of the Declaration of Independence

Three Declarations of Independence, 1776

Yet as much as the APS was tested in the century's greatest political conflict, the members who remained played a uniquely important role in helping to shape the course of events. From Franklin and Jefferson, to Adams, Washington, and Lafayette, many of the luminaries in the Revolutionary cause became deeply attached to the Society, and as a result, the collections of the APS took on a distinctly revolutionary cast. Nowhere is this history better reflected than in three of its best known items, remarkable copies of that seminal revolutionary document, the Declaration of Independence.

Many of the most dramatic scenes of the independence movement were played out within two blocks of the current home of the APS, from the drafting of the Declaration, to its ratification and distribution. Four of the five members of the drafting committee would become members of the Society, including the two most important, Jefferson and Franklin (Roger Sherman was the exception), and perhaps more impressively, fifteen members signed the Declaration. In more obscure ways, too, the APS contributed to the revolutionary platform -- in one case, physically. When the Declaration was read publicly in the State House yard on July 8th, 1776, John Nixon stood on a platform that had been erected by the APS for David Rittenhouse to observe the transit of Venus in 1769. As it was read, the crowd cheered and the King's arms were torn down from the State House. That evening, all across the city, bonfires blazed amid the pealing bells and "other great Demonstrations of Joy."

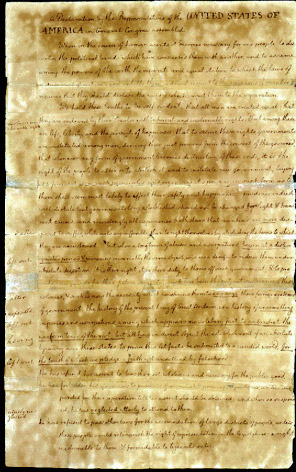

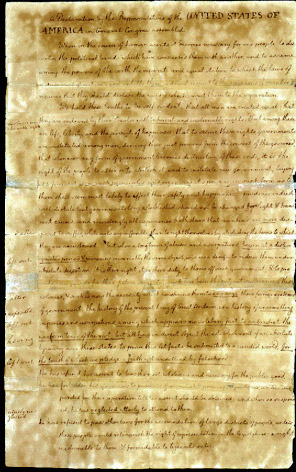

The Jefferson draft

|

of the Declaration of Independence |

Jefferson's draft of the Declaration was donated to the APS on August 19, 1825, by Richard Henry Lee, Jr., the grandson of Jefferson's friend. Both leaves of the document were set between panes of glass before 1840, sealed with a wax-impregnated cloth tape, and mounted in a wooden frame for public display. For many years, the draft was placed in the window of the Society for public viewing, in the process, sustaining damage through exposure to the sun and fluctuations in temperature and humidity. The document was removed, and "repaired" with small strips of "transparent" paper in 1898, but was again consigned to the frame. The photograph at left represents the document as it appeared in 1998, immediately prior to the most recent conservation work funded by the Pew Foundation.

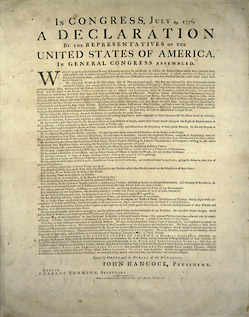

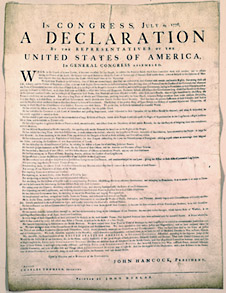

John Dunlap's first printing

Having been thoroughly vetted among the members of Congress during the debates of July 2nd and 3rd, the Declaration of Independence was formally approved during the momentous session of July 4th. That afternoon, a copy was rushed to the print shop of John Dunlap on Market Street, and that night, the type was set for the first printing. It was quick work, indeed. By the morning, a stack of copies was delivered to the waiting delegates in the State House, and others were prepared to be sent for public reading to each of the state assemblies and to the various committees of safety, as well as to the commanding officers of the Continental troops. It was a copy similar to this one that John Nixon read aloud in the State House yard on the 8th.

Having been thoroughly vetted among the members of Congress during the debates of July 2nd and 3rd, the Declaration of Independence was formally approved during the momentous session of July 4th. That afternoon, a copy was rushed to the print shop of John Dunlap on Market Street, and that night, the type was set for the first printing. It was quick work, indeed. By the morning, a stack of copies was delivered to the waiting delegates in the State House, and others were prepared to be sent for public reading to each of the state assemblies and to the various committees of safety, as well as to the commanding officers of the Continental troops. It was a copy similar to this one that John Nixon read aloud in the State House yard on the 8th.

Although the original number printed is unknown, fewer than 25 copies survive. This fairly healthy number probably reflects the great importance that was almost immediately attached to the document, as well as its official nature. The APS copy of Dunlap's first edition of the Declaration was acquired in 1901 in an exchange of duplicate materials with the Library of Congress. In return, the Library of Congress received a copy of Franklin's famous hoax, Supplement to the Boston Independent Chronicle, no. 705, of March 12, 1782.

John Dunlap's printing on vellum

Although the first printing of the Declaration is among the best known of all American imprints, the vellum printing is much rarer. At some time before July 19th, John Dunlap returned to his shop to reset the type for a second printing. This issue, somewhat larger in size than the first, was printed in a very small number on a more durable substrate, vellum. We can only speculate on why Dunlap went through the trouble to prepare a second edition so soon, and why he might have chosen to print on vellum. Currently, the best guess is that he, too, recognized the significance of the political act of claiming independence, and sought to create an edition that captured the momentous importance of that act in a more permanent fashion.

Although the first printing of the Declaration is among the best known of all American imprints, the vellum printing is much rarer. At some time before July 19th, John Dunlap returned to his shop to reset the type for a second printing. This issue, somewhat larger in size than the first, was printed in a very small number on a more durable substrate, vellum. We can only speculate on why Dunlap went through the trouble to prepare a second edition so soon, and why he might have chosen to print on vellum. Currently, the best guess is that he, too, recognized the significance of the political act of claiming independence, and sought to create an edition that captured the momentous importance of that act in a more permanent fashion.

A close friend of the printer, David Rittenhouse, seems to have acquired the vellum Declaration at about the time of printing. An instrument maker and astronomer, as well as the second President of the APS, Rittenhouse was an ardent patriot and an active member of the Committee of Safety during the Revolution. Clearly, Rittenhouse had both the motive and opportunity to acquire a copy of the Declaration. It descended from Rittenhouse's family to the physician, James Mease, who donated it to the Society in 1828. It is the only copy known of this printing.