Spurious Sexploits: The Case of the James Wilson Diary

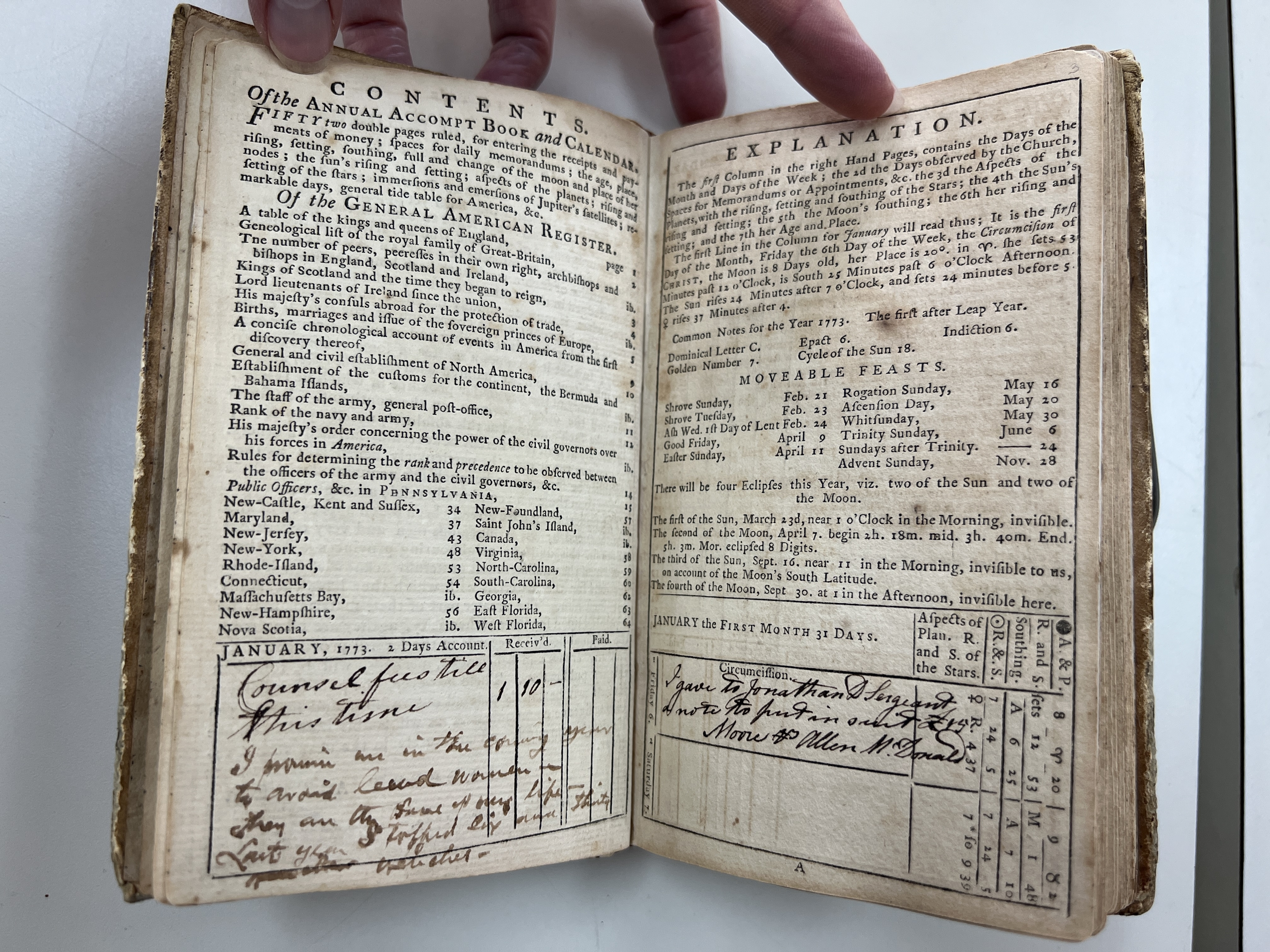

In 1956, the American Philosophical Society acquired a 1773 almanac that had been used as an account book and diary by James Wilson (1742-1798, APS 1768), a lawyer who was twice elected to the Continental Congress and who signed both the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution. His diary entries (short, and in a dark brown ink) detail his trips to courthouses in Trenton, Easton, Carlisle, and Reading, and his expenses for food, wine, ink powder, and clothes. He engaged tradesmen to cut wood and sharpen razors, and he gambled regularly, purchasing lottery tickets with friends and losing money steadily at whist. A second set of entries in lighter brown ink, however, has long titillated historians. These entries contain lengthier descriptions of sexual encounters (some consensual, some not) and their repercussions for the unidentified writer. When were they written? And did they have any basis in fact?

This year, I undertook conservation treatment for the dilapidated diary, in part to characterize the second manuscript ink as either historical (contemporary with the 18th century) or a modern forgery. Iron gall ink was the only black ink used for manuscripts during the time covered by Wilson’s diary (1773-1786), although carbon-based black inks were used in artworks. Iron gall ink is made by adding ferrous sulfate to a tincture of crushed oak galls. It is acidic, etches the surface of the paper, and typically turns brown with age.

In general, iron gall ink can be detected by using bathophenanthroline test strips, which contain a non-bleeding dye that turns pink or magenta in the presence of iron(II) ions. I used these strips to test six different entries in James Wilson’s hand from locations throughout the diary. Three were written in his usual dark brown ink, and three were in a pale, washy ink (albeit a cool gray-brown rather than the warm red-brown used by the second writer). After the dampened strips were pressed to the inks for 30 seconds, they turned magenta in scattered areas, confirming the presence of iron gall ink.

The ink used to describe sexual exploits caused no reaction in the bathophenanthroline test strips. While it is possible that the pale red-brown ink is an iron gall ink that lacks excess iron(II) ions, such inks are exceedingly rare. Visually, the ink looks more like an aged red ink, like those used for ruling account books during the period. Such red inks were traditionally made with logwood, vinegar, and alum, and would not be expected to react with bathophenanthroline test strips. A modern brown dye-based ink might also have this appearance—and it would probably fade after application.

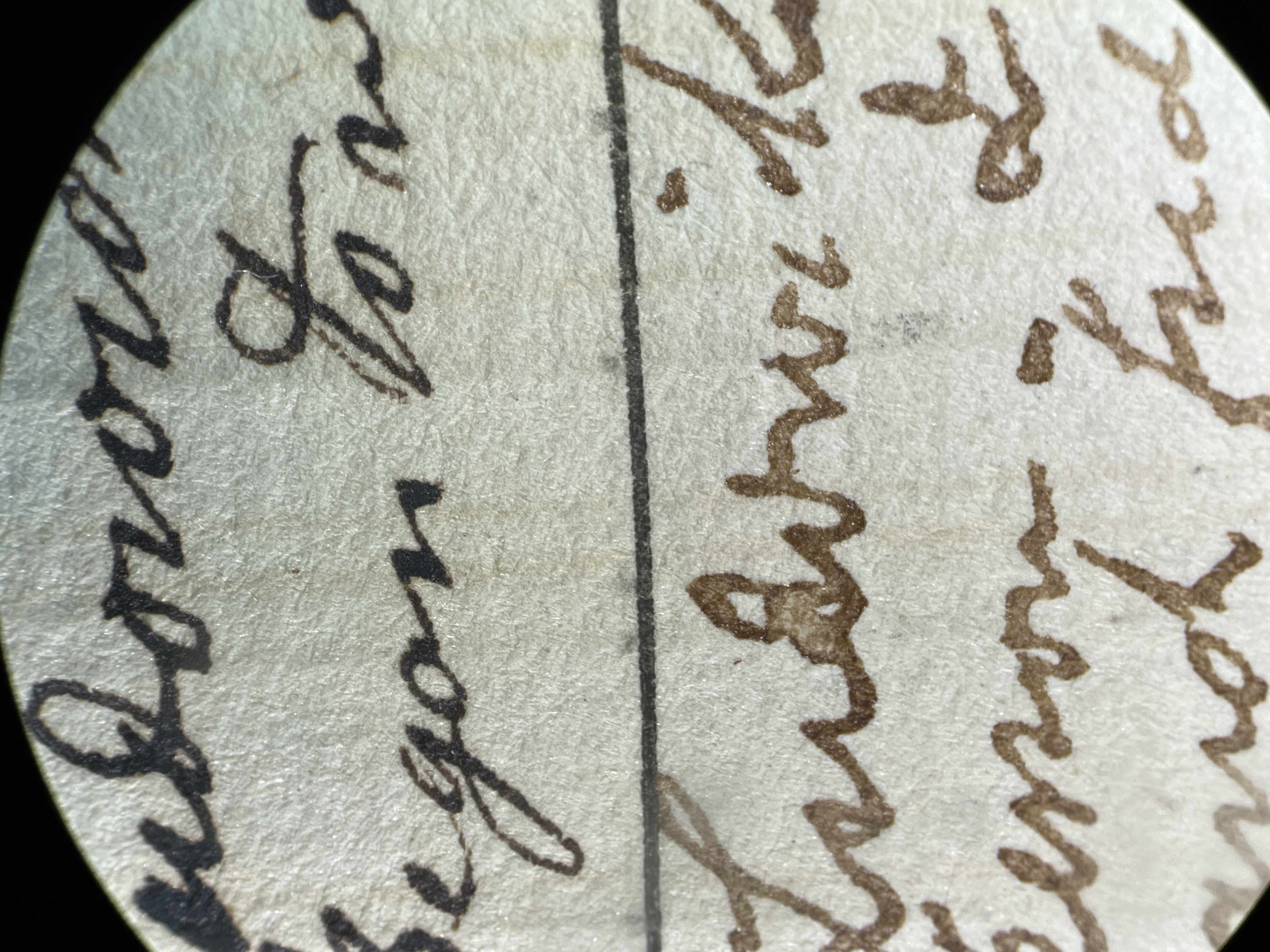

Looking at the inks under a powerful stereomicroscope provided additional evidence that the pale ink was a later addition, or fake. Wilson’s entries looked like normal iron gall ink under magnification: the ink was opaque, with a dark brown, shiny, rough surface due to the iron-based pigment particles trapped in the ink binder. The pale brown ink from the sexual entries was washy, translucent, smooth, and contained no pigment particles. The ink strokes were darker at the edges, where the ink had pooled and evaporated. Where it was heavily applied, the ink was shiny; in other places, it was matte.

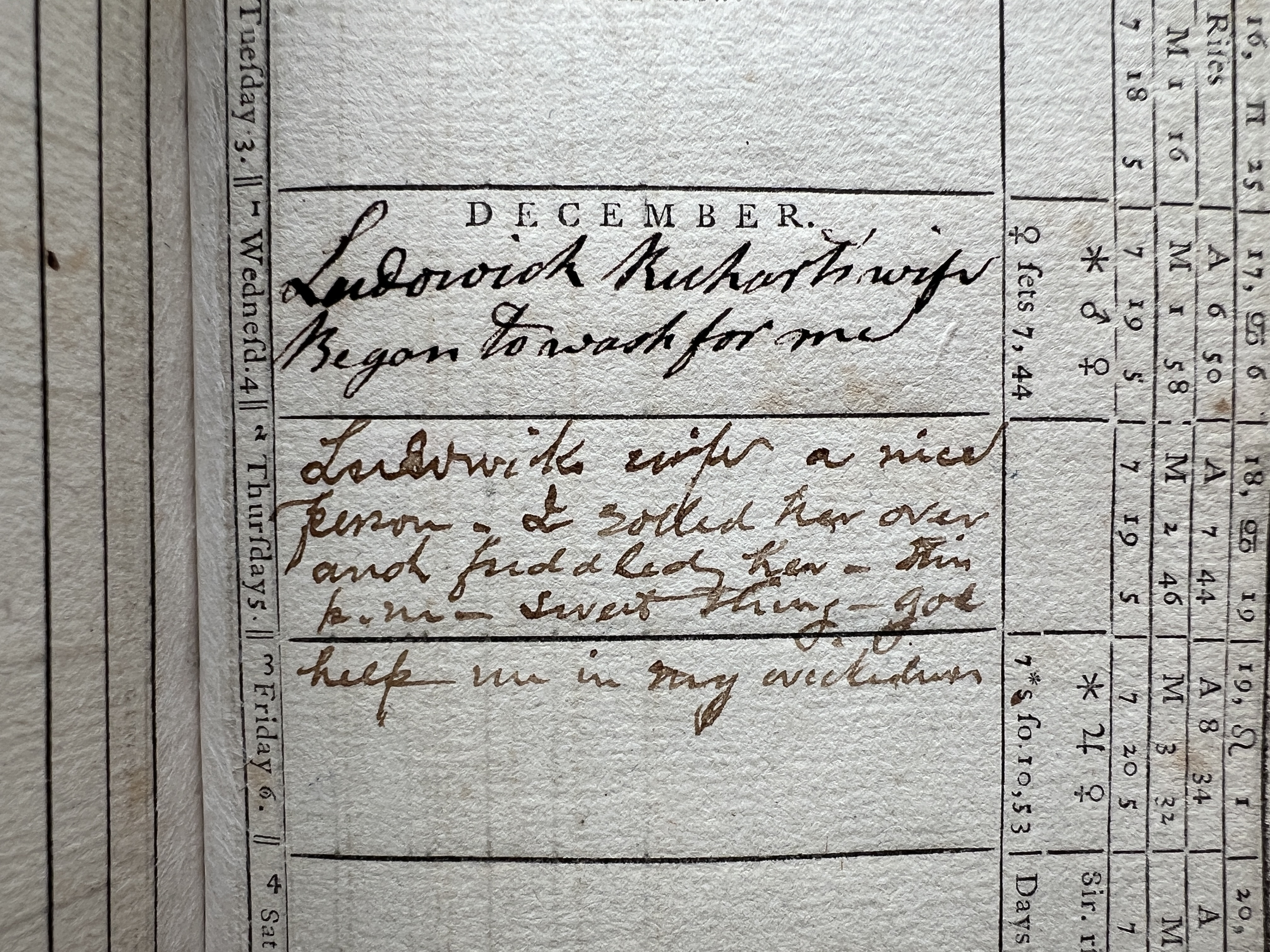

Given these differences, the light brown ink is probably a modern fake, intended to deceive the reader and impugn Wilson’s character. One passage is particularly suspicious. In the space dedicated to Wednesday, December 4, Wilson wrote “Ludowick Richart’s wife Began to wash for me” in his usual dark brown ink. In the space immediately below, for Thursday, December 5, the paler ink continued, “Ludowicks wife a nice person – I rolled her over and fuddled her – This p.m – sweet thing – god help me in my wickedness.” The content of the two entries is clearly intended to fool a reader into thinking they were written by the same person. The lower-case spelling of “god,” the use of “nice” in the sense of “kind” rather than “foolish,” and the absence of a long S in “wickedness” may all indicate a modern forger. Why this forger wished to present James Wilson as a satyr is another question entirely.