For Thomas Jefferson, science and politics existed side by side, each illuminating the other. From his interest in mastodons to his deep interest in the culture, languages, and political status of Native Americans, his scientific studies played a role in conceptualizing and building a new political order in America that was distinct from and superior to the political systems of the old world.

For Thomas Jefferson, science and politics existed side by side, each illuminating the other. From his interest in mastodons to his deep interest in the culture, languages, and political status of Native Americans, his scientific studies played a role in conceptualizing and building a new political order in America that was distinct from and superior to the political systems of the old world.

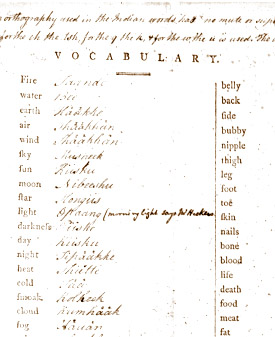

In the 1780s, Jefferson began to entertain the notion of using languages to unravel the complex relations between the Indian tribes and nations inhabiting North America. As outlined in his Notes of the State of Virginia (Paris, 1782), he theorized that American Indians had migrated from Asia into this continent over the Bering Straits (or perhaps, he added, they had migrated from America), and had subsequently broken into many small political units. A comparative study of Indian languages, he thought, "would be the most certain evidence" for this theory of American Indian origins, and might even constitute "the best proof of the affinity of nations which could be produced."

His proposal was predicated on the belief that languages have histories that uniquely reflect the political and social histories of the populations that speak them. Common vocabulary and common "principles of regimen and concord" among them mirror the fates of nations as they separate and diverge: the more recent the break, the more similar the language. Some languages will be nearly identical, having arisen only recently, while others will bear but faint traces of their former connections. Were enough vocabularies from enough Indian languages gathered, Jefferson suggested, the entire prehistory of the peopling of the North American continent could be reconstructed.

Such thought about the fate of nations was integral to Jefferson's political theories. Indians, he suggested, had once comprised a single nation, but not being governed by the rule of law or by "any coercive power, any shadow of government," they fragmented politically -- a palpable fear for many during the period of Confederation. Only the innate sense of right and wrong shared by all humans restrained Indians from committing evil acts, and living in their natural state, he observed, Indians committed few crimes indeed. In contrast, Europeans, governed by too much law and too much coercion, were prone to lose their civic virtue and were capable of committing great evils. "The sheep are happier of themselves," Jefferson concluded, "than under care of the wolves." An analysis of Indian languages, then, promised to contribute to creating the ideal form of government, neither too little, nor too much law.