What’s Happening in that Frontispiece? And What Exactly Is a Frontispiece?

By Janine Yorimoto Boldt and Emily A. Margolis

While doing research on Mesmerism (also called animal magnetism) for the exhibition Dr. Franklin, Citizen Scientist, we looked at the book L’Antimagnétisme by Jean-Jacques Paulet. Multiple people asked us if we could figure out what was happening in the frontispiece, which features a pretty strange illustration. Then, when we started writing our exhibition labels, we included the word “frontispiece” in a draft. Our education team told us that we had to avoid using the term “frontispiece” because museum visitors might not be familiar with it. Or, if we insisted on including it, we had to define it clearly. This comment resulted in a brief (good-natured) argument amongst the exhibition staff about whether or not we should use this word.

So, here we are to both define “frontispiece” and break down the iconography (use of symbols) of a particularly fascinating one.

A frontispiece is an illustration that appears facing a book’s title page. When a book is open to the title page, the frontispiece appears on the left and the title page on the right. The illustration can be purely decorative or informative, or a combination of both.

Here’s an example from Benjamin Franklin’s personal copy of Robert Boyle’s writings. The frontispiece to volume 1 is a portrait of Boyle himself.

So, what is happening in the wild illustration from L’Antimagnétisme? First, a quick note on animal magnetism, or Mesmerism. Franz Anton Mesmer (1734-1815), a German-born physician, theorized the existence of magnetic fluids in the bodies of humans and other animals (“animal magnetism”). Mesmer suggested that disease was caused by disruptions to the fluid’s flow, and developed highly-performative medical practices aimed at restoring the flow through external manipulation. You can learn more here.

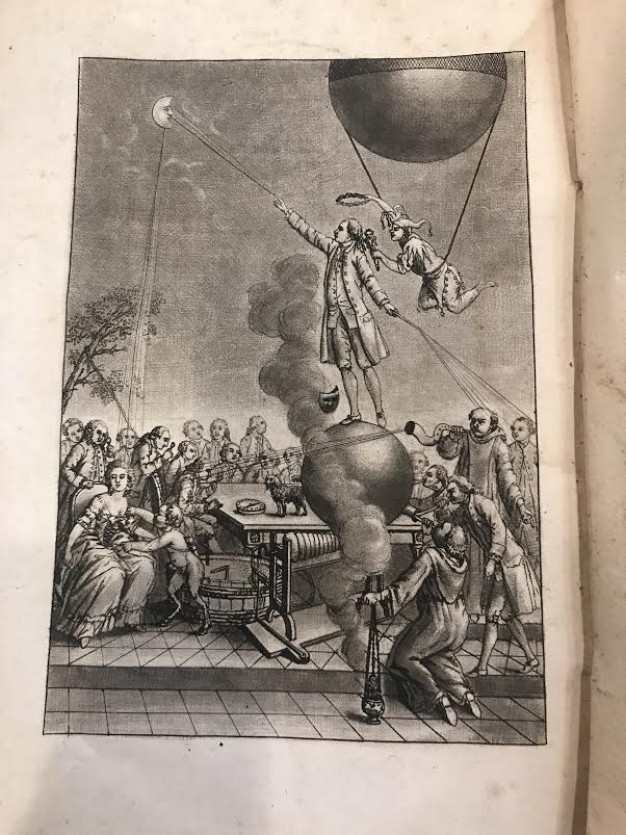

The author of L’Antimagnétisme, Paulet, was a major critic of Mesmer, writing this book to criticize him and his methods. The frontispiece mocks Mesmer’s medical performances. Mesmer is represented standing on a large ball while holding a magnetized wand and directing energy from the moon and the musical instruments towards a woman receiving treatment. The woman is half-asleep/hypnotized with her eyes closed. That she is surrounded by men underscores the eroticism associated with Mesmer’s treatments.

Here’s a breakdown of the rest of the illustration:

Paulet was not alone in criticizing Mesmer and his methods. King Louis XVI of France was a prominent skeptic. Reacting against the fascination of his wife, Marie Antoinette, and other courtiers, Louis XVI convened a committee of prominent scientists, including Benjamin Franklin, to “peer review” Mesmer’s claims. Franklin’s residence in Passy was the site of their 1784 investigation. They concluded that Mesmer’s treatment was ineffective, and Franklin attributed Mesmer’s popularity and relative success in “curing” patients to the power of suggestion – what doctors today call the “placebo effect.” In other words, Mesmer’s patients believed his treatments worked and therefore experienced some relief in symptoms.

Mesmerism seems pretty strange to us today. However, manipulating magnetic or electrical bodily fluids was not such a crazy idea in the 18th century. To learn more about Franklin’s experiments on the medical applications of electricity, see this earlier blog post. Although the practice of Mesmerism was discredited in its time and has since fallen out of favor, the word “mesmerize” remains a part of our modern vocabulary.