Behind-the-Scenes of the Dr. Franklin, Citizen Scientist Virtual Tour

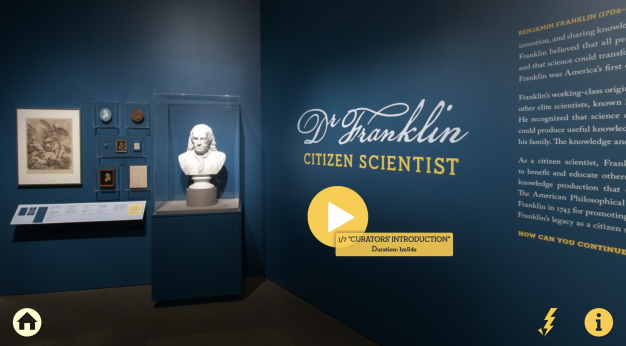

When the pandemic forced the American Philosophical Society (APS) to close, our upcoming exhibition, Dr. Franklin, Citizen Scientist, was on the verge of installation. Thanks to an NEH CARES grant, along with the help of Greenhouse Media, we were able to produce a virtual tour of the exhibition that allows viewers at home to move through the exhibition gallery, watch short videos that expand on the exhibition’s themes, and see selected object highlights. We approached the virtual tour as we would an in-person tour––with a more casual voice than the exhibition texts, a focus on narrative themes, and by focusing on a few objects.

Over the summer, Emily Margolis (co-curator) and I began preparing for the virtual tour by writing short video scripts that covered specific themes in the exhibition. We decided to film 7 videos for the adult tour, each about 2 minutes long. Our Museum Education colleagues, Michael Madeja and Alexandra Rospond, reviewed our scripts. We did our best to memorize the content and we practiced our delivery via Zoom meetings.

Once the exhibition was fully installed, Greenhouse Media filmed Emily and I in the gallery. It was a fun day of filming. We did our best to remain socially-distanced and everyone wore masks. The only time we took our masks off was when we were actively filming. Greenhouse Media also did panoramic photography of the gallery.

Emily and I also chose objects to highlight in the virtual tour. This was really hard––there are 92 individual objects in the exhibition and we could only highlight 30! We thought that 30 would be enough to tell the exhibition’s narrative without becoming overwhelming. We did our best to choose objects that best exemplified the exhibition’s themes and we chose a few that were personal favorites.

Then we got to write brand new texts to accompany the object highlights. Our in-gallery object labels are limited to about 30-40 words. The virtual format allowed us to expand our interpretations of the objects and share a few fun facts and insights that do not appear in the physical exhibition space. Some of the information we included is the type of information that we would share if we gave an in-person tour of the exhibition––interesting facts and observations that are not integral to the exhibition’s narrative but are fun to point out. Therefore, the labels in the virtual tour are related to, but different from the labels hanging in the gallery. So, if you are really interested in the exhibition and want to read all the texts that Emily and I wrote, be sure to check out the exhibition in-person when it opens next year and the exhibition catalog, which will be released online for free download next month.

Though the exhibition was developed in 2019 and was essentially finished by March 2020, current events affected both the objects we chose to highlight and the additional texts we prepared over the summer. For example, the essay that Benjamin Franklin wrote promoting the public health benefits of smallpox inoculation felt more relevant than ever. Obviously, vaccinations and public health measures are in the daily news. But the fact that Onesimus, an enslaved man, first introduced the West African medical practice of inoculation to Bostonians also resonated with current discussions about racial inequality. Franklin did not acknowledge Onesimus’s role in his essay, instead giving credit for inoculation’s success to a white doctor. As Americans grapple with the role of slavery and racism in U.S. history, the story of smallpox inoculation is one that allows us to discuss the ways Black people have been obscured in archives, how Black people have shaped history in important ways, and the long entanglement of racism and public health.

Once all the filming, photography, and texts were complete, we continued to communicate with Greenhouse Media who produced the tour for us. The APS exhibition team reviewed demo versions of the virtual tour. We also gave feedback on every element, including what the video icons should look like, the font that should be used, and what the primary views are when you click to move to the next section of the gallery.

We also had the opportunity to put together a tour specifically for a younger audience, which was especially important to us with so many students relying on virtual resources these days. Emily and I advised and offered feedback, but the tour was largely developed by our Museum Education colleagues. The Youth Tour has fewer highlights and videos. The Education team chose to highlight some different objects than Emily and I did for the Adult Tour. I highly recommend that adults also check out the Youth Tour to see some different objects highlighted.

To learn more about the development of the Youth Tour, check out this blog post by my colleague, Michael Madeja. Visit both the virtual tour(s) here.

The exhibition team for Dr. Franklin, Citizen Scientist consisted of:

Janine Yorimoto Boldt, 2018-2020 Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow

Emily A. Margolis, 2019-2021 Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow

Mary Grace Wahl, Associate Director for Collections and Exhibitions

Michael Madeja, Head of Education Programs

Alexandra Rospond, Museum Education Coordinator

Magdalena Hoot, Curatorial Assistant

Special thanks to David O. McCullough, Christine Freije, and Grant Struble for their feedback on the content.

This project has been made possible in part by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities: Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act.

Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this blog do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.