Still Ticking: A Modern Clockmaker Revives His 18th-Century Philadelphia Predecessor, in a New Biography from the APS Press

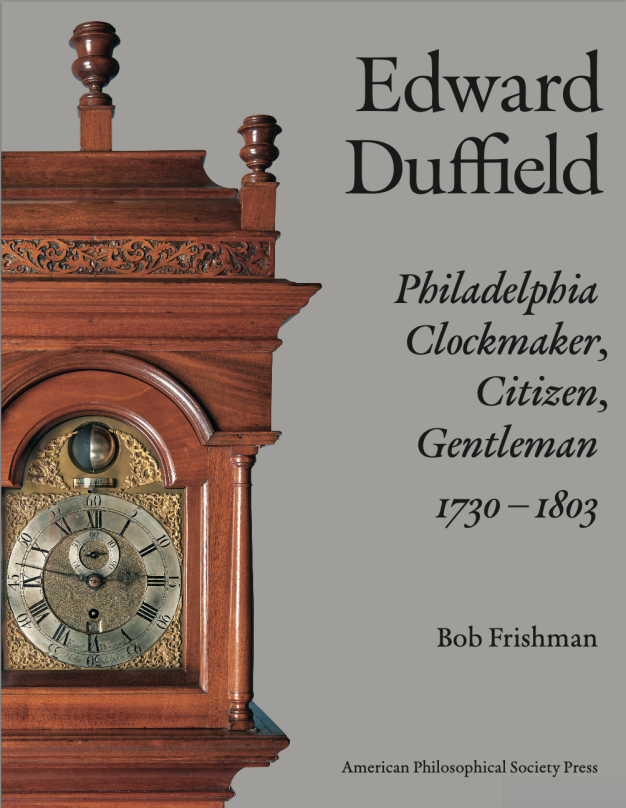

This August, the APS Press will be releasing Edward Duffield: Philadelphia Clockmaker, Citizen, Gentleman, 1730-1803, by Bob Frishman. The story of Edward Duffield’s life is both a window into the world of colonial clockmaking and a history of 18th-century Philadelphia from the perspective of one of its chief citizens. It is a story of skilled labor and intercontinental commerce, of politics and science, and of useful knowledge. As a master craftsman, Duffield spent a quarter-century constructing and repairing high-quality timepieces for wealthy clients. As a member of Philadelphia’s elite, he witnessed or participated in many major events of the Revolutionary period.

Most famously, Duffield hosted the first meeting of the Committee of Five—a group convened to draft the Declaration of Independence, which included his good friend Benjamin Franklin, as well as John Adams and Thomas Jefferson—at his Benfield estate. For these sympathies, he was briefly imprisoned by the British in Philadelphia’s Walnut Street Jail during their occupation of the rebel capital.

Duffield’s horological accomplishments were publicly recognized in 1762, when he was appointed Keeper of the State House Clock in Philadelphia (now Independence Hall), and again in 1768, when he was elected to the APS and asked to construct a high-accuracy clock to time the Transit of Mercury the next year. The master clockmaker supplied the latter device in under three weeks.

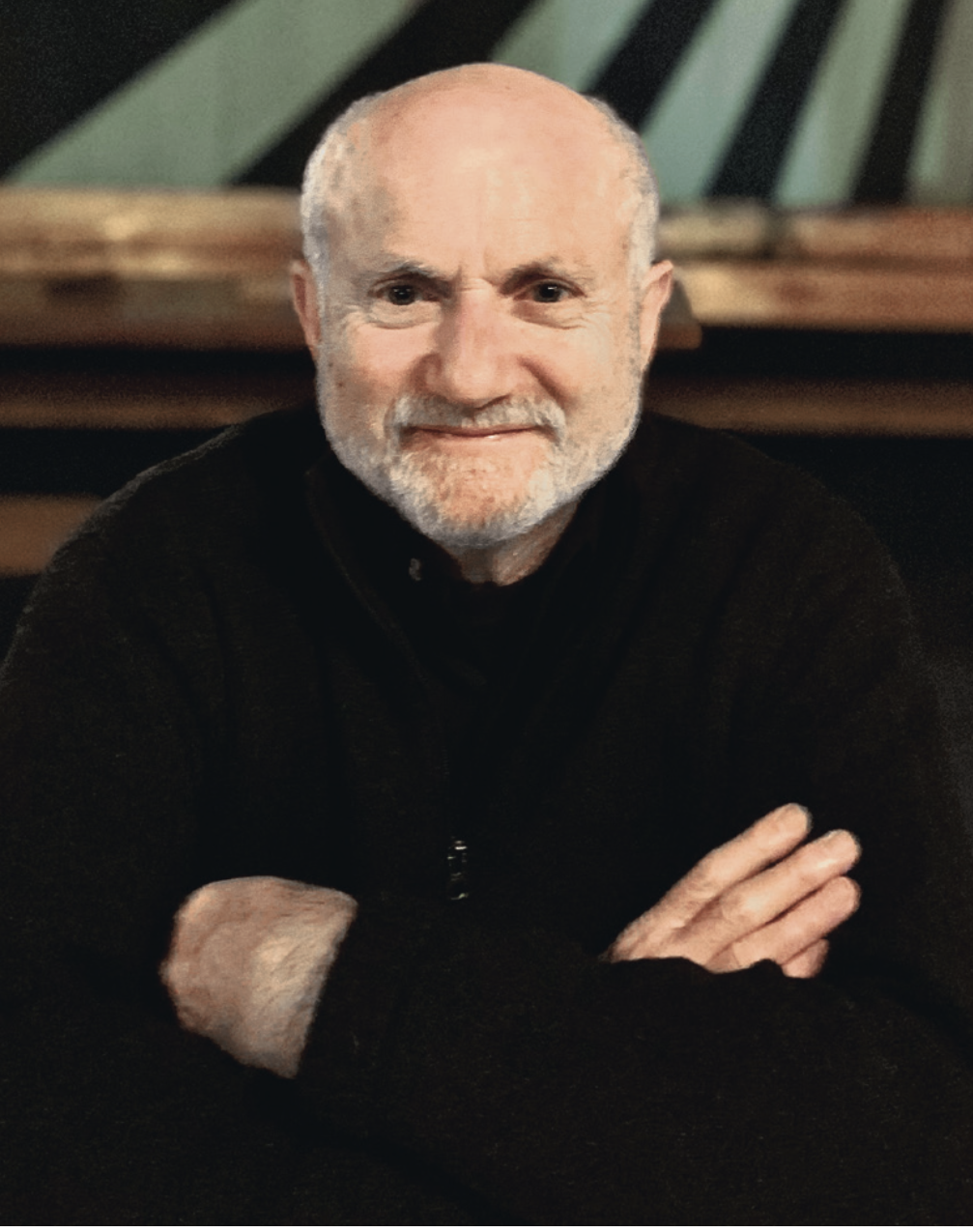

I spent a day with Duffield’s biographer, Bob Frishman, who is himself a noted horologist, scholar, and professional repairer of antique clocks. He is uniquely qualified to speak to both the historical context and technical content of Duffield’s life and work. I drove up to Bob’s Massachusetts home and workshop (like many a colonial artisan, he operates out of his residence) on a Monday morning in June. As expected, the gorgeous house is filled with even more gorgeous antiques: furniture, folk-art, and timepieces. Two standing clocks in seven or eight-foot cases greet us as soon we enter, and Bob leads me past hanging pendulum clocks, mantle clocks, a beautiful French timekeeper with exposed gears, a display case of finely wrought pocket-watches, and finally a relatively new addition to his personal collection: an Edward Duffield standing clock, inscribed with the maker’s name on its face. Bob got a tip before it hit the open market. Before you ask: No, there are no cuckoo-clocks.

Since opening his shop in the early 1990s, Bob has repaired over 8,000 antique timepieces and accumulated a library of nearly 1,000 books on horology. I, on the other hand, do not own a watch and have injured myself multiple times while building IKEA furniture. Luckily for me, Bob has plenty of experience explaining his trade to the uninitiated.

“This business is about relationships,” he says. “People are trusting you with their family heirlooms and their valuable purchases. You need to explain what you’re doing in a way that puts them at ease. I want everyone who comes in here to understand their own clocks better when they walk out.” He is now semi-retired from full-time repair work, and devotes most of his energy these days to writing and lecturing.

Bob is a story-teller, but he never sacrifices accuracy and precision for the sake of a good story. He learned this skill in a past life, working as a legislative aide and speechwriter on Capitol Hill, most notably for Representative Shirley Chisholm. During that time, he got interested in another form of high-precision engineering: sports cars. For better or worse, cars remained a hobby, and clocks became a full-time job. “Your hands get less dirty.”

When the first-floor tour is complete, Bob takes me down into the basement, where his workbench is set up. Dozens of gears and parts are carefully arranged there, glinting under the lamp. These are the components of a “movement,” the heart of the clock that gets hidden behind the face and within the cabinet under normal circumstances. “The dial and the case are almost always made by someone other than the clockmaker,” Bob says. “Even clock collectors are often afraid of the machinery inside, though this is by far the most interesting part.” He shows me an assembled movement of about the same size and age as the disassembled one on the bench. “After a while, you get a feel for how things fit together.”

A broken clock is not like a stalled car. When a modern car breaks down, the mechanic can plug it into a computer and determine the source of the problem within seconds. The only way to find out what’s wrong with an antique clock is to study it slowly and closely, and then take it apart piece by piece, examine each individual part (of which there can be dozens), find the problem, address it, and then reassemble the device without breaking anything else. If you’re lucky, the clock will run after you’ve done all this. Bob’s mentor liked to tell him, “You’ll know you’re getting good when you can fix your own mistakes.” “How long does that take?” “About ten years.”

“Usually, the clocks that come into my shop aren’t exactly ‘broken.’ You rarely find a crack in the gears or a snapped-off tooth unless somebody’s grandkid knocked the whole thing over. This is a machine like your car. It needs to be serviced, and if you don’t service it, it will stop working. Clocks get dusty, the dust gets in and the parts get worn. That’s why you’re supposed to have them serviced every ten or fifteen years, cleaned and lubricated. That would have been common knowledge a few generations ago, but it just doesn’t occur to a lot of folks today. So these clocks sit around and collect dust for decades, until things inside wear down so far that they can’t turn properly anymore and the ticking stops.”

“So these clocks have their original gears?”

“Yes, almost always. Now, if you told Edward Duffield that some guy in 2024 would still be using a clock he made in the 1760s, he’d laugh in your face. They were built to last, but nobody could have anticipated they would last this long. Duffield would have expected superior technology to come around at some point and replace his own. These were considered appliances, albeit appliances that doubled as status symbols, more than they were seen as art objects. Fancy refrigerators. Clocks were like that.”

I ask Bob about the most gratifying fix he’s ever pulled off.

“I do a lot of pro bono work now with museums and historical societies, fixing their clocks, researching the makers, giving lectures. I enjoy that a lot because I can work at my own pace and educate people in the process.” He pauses for a moment. “One story comes to mind. I once had a private client who came in with a clock handed down from her grandmother. I fixed it—it wasn’t a particularly difficult job—and she came back to pick it up. While she was writing the check, she heard it chime for the first time and burst into tears.”

As if on cue, the clocks in Bob’s house strike the hours immediately after he tells this story. I can hear them on the recording I took of our interview. It’s a surprisingly gentle sound, less like a school bell and more like a bird cooing—or, in this case, a flock of birds. They are all, of course, right on time.

There is an extraordinary appendix towards the end of Edward Duffield: Philadelphia Clockmaker, a reprint from an 1837 article by the horologist Edward Dent. It lists all the individual parts contained in a single pocket watch and all the laborers and craftsmen involved in their production, from raw materials harvested at the beginning of the process to the watch-maker at the end. All together, Dent counts 992 parts and 43 “artificers employed to create them.” I ask Bob to take me through the life-cycle of a clock’s fabrication from this period. How many different pairs of hands would have touched these materials before they came together in Duffield’s Philadelphia shop?

“First of all, I’m glad you brought up that appendix, because it almost didn’t make the final book. But I thought it was important to include, because the question of labor, and the division of labor, is at the heart of 18th-century horology. There’s a popular myth that I hope this book does some work to dispel: the nostalgic image of a lonely clockmaker in his workshop, fashioning every part by hand. That would have been nearly impossible in the 18th-century, but it persists because it’s quite romantic, in its way. In reality, most of Duffield’s rough movements and parts probably came from England, and then were finished and assembled in his shop.”

Bob gathers his thoughts and continues: “These are highly complex and precise machines. The teeth on these gears mesh almost perfectly. To get to that point, the whole clockmaking process—designs, movements, production, division of labor—had been standardized for nearly a century. It wouldn’t make any economic sense for a clockmaker to produce them all himself in a place like Philadelphia. Laborers in England fashioned the parts out of raw materials from various sources, and shipped them across the Atlantic. Clockmakers did not typically melt the brass or form the steel themselves, especially not a gentleman like Duffield. He’s not going to be sweating over a hot cauldron when he can pay someone to do it. There were local braziers and gear-cutters at the time, as well as English imports available from merchants a few steps away.

“It’s possible that Duffield knew how to make a clock totally from scratch, but it’s unlikely that he actually did it. With one exception: He may have been more involved in making the parts for the Transit of Mercury clock, because it was a scientific instrument that required a higher degree of precision.”

Many individual craftsmen were involved in the production of every one of Duffield’s clocks from start to finish, and many more if you count those involved in shipping and marketing. This system allowed the colonies access to higher quality time-pieces (America did not yet have the capacity to produce parts of this caliber at scale) for lower prices (the method of British manufacture and American assemblage was cheaper than either producing the devices entirely in the colonies or shipping completed clocks from the mother country). The history of colonial horology is a global history, and each clock produced was the central node of a network of materials, laborers, and knowledges that connected not just Britain and its colonies, but the whole European continent.

Speaking of networks, I also used this opportunity to probe a bit deeper into Duffield’s connection to Franklin. How did the two men meet, and why did they become friends?

“Well first of all, family. As important as anything else was the fact that Franklin’s wife Deborah was a 50-year friend of Duffield’s mother-in-law. Just as important is the fact that the first place Franklin lived in Philadelphia, when he was just a boarder in Deborah’s house, was next door to the Duffield home. The families had a common wall between their lodgings. There were frequent, lengthy family stays between them at other properties. I hesitate to overstate their technical relationship, since Franklin was 24 years older and Duffield wasn’t a printer. But Franklin had a huge respect for artisans, for craftsmen, for tinkering and for those who tinker. It’s even possible that Franklin had a role in encouraging Duffield to take up clockmaking as a trade—rather than continuing as a young merchant selling capers and raisins.”

Before I go, Bob hands me a box filled with magazines, including some issues of horology journals from years ago. “I have duplicates of all of these, so please take them. You can read, skim, throw them out, cut them up and make them into art, whatever you like. I operated a shop out of here for a long time, and I don’t want anybody to leave my house empty-handed.”