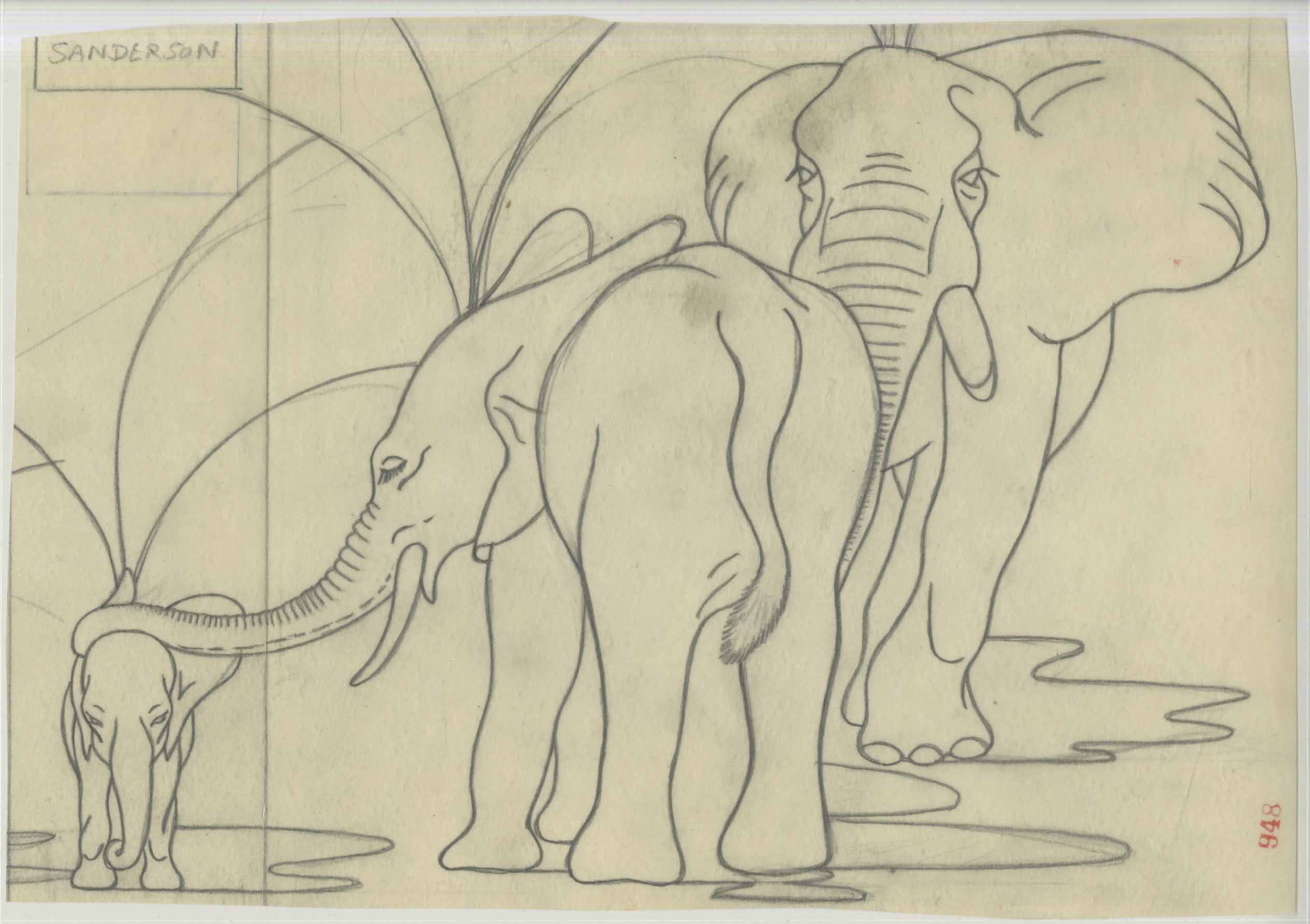

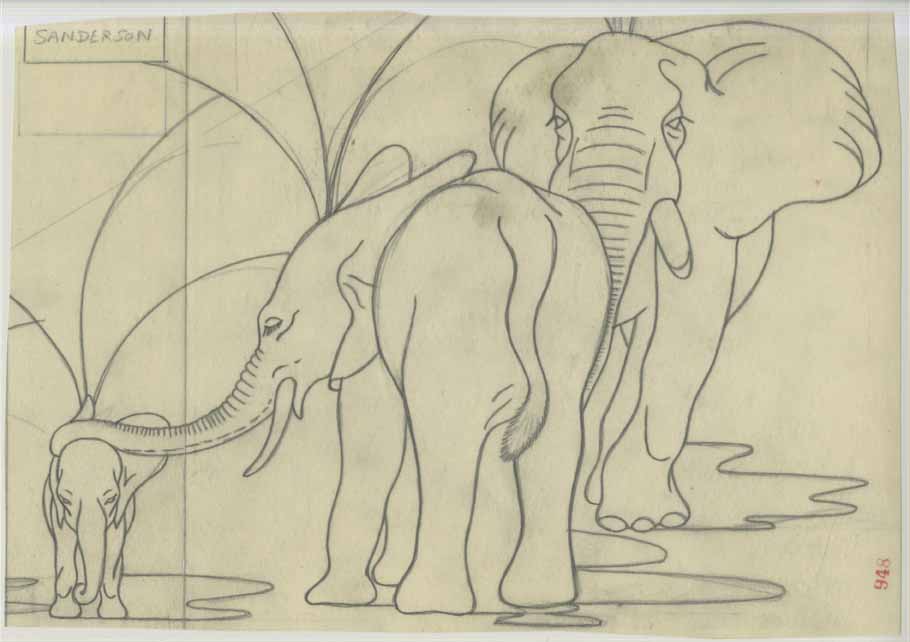

Elephants

Ivan Sanderson (1911-1973). Elephants, 1962. Ivan Sanderson Papers. Manuscript, original. (Mss.B.Sa3)

Sanderson drew this image for the book The Dynasty of Abu: A History and Natural History of the Elephants and Their Relatives, Past and Present (1962). The book is an exploration of Abu--loxodonts, olifonts, and their extinct relatives. The common word for these animals is "elephant," but Sanderson notes that that term refers to only one specific type of Abu.

-

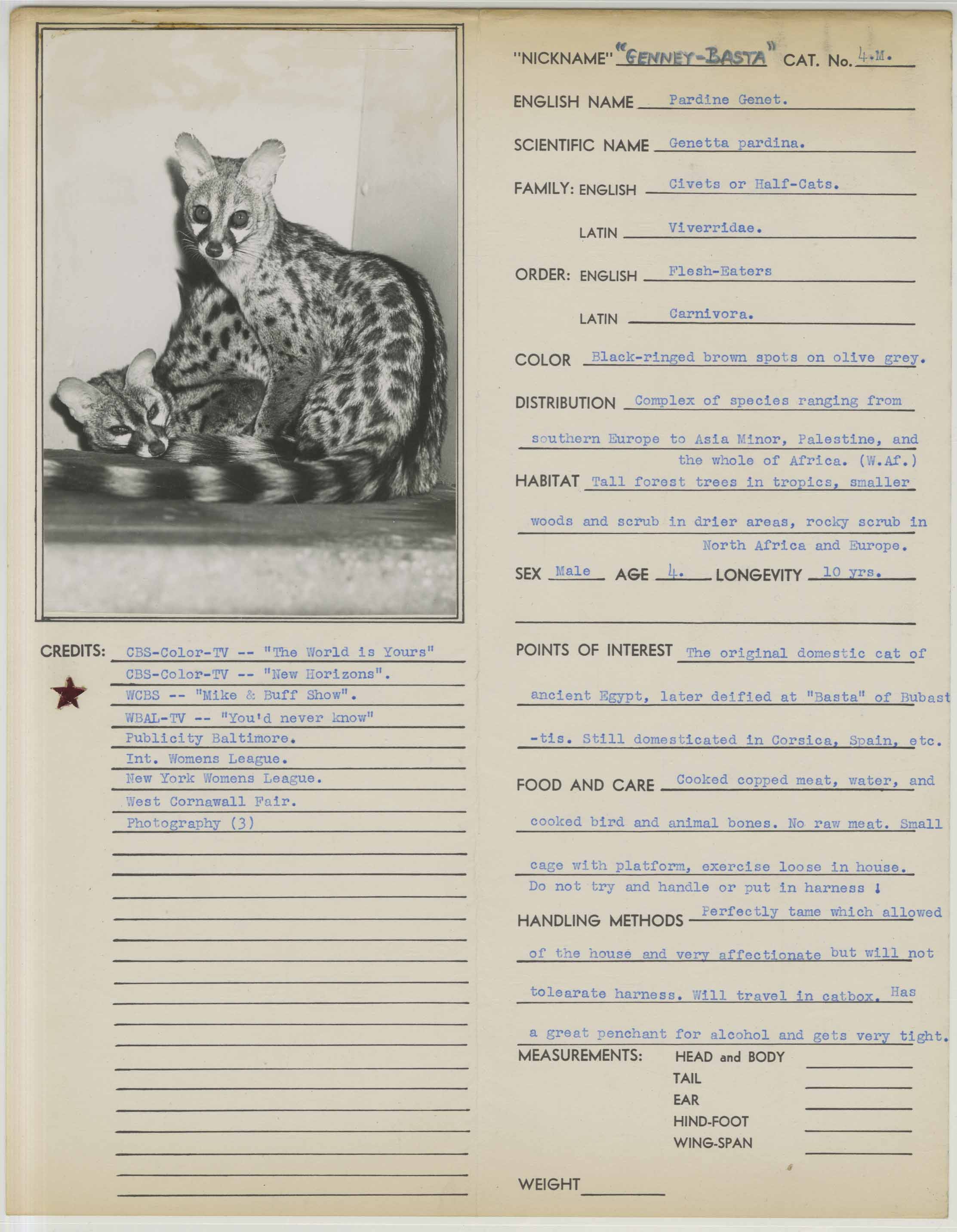

Civet

Ivan Sanderson (1911-1973). Animodels Scrapbook. “Genney-Basta”. Pardine Genet, [1952-1958]. Ivan Sanderson Papers. Manuscript, original. (Mss.B.Sa3)

This page comes from the Animodels Scrapbook, a portfolio of animals used by Ivan Sanderson during his public appearances. Above all, he sought to educate the public of all ages about animals. In an essay written for My Baby and Young Years magazine, he wrote: "You can help your child to develop a wholesome attitude towards animals by teaching him never to tease them or violate their natural dignity...Above all, instill in your child a mutual respect between men and other animals" (Don’t Pull His Tail, 1950).

-

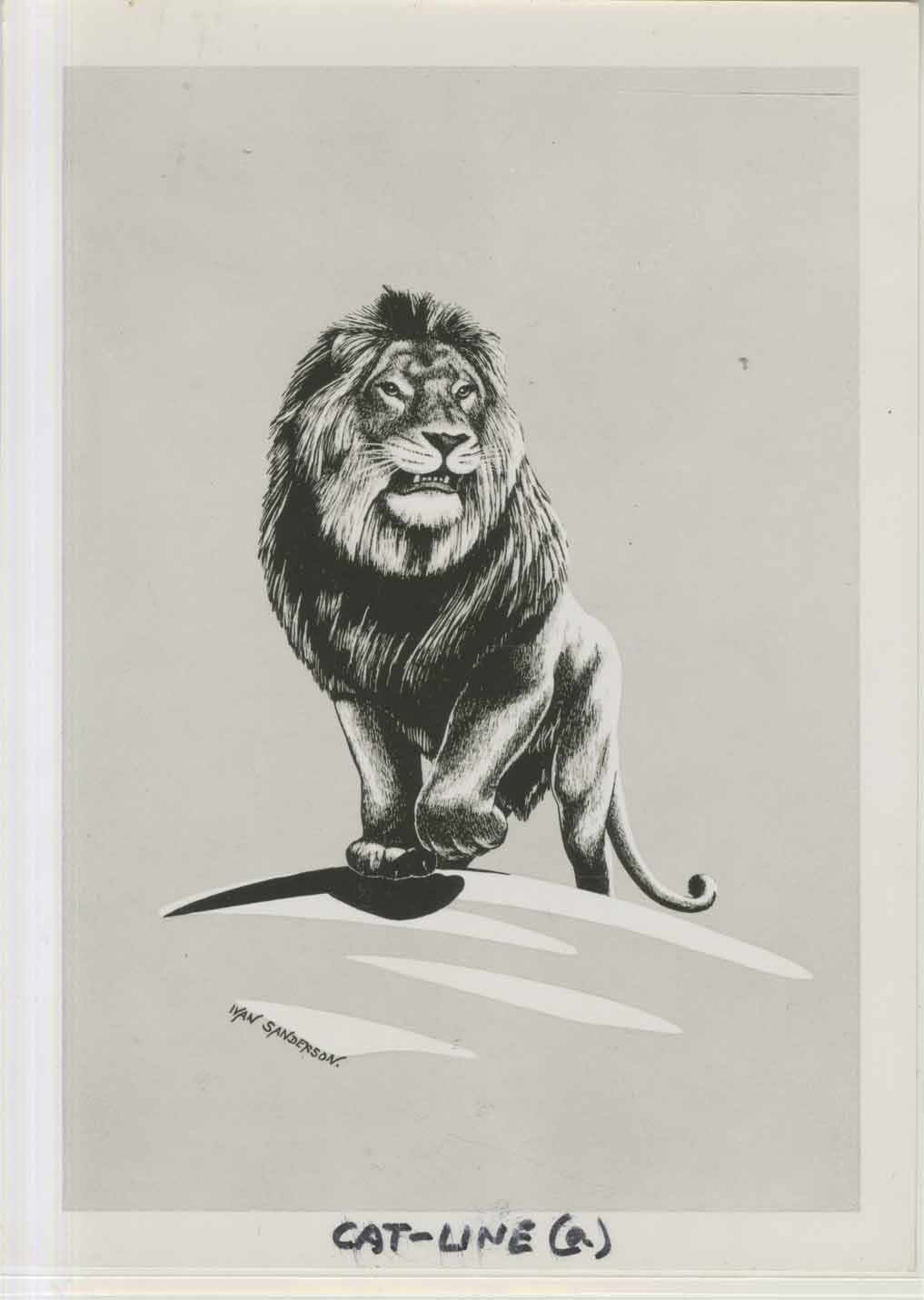

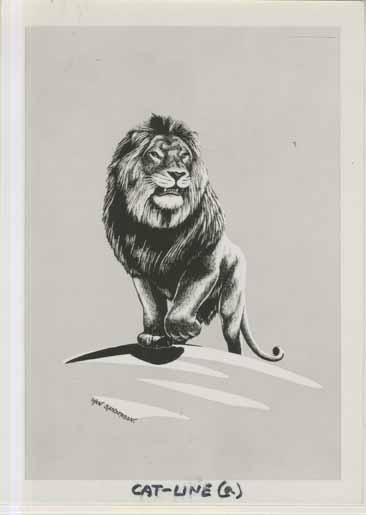

Lion

Ivan Sanderson (1911-1973). Cat - Line (a). Lion, 1946. Ivan Sanderson Papers. Manuscript, original. (Mss.B.Sa3)

Sanderson drew this image for the book Animal Tales: An Anthology of Animal Literature of All Countries (1946). About the lion he wrote:

The lion has always been regarded as the King of the Beasts, and he is the symbol of Africa. He has a noble mien and has been credited with a noble personality...The lion is a mild-tempered creature unless molested. By day, he will lie in the open and allow men to walk close by him or to drive a car within inches of his softly tapping tail. If a man meets a lion unexpectedly face to face on a path, no altercation will take place...His maned majesty will watch intently... [,] develop an unexpected concern for some quite irrelevant thing... [and] will quietly turn and wander off...At night, however, he is not an animal to be trifled with.

-

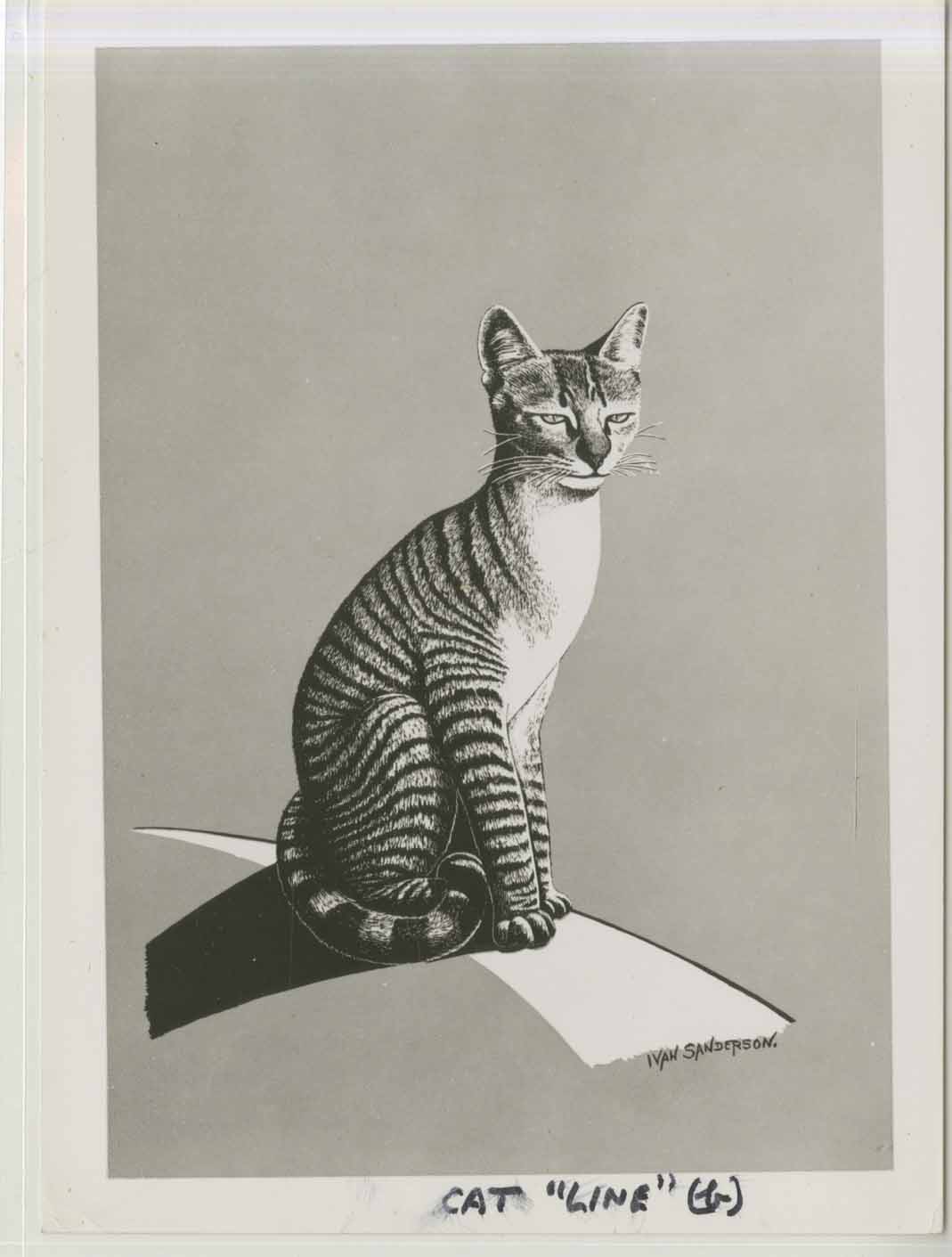

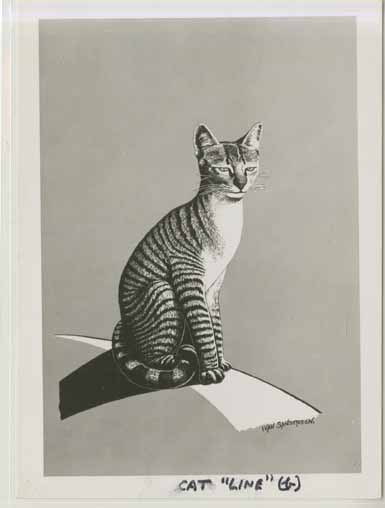

Egyptian Cat

Ivan Sanderson (1911-1973). Cat - Line (b). Egyptian Domestic Cat, 1946. Ivan Sanderson Papers. Manuscript, original. (Mss.B.Sa3)

Sanderson drew this image for the book Animal Tales: An Anthology of Animal Literature of All Countries (1946), which he compiled and edited. The work is organized by locale, with Sanderson leading the reader on a journey:

We...have reached the rose-tinted mirror waters of Egypt where bowing palms and sand-scarred, megalithic columns are reflected between the sandbars...We now stand alone by the waters of the Nile...A cat...descends the bank with a majestic air and takes up a position by the waters’ brink. It sits down; it curls its tail about the pedestal of its feet; it closes its eyes; it ceases to move. In the silence of the sand it is planted like a sphinx. It appears very holy. And, by Jove, it is holy!