Promoting Useful Knowledge through Digital Bibliography

More than two years ago, postdoctoral fellows at the Library & Museum of the American Philosophical Society began what figures to be a signature product: the Members Bibliography and Biography Project, which now continues as part of a National Endowment for the Humanities: CARES grant. This public-facing digital project seeks to create a database that documents many of the most generative works and authors in the Atlantic world—including reprints and editions in any language—produced by Members elected between 1743 and 1865. This is no small task: APS Members were the who’s who of thinkers during the rise of natural philosophy and science, medical inquiry, and ethnography; most on this side of the Atlantic had deep connections to the American Revolution and the early republic. To date, the project interrogated more than 3,200 editions of more than 1,100 texts produced by 343 Members. Some 1,250 Members remain.

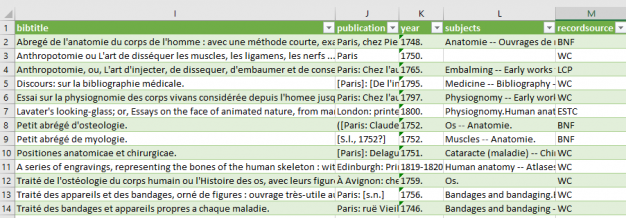

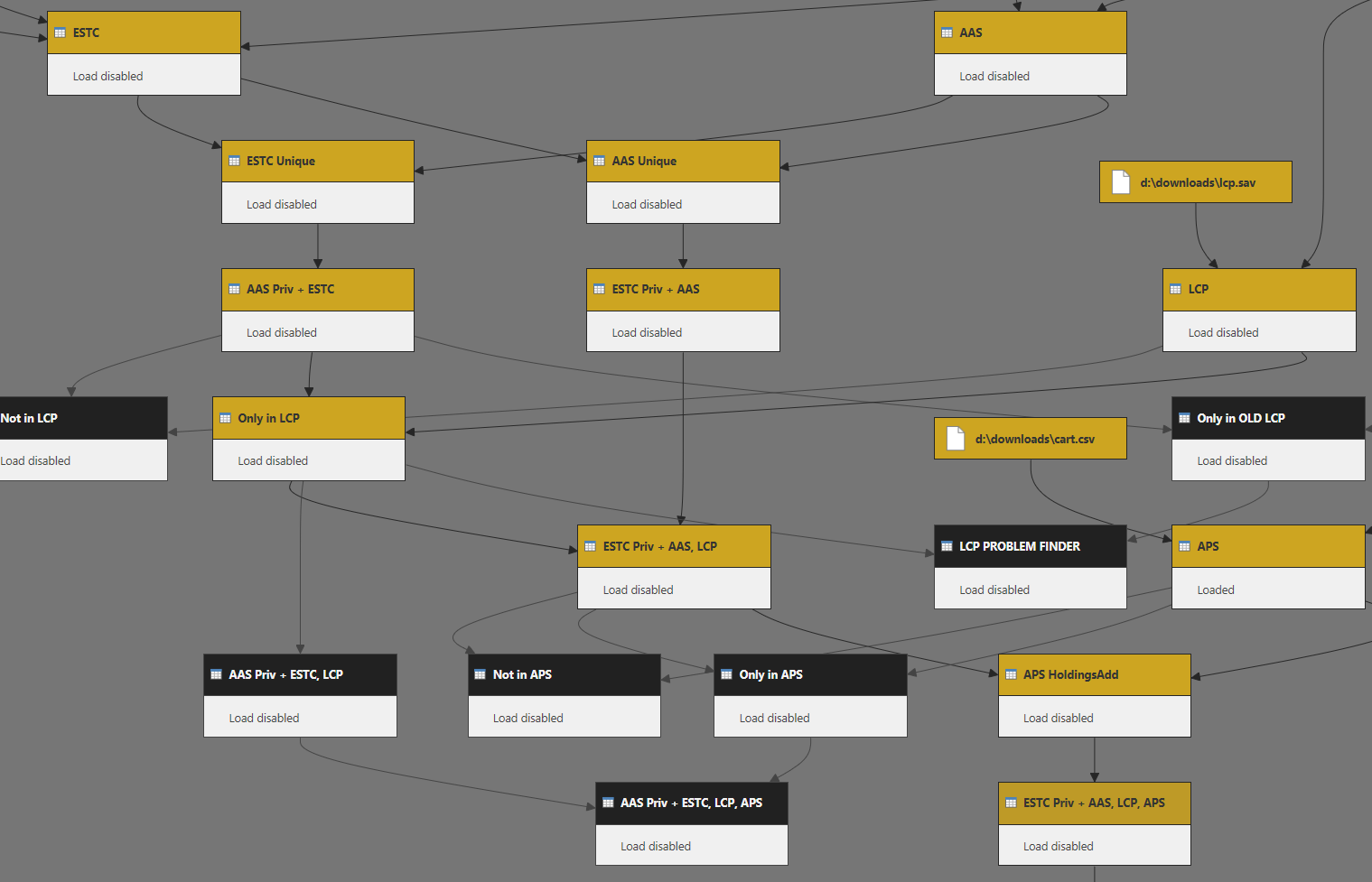

We begin by gathering information about these publications. To do this, we draw together records from the public catalog of major historical libraries to see what our Member authors published. By drawing together records from the British Library’s English Short Title Catalog, the American Antiquarian Society, and the Library Company of Philadelphia, with APS holdings—and the vast foreign-language holdings cataloged in WorldCat—we aspire to comprehensive coverage.

But getting a single book from these records into our database required some 200 mouse clicks and 50 copy-paste operations. This was not sustainable. As the early modern print revolution spun up, the profusion of editions alone would grind the project to a halt—consider Thomas Paine’s The American Crisis, later the runaway hit Common Sense—for example. No more. Although this process remains labor-intensive, the construction and continued refinement of digital automation totally transformed this project over the last nine months.

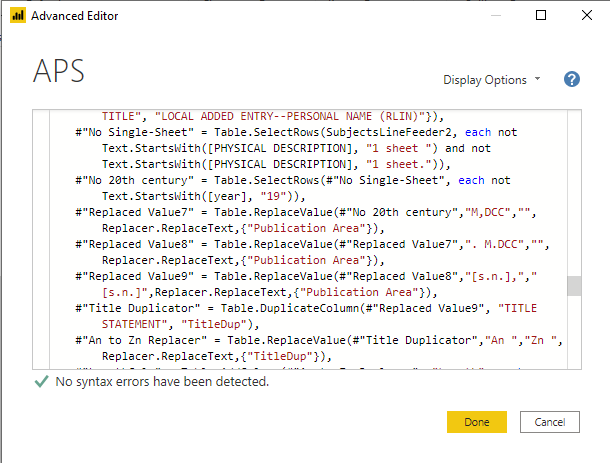

We found an unlikely solution: leveraging business software toward humanistic aims. We now fuse these records together using Microsoft Power BI, a kind of next-gen version of the venerable Excel, to generate a rough bibliography. This project seems to be among first to use Power BI for this kind of work: although built and marketed as Microsoft’s “business intelligence” solution for the corporate world, this free download is actually a kind of Swiss army knife for digital history. Scholars can use an Office-like visual interface to scrape spreadsheets, text files, webpages and even PDFs, generate any variety of charts, or produce visualizations and heatmaps with built-in ArcGIS.

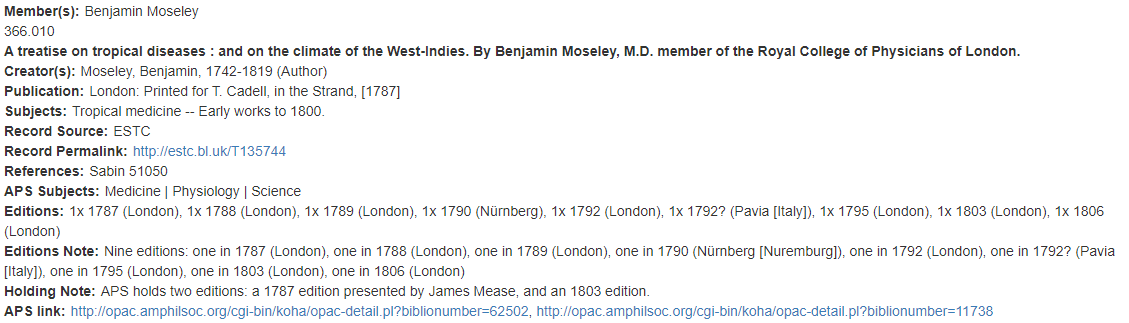

For our purposes, I wrote a series of queries to transform, format, and combine the records into our layout. Elements of style, such as punctuation—which vary from catalog to catalog—become uniform. Duplicates disappear. But for all this software-fueled automation we continue to stand on the shoulders of the bibliographers of early America: details we privilege, such as references to gold-standards like Sabin, Evans, and Shaw-Shoemaker, coalesce for easier verification.

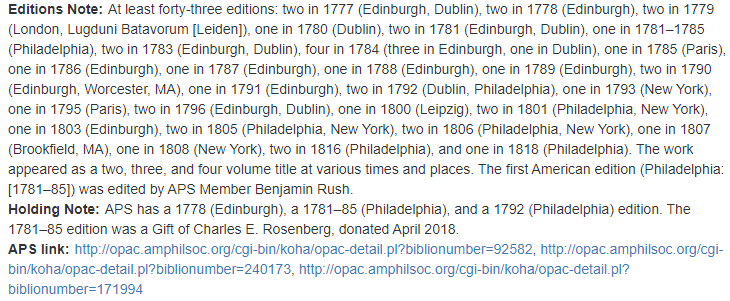

Necessity is the mother of invention, and one of our early development cases was the bibliography of Dr. William Cullen (APS 1768), the Scottish physician who trained a central corps of early Philadelphia’s medical community, including APS Members (and the founders of Philadelphia’s medical college) John Morgan, William Shippen Jr., Adam Kuhn, and Benjamin Rush. No wonder they flocked to him, for Cullen wrote the book on doctoring: First lines of the practice of physic, for the use of students in the University of Edinburgh (1777).

Not only was Cullen’s textbook wildly popular and widely reprinted. It exemplifies the roles of international exchange and constant iteration in early American science. Through Cullen and his students, a new generation of American-educated doctors and scientists elevated Philadelphia and New York ever closer to the prominence of London, Paris, and Edinburgh.

In my next post, I’ll detail further some of the promise—and potential pitfalls—of this kind of ambitious digital bibliography, by looking at one of APS’s most famous Members of the Class of 1775–85. Who will it be!?

This project has been made possible in part by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities: Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act.

Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this blog do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.