RevolutionaryPHL: Filling In the Gaps from the Revolutionary Era

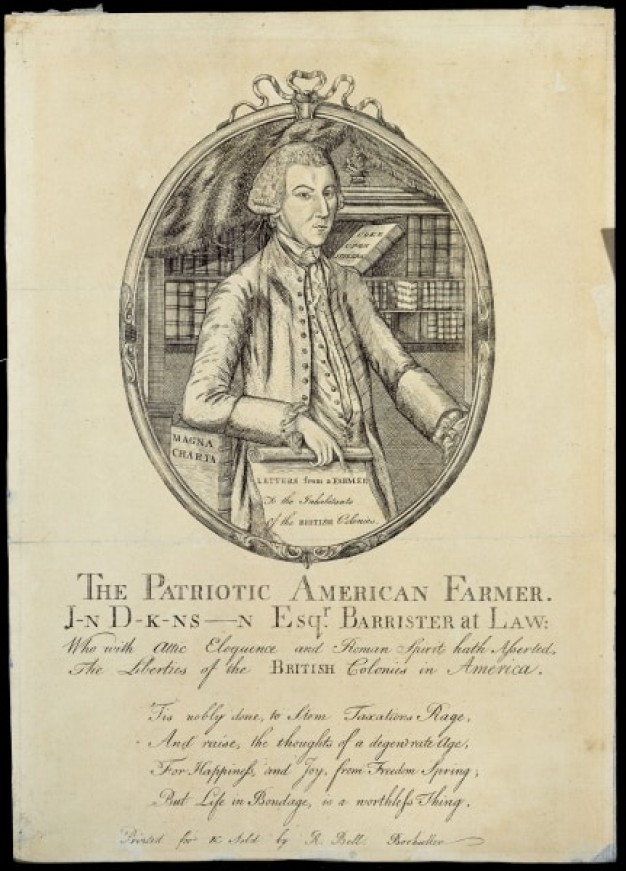

Header Image: John Dickinson. James Smither, "The Patriotic American Farmer" (1768). Library Company of Philadelphia.

Through The Revolutionary City project, the John Dickinson papers held at the Library Company of Philadelphia are now digitally accessible via The Revolutionary City portal (therevolutionarycity.org).

John Dickinson (1732-1808) was an attorney and politician during the early national period, holding significant roles in the colonial governments of Delaware and Pennsylvania. During his career, Dickinson authored treaties, proposals, and other early governmental materials. He was a ubiquitous presence throughout the American Revolution—so much so that he is often referred to as the “penman of the Revolution.” These political texts, along with correspondence and other personal materials from throughout Dickinson’s life, can be found in the John Dickinson papers.

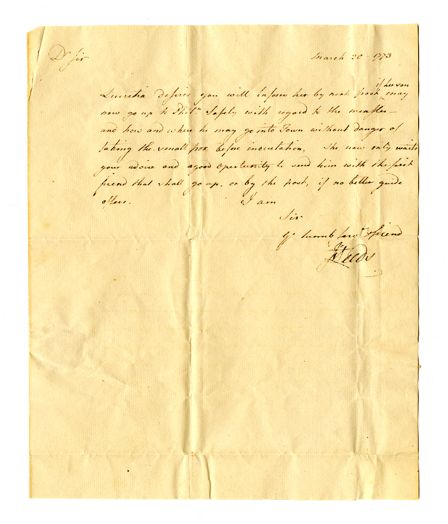

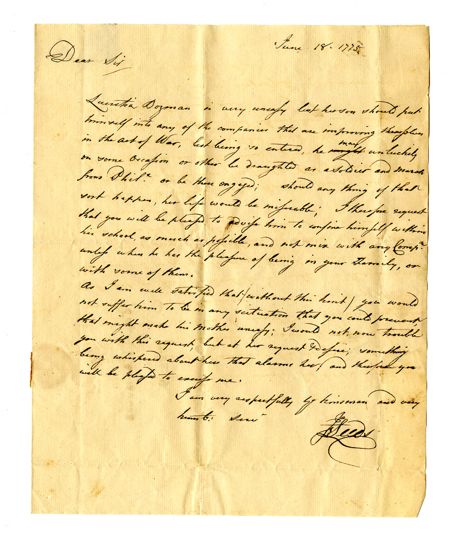

One of the first highlights I found in digitizing Dickinson’s papers was correspondence regarding Lucretia Bozman and her son, John Leeds Bozman (here and here). These documents detail Lucretia Bozman’s worry over her son’s well being as he moves to Philadelphia in 1773, while conflict between America and Great Britain continues to build. Bozman’s maternal concern is evident in these documents in her request that John Dickinson, who is hosting John Leeds Bozman in Philadelphia, keep an eye on her son and dissuade him from taking up arms. By foregrounding this perspective, researchers are able to bear witness to some of the worries that may have plagued mothers in America during the Revolutionary Era. This story is one of many hidden in the John Dickinson papers, sandwiched between letters and records pertaining to narratives from the American Revolution that are already commonly known—narratives of burgeoning tensions between American colonists and the British Crown, drafts of early government documents, and the like.

Keeping in mind The Revolutionary City’s goal of making diverse perspectives from this era more accessible, my aim as a Digitization Technician for the project was to create metadata. In the case of Lucretia Bozman’s correspondence with John Dickinson, I placed emphasis on her story through two broad metadata fields for the object: abstract and subject headings. Even though the letters are housed in folders organized broadly by date—and therefore these folders cover a wide range of topics—including Lucretia Bozman in these metadata fields is an attempt to ensure that her perspective is highlighted.

Although neither document was penned by Lucretia Bozman herself, I included her name in the subject heading and abstract sections of the folders’ metadata. Because Lucretia Bozman’s name does not exist in the Library of Congress’s Name Authority Files, her name was entered as a local heading. Additionally, a quick summary of her correspondence is highlighted in either abstract in order to help it stand out from other letters in the collection. These inclusions aim to make this aspect of Lucretia Bozman’s experience of the revolutionary era more pronounced to those who browse the John Dickinson papers on the portal.

Within other collections included in The Revolutionary City are similar examples of more diverse stories that have been digitized and for which more descriptive metadata has been applied. These efforts can be further seen as a form of reparative descriptive work, which is a pressing issue facing archives. In 2019, Yale’s Reparative Archival Description Working Group (RAD) formed in order to develop guidelines and resources for implementing reparative archival descriptive work across institutions. In practice, reparative description attempts to dismantle harmful language and ideologies in archival collections through correction and/or contextualization, and to do so in a transparent manner that is “accurate, inclusive, and community-centered.” While the focus of RAD’s work centers more so on addressing language choices in archival description, it also underscores the need to apply similar guidelines to the collections that archivists privilege. That is, reparative work can strive to uplift the experiences of voices that are lost in collections that otherwise emphasize those in positions of privilege.

This emphasis on untold and marginalized experiences of the Revolutionary Era stood out to me as one of the many exciting objectives of working on The Revolutionary City project. Undoubtedly, the history of early America is fraught, but deepening our understanding of the diverse stories from this period is one way of grappling with its complexities, and illuminates the ways in which the Revolutionary Era informs even our contemporary lives.