An Extraordinary Eccentric Woman: Madame de Staël

Header Image: Anne Louise Germaine Necker, Baroness of Staël-Holstein (known as Madame de Staël) c.1815-7, by Joseph Bouton. Royal Collection Trust.

Anne Louise Germaine de Staël, more commonly known as Madame de Staël, is a fascinating figure whose intellectual community spanned from socializing with the Founding Fathers as a child to helping introduce the Germanic literary movement to England and France. The American Philosophical Society has a few materials directly relating to de Staël, as well as several letters regarding her husband’s work as an ambassador with Benjamin Franklin on behalf of the King of Sweden to recognize the United States.

De Staël was born in April 1766 to Jacques Necker, a Genevan banker who rose to Director-General of Louis XVI’s treasury, and Suzane Necker (née Curchod), salonnière and founder of the Necker-Enfants Malades Hospital. Germaine de Staël’s childhood and teenage years were spent attending her mother’s salon, which was considered one of the era’s most prestigious. It was there that de Staël met intellectuals from all over Europe and the American colonies, including Benjamin Franklin. De Staël’s mother insisted on a rigorous education based on Rousseauian principles, which influenced her later writings and political beliefs.

When de Staël was 20, she married Baron Erik Magnus Staël von Holstein, the Swedish ambassador to France. Through her marriage to an ambassador, she received protections which allowed her to host her own salons during the social unrest that accompanied the outbreak of the French Revolution. Thomas Jefferson (APS 1780) and Gouverneur Morris attended these salons, alongside French political figures such as Talleyrand and Antoine Barnave. The marriage itself was not a passionate one, and de Staël took lovers outside of her marriage. Baron de Staël died in 1802; Madame de Staël married Albert Jean Michel de Rocca in 1816 after giving birth to their son in 1812. She was also in a long term relationship with Benjamin Constant, and her daughter, Albertine (1797–1838), was thought to have been a product of their relationship.

After the outbreak of The Terror in 1792, wherein de Staël was brought before Robespierre on the first day of the September Massacres, she was escorted out of Paris and subsequently fled to her parent’s home at Coppet, in Switzerland. There and also at Juniper Hall in England, where she was a part of the French émigré society for four months before returning to Switzerland, de Staël continued to write and socialize with other intellectuals and politicians. By 1797, de Staël returned to Paris and reopened her salon there.

Through her friendship with Talleyrand, de Staël met Napoleon Boneparte. The two maintained animosity towards each other; De Staël believed in transitioning France to a constitutional monarchy like England. She also identified Napoleon’s attitude and aims as tyrannical and felt he was antagonistic towards women in the public intellectual sphere–especially those who were against his Continental plan. Eventually this led to Napoleon exiling de Staël from the area in and around Paris for ten years starting in 1803; she and her family traveled from France to Germany and then back to Coppet after the death of her father in 1804. Juliette Récamier, another famed salonnière and critic of Napoleon, was one of de Staël’s closest friends and stayed with her at Coppet while seeking a divorce from her husband; Napoleon banished her while Récamier traveled to her friend’s home. De Staël is quoted as saying in reply to Bonaparte at the news of her own exile that, “You are giving me a cruel celebrity; I will occupy a line in your history”.

By 1814, de Staël had spent time living in Switzerland, France, and traveling throughout Eastern Europe. It was during an 1814 visit to London that de Staël met English abolitionist William Wilberforce and subsequently spent the rest of her life an advocate for the abolition of slavery. She died on July 14, 1817, leaving behind a wealth of writings, including the bestselling 1812 novel Delphine and the 1813 seminal literary work D’Allemagne, which introduced German Romanticism to the rest of Europe.

Included in the materials at APS is a letter from de Staël to statesman Benjamin Vaughan, who had settled in Maine after fleeing Britain in 1794 due to accusations of treason and conspiracy of a French invasion. Vaughan defended slavery as a cultural institution of the West Indies, as his family fortune came from owning people and plantations in Jamaica. His later support of abolition was more as a way to appease enslaved people and avoid a situation similar to the Haitian Revolution.

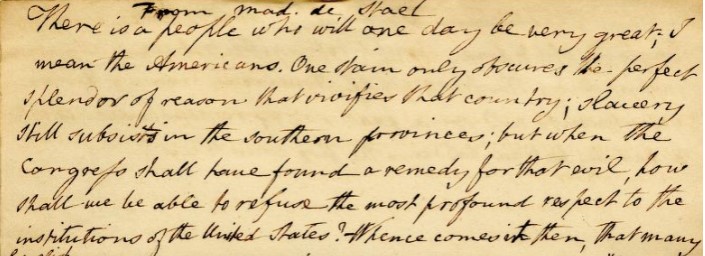

The letter opens with, “There is a people who will one day be very great; I mean the Americans. One stain only obscures the perfect splendor of reason that rarifies that country; slavery still subsists in the southern provinces; but when Congress shall have found a remedy for that evil, how shall we be able to refuse the most profound respect to the institutions of the United States?” She then goes on to condemn the British for burning “peaceful edifices, sacred to national representation, to public instruction, to the transplantation of arts and sciences” in Washington, D.C., which dates this letter most likely in the fall or winter of 1814.

Other materials relating to de Staël at the APS include an 1805 letter from Wilhelm Humboldt to Giovanni Fabronni in Italian [Giovanni Valentino Mattia Fabbroni papers, Mss.B.F113] and an undated letter from philosopher Destutt de Tracy to architect Leon Duforny about a dinner with de Staël and either German poet August Schlegel [Athénée des arts de Paris letters, Mss.506.44.At4]. The APS also has copies of de Staël’s 1813 pamphlet Appeal to the nations of Europe against the continental system [Pam. v.66, no.6] and her posthumously published work, the 1818 Considerations on the principal events of the French Revolution [PNE 68 St1c v.1, 2].