The Search for Animal Knowledge

in the Age of Jefferson Case One

As a member of the American Philosophical Society (APS) for forty-six years (1780-1826) and as president of the society for seventeen years (1797-1814), Thomas Jefferson left his mark on the pursuit for useful knowledge. He played a vital role in the collecting activity of the society. By inspiring scientific expeditions and securing their findings for the society, he contributed greatly during a fruitful period in the pursuit of natural history. This page contains materials relating to the pursuit of animal knowledge in the time of Jefferson, during the early American republic.

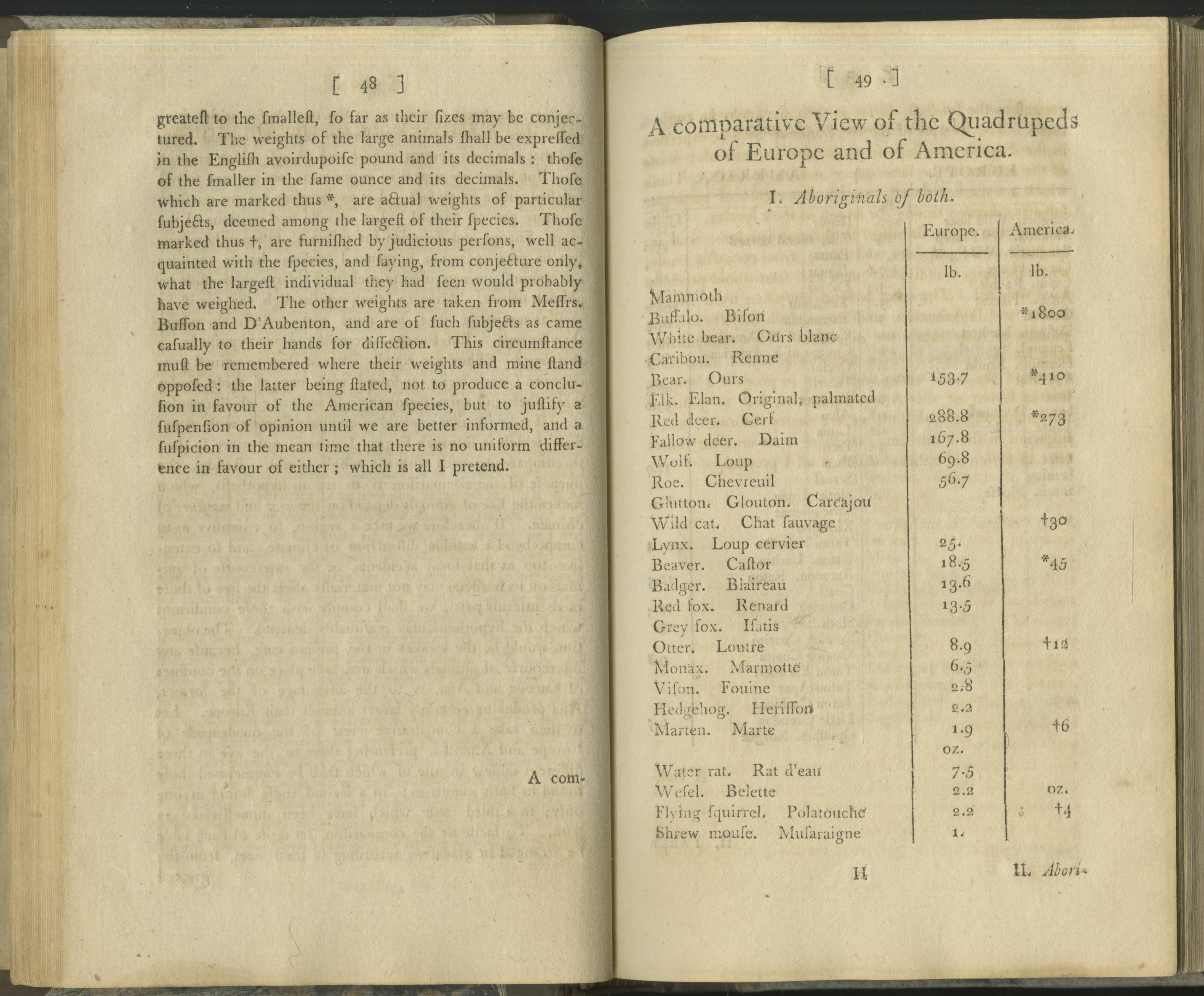

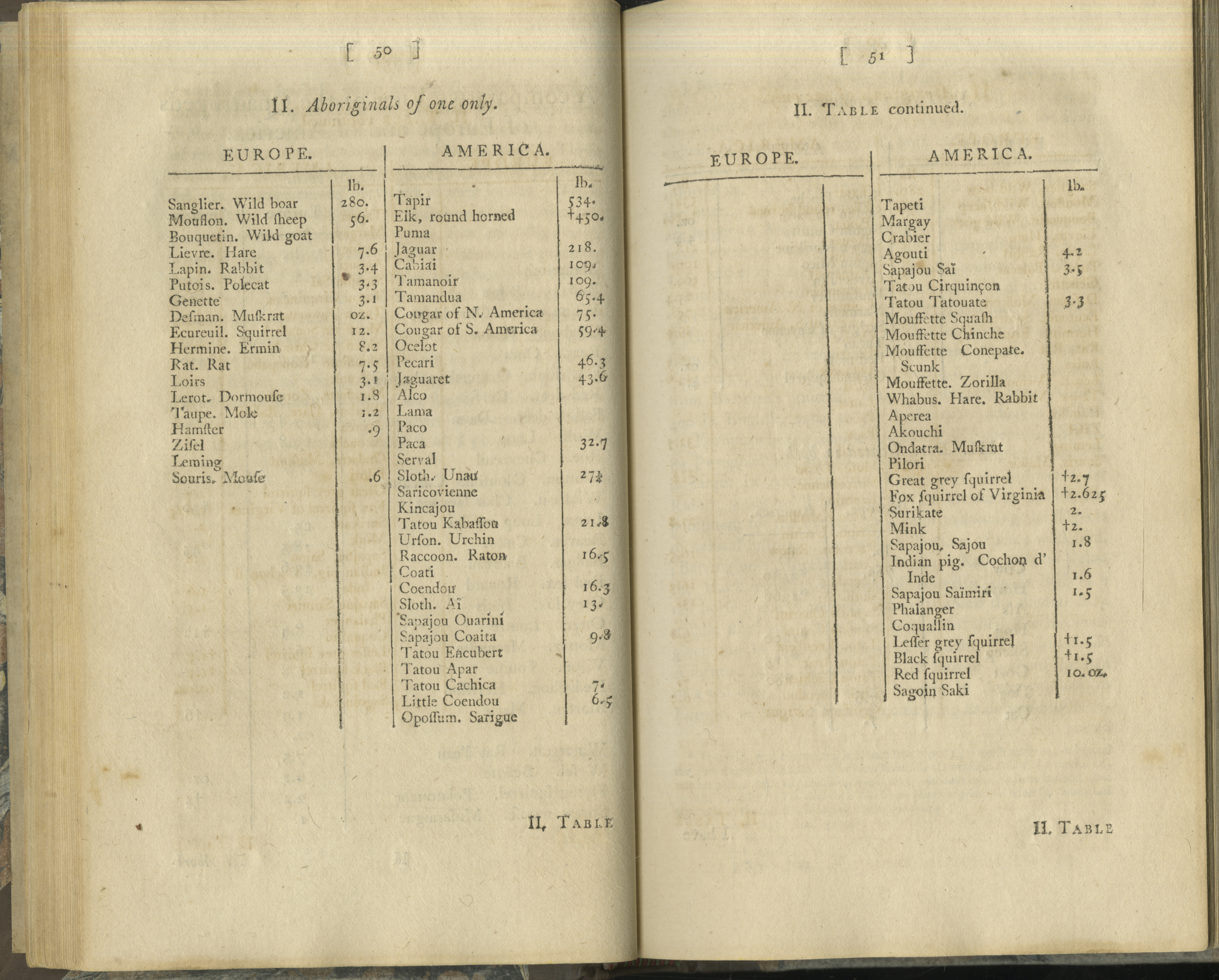

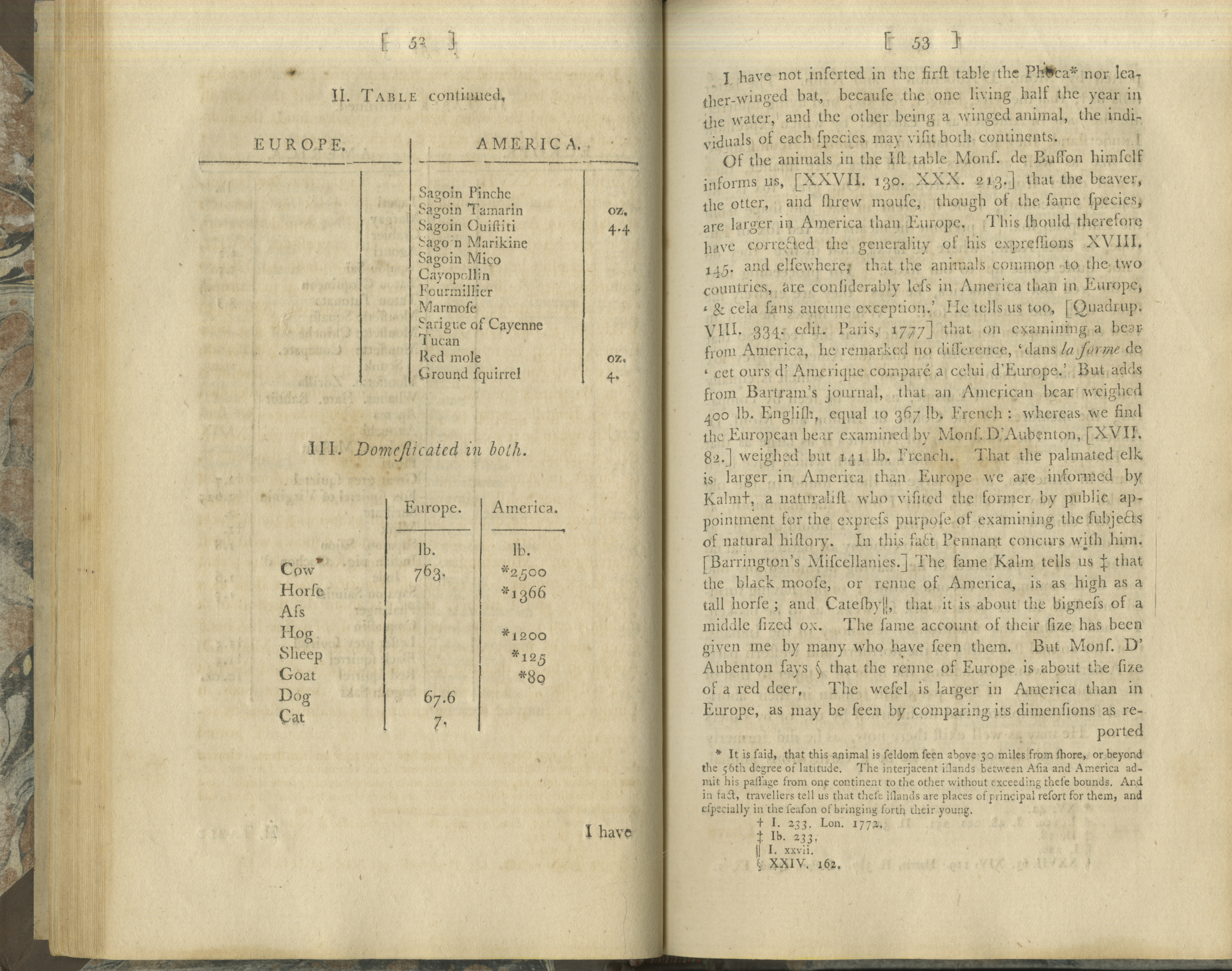

In Notes on the State of Virginia (1785), Jefferson sought to show the vitality and strength of American animals when compared to their European counterparts. In a series of charts, he compared and contrasted the weights of animals in the two continents. The work was a direct challenge to the claim of French naturalist Georges Buffon, who purported that American animals were inferior to those found in the Old World. Jefferson proved otherwise.

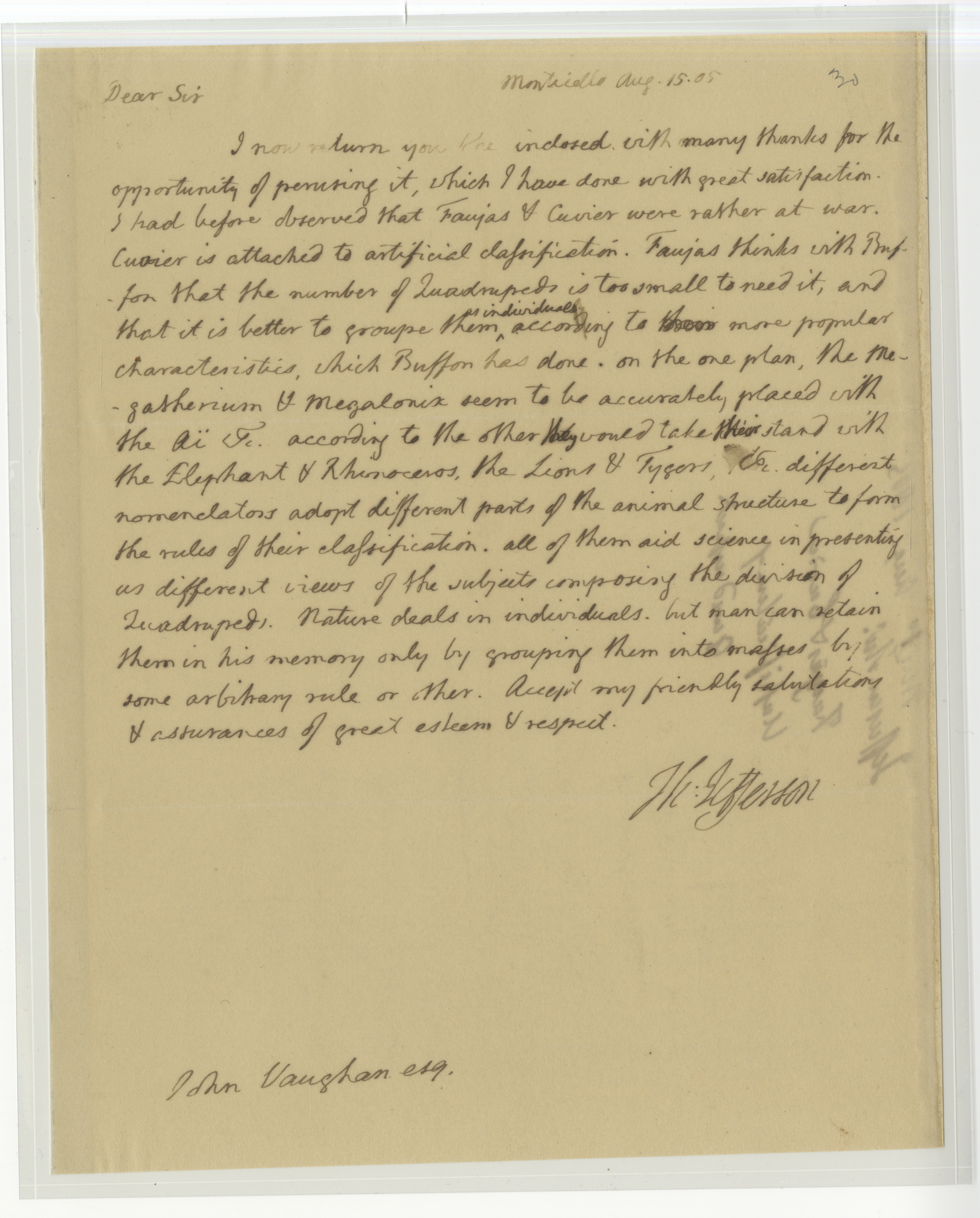

In a letter to APS Librarian John Vaughan from 1805, Jefferson notes the importance of classifying animals: "Nature deals in individuals, but man can retain them in his memory only by grouping them into masses by some arbitrary rule or other." In particular, Jefferson was interested in the categorization of the Megalonyx, a prehistoric creature which he believed still roamed the American countryside.

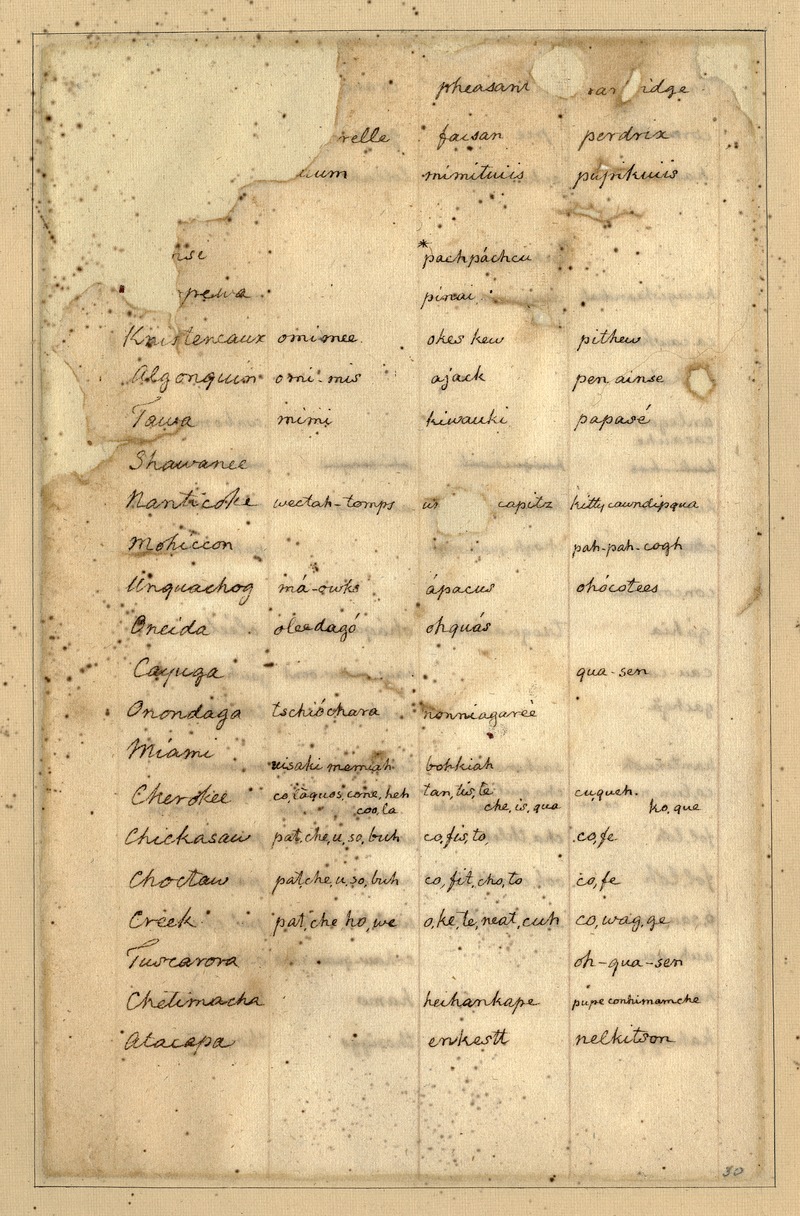

Jefferson also sought to classify the languages of Native Americans in an attempt to determine their history. Included here is a page from his effort, showing the translation of "pheasant" and "partridge" into numerous tribal languages.

Perhaps Jefferson's greatest gift to the APS, and to American science, was his championing of scientific exploration. As president both of the country and APS, Jefferson played a vital role in arranging federal sponsorship of the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804-1806. After the Louisiana Purchase, the young republic had vast swathes of unchartered land, land that was inhabited by scores of uncataloged animals. The exploratory mission was charged with documenting and collecting hundreds of plant, animal, and fossil specimens from the trans-Mississippi west. The written products of the expedition, , were given to the APS by Jefferson.

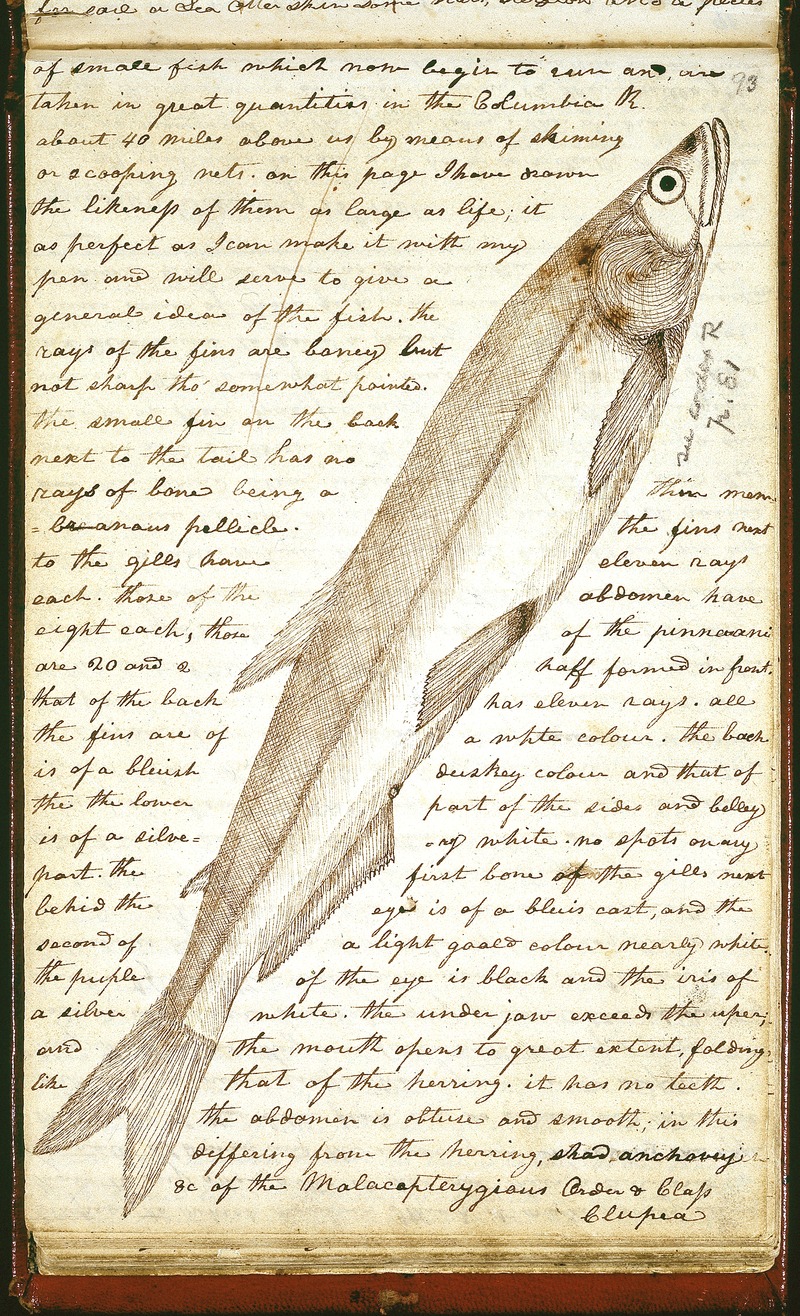

While in the field, Captain Meriwether Lewis encountered dozens of animals, some of which he sketched in his journals, including the stunning White Salmon Trout. Working from specimens brought back from the expedition, naturalist/artist Charles Willson Peale drew "The Fisher" and "Two Birds." The birds are a Mountain Quail and a Lewis Woodpecker, two species discovered by Lewis on the expedition.

Peale was an avid naturalist who sought to promote natural history to the public at large. From 1795-1810, he directed a natural history museum in APS' Philosophical Hall (the current site of the APS Museum). The Peale Museum housed numerous specimens brought back from scientific explorations. Peale's son Titian Ramsay Peale, himself an enthusiastic naturalist-explorer, painted the "Missouri Bear" from two animals which Jefferson presented to the Peale Museum from Zebulon Pike's explorations.

The further illustrations on this page by Benjamin Smith Barton, William Bartram, and Titian Ramsay Peale come from additional scientific exploratory missions to Jefferson's America.

Image Gallery

-

Notes on the State of Virginia

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826). Notes on the State of Virginia. 1788. Printed work, 1st U.S. edition. (917.55 J352)

Jefferson wrote Notes in part to refute the work of French naturalist Georges Buffon who hypothesized that America’s landscape, animals, and native inhabitants were inferior to their European counterparts. Throughout his work, Jefferson uses examples of indigenous plants and animals and Native American cultures as proof that America was equal if not superior to Europe in beauty, grandeur, and sophistication.

-

Dog

Benjamin Smith Barton (1766-1815). Dog of the American Indians, n.d. Benjamin Smith Barton Papers. (Mss. B B284d)

Barton was a physician, naturalist, and professor at the University of Pennsylvania. He was one of the central figures in Philadelphia’s early national scientific establishment. A prolific author, he established his reputation as one of the nation’s preeminent botanists through his botanical text book The Elements of Botany (1803), but his contributions to zoology, ethnology, and medicine were equally noteworthy. Barton had a deep interest in Native American culture and linguistics and studied them throughout his life. He became one of the foremost experts on the subject and advised Lewis and Clark before they departed on expedition.

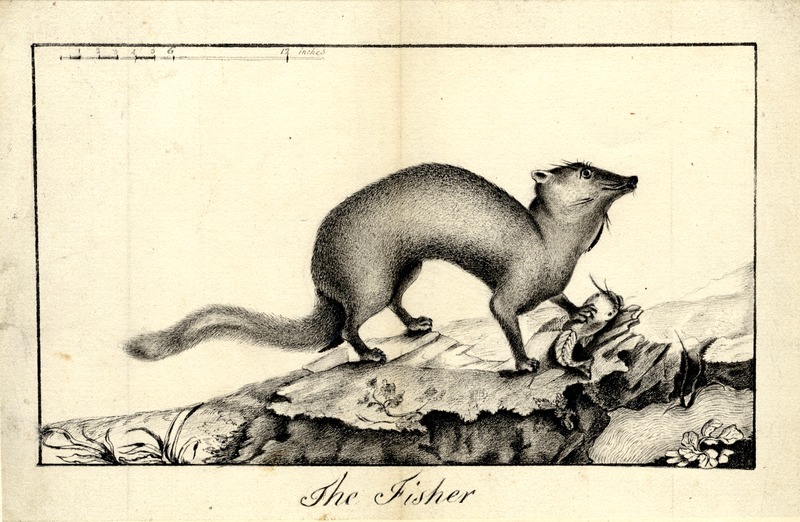

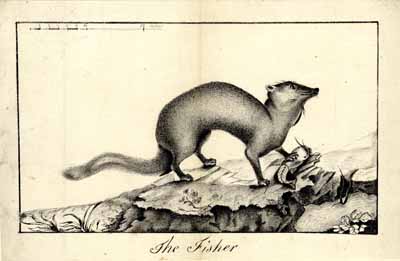

Fisher

Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). The Fisher, n.d. Lewis and Clark Journals, Volume VII. (Mss. 917.3 L58)

Peale was a prodigious artist. During his life, he produced more than one thousand paintings, including hundreds of portraits of leading Americans during the colonial and early national periods. This image was drawn from a specimen brought back from the Lewis and Clark expedition. Of the fisher, William Clark noted:

How this animal obtained the name of fisher I know not, but certain it is, that the name is not appropriate; as it does not prey on fish, or seek it as a prey. They are extremely active strong and made for climbing which they do with great agility, and bound from tree to tree in pursuit of the squirrel or Raccoon, their natural and most usual food (19 February 1806).

While it is true that fishers seldom eat fish, Peale’s fisher is enjoying a fish.

-

Two Birds

Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). Two birds, drawn for Capt. M. Lewis, 1806. Peale-Sellers Family Collection. (Mss. B P31)

Meriwether Lewis discovered these two species of birds–a Mountain Quail and a Lewis Woodpecker–while on expedition. Specimens of the birds were brought back and given to Thomas Jefferson. He in turn gave them to the APS and Charles Willson Peale created these images from the specimens.

-

Missouri Bear

Titian Ramsay Peale (1799-1885). Missouri Bear, 1822. Titian Ramsay Peale Sketches. (Mss.B.P31.15d, no. 174)

Peale painted this image from a specimen brought back from an exploratory expedition by Zebulon Pike. Pike (1779-1813) was an explorer and soldier, most often remembered for his two expeditions to the newly-acquired Louisiana territory–a venture to the source of the Mississippi River in 1805, and an exploration of the Arkansas and Red River headwaters in 1806. The bear likely came from the later expedition.

-

Alligator

William Bartram (1739-1823). Alligator, n.d. Benjamin Smith Barton Papers. (Mss. B B284d)

An influential naturalist, Bartram is best known for his work Travels Through North & South Carolina, Georgia, East & West Florida... (1791). Embarking from Charleston, South Carolina in 1773, Barton undertook a four-year, 2400-mile excursion through the southeastern colonies. He described his experiences inTravels, remarking upon the animals, plants, and humans he encountered on his journey. A devout Quaker, Bartram wondered at the animals he came across: "The animal creation ... excites our admiration." He observed numerous alligators on his travels, and wrote vivid descriptions of what he saw:

Behold him rushing forth from the flags and reeds. His enormous body swells. His plaited tail brandished high, floats upon the lake. The waters like a cataract descend from his opening jaws. Clouds of smoke issue from his dilated nostrils. The earth trembles with his thunder. When immediately from the opposite coast of the lagoon, emerges from the deep his rival champion. They suddenly dart upon each other. The boiling surface of the lake marks their rapid course, and a terrific conflict commences. They now sink to the bottom folded together in horrid wreaths. The water becomes thick and discoloured. Again they rise, their jaws clap together, re-echoing through the deep surrounding forests. Again they sink, when the contest ends at the muddy bottom of the lake, and the vanquished makes a hazardous escape, hiding himself in the muddy turbulent waters and sedge on a distant shore. The proud victor exulting returns to the place of action. The shores and forests resound his dreadful roar, together with the triumphing shouts of the plaited tribes around, witnesses of the horrid combat. (Bartram, Travels, page 118).

-

Sandhill Cranes

Titian Ramsay Peale (1799-1885). Sandhill Cranes, [1820]. Titian Ramsay Peale Sketches. (Mss.B.P31.15d, no. 88)

In 1819 Titian Ramsay Peale joined Major Stephen Harriman Long’s Scientific Expedition as zoologist, painter and as assistant naturalist. This painting was made from sketches Peale made in the field while at the expedition’s winter quarters at Engineer Cantonment, in present-day Nebraska.

-

Vocabularies

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), Comparative vocabularies of several Indian languages, 1802-1808. (Mss. 497 J35)

Jefferson, a passionate collector of information on Native American languages and culture, thought that intense study of such material would reveal the origin of the Native Americans and, ultimately, of the human race. This page is just one of a larger vocabulary. Unfortunately, Jefferson’s work was vandalized during a crossing of the James River. A hooligan ransacked Jefferson’s papers and threw them overboard. The page shown here is among the few that were recovered after being washed ashore.

-

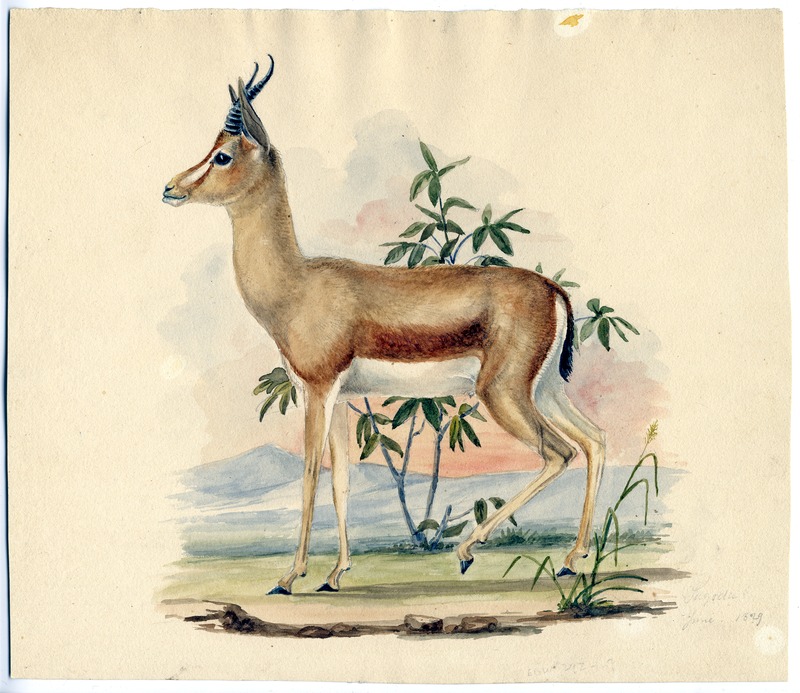

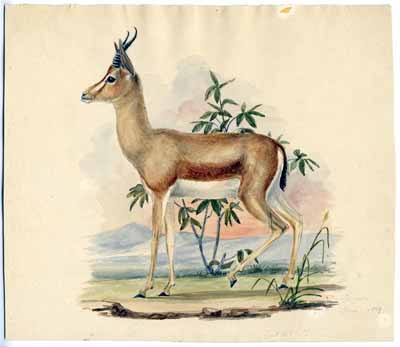

Antelope

Titian Ramsay Peale (1799-1885). Antelope (Gazelle), 1829. Titian Ramsay Peale Sketches. (Mss.B.P31.15d, no. 194a)

Despite being labeled "Antelope" by Peale, the animal depicted here is a pronghorn. Indigenous to western and central North America, pronghorns are incredibly fast animals which can reach speeds up to 55 miles per hour. The pronghorn was encountered in South Dakota by the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Meriwether Lewis recorded the following in his journal on 17 September 1804:

I had this day an opportunity of witnessing the agility and superior fleetness of this animal which was to me really astonishing... I got within about 200 paces of them when they smelt me and fled...So soon had these antelopes gained the distance at which they had again appeared to my view I doubted at first that they were the same that I had just surprised, but my doubts soon vanished when I beheld the rapidity of their flight along the ridge before me it appeared rather the rapid flight of birds than the motion of quadrupeds. I think I can safely venture the assertion that the speed of this animal is equal if not superior to that of the finest blooded courser.

Rabbit

Titian Ramsay Peale (1799-1885). Rabbit, Lepus palustris, [1836]. Titian Ramsay Peale Sketches. (Mss.B.P31.15d, no. 244)

The animal depicted here is a Marsh Hare, which is native to the coastal areas of the southeastern United States. Peale notes that this particular animal was found in South Carolina. Marsh Hares are excellent swimmers and are unusual for rabbits in that they often walk on all fours, much like a cat. The marshland they frequent contains dense vegetation, where walking is more advantageous than hopping.

-

White Salmon Trout

Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809), White salmon trout, 1806. Lewis and Clark Journals, Codex J. (Mss. 917.3 L58)

In his instructions to Captain Meriwether Lewis in 1803, Thomas Jefferson wrote that "your observations are to be taken with great pains & accuracy, to be entered distinctly and intelligibly for others as well as yourself." The original journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition are in the possession of the APS, where they have been preserved since their donation by Thomas Jefferson and Nicholas Biddle in 1817 and 1818.

-

Jefferson Letter

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) to John Vaughan, Autographed letter signed, 15 August 1805. APS Archives. (APS Archives III, 1)

In this letter, Jefferson refers to the Megalonyx, which he believed to be a giant tiger which still stalked the American wilderness. In fact, he had been studying the fossilized remains of a long-extinct creature which was not a tiger, but a giant sloth! Despite the misidentification, Jefferson is credited with being the "Father of American Paleontology" for his work with the Megalonyx’s fossilized bones.