Peter Folger and Up-Biblum

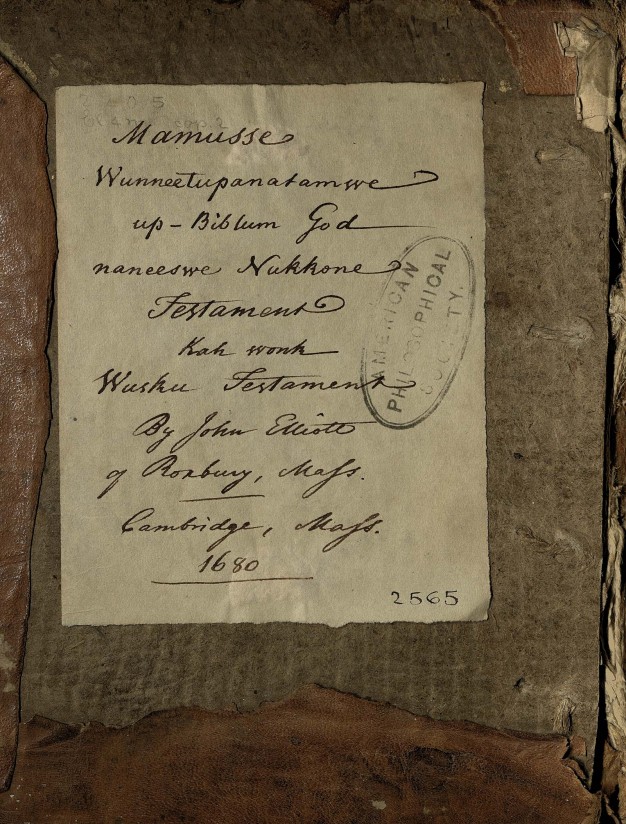

Whenever I have the opportunity, I take a moment to look through the book pictured above, even though I cannot understand a single word on a single page. Unlike me, Peter Folger could understand it, most likely all of it. You probably haven’t heard of Peter Folger, but you almost certainly know his grandson, Benjamin Franklin. The book at the APS Library that Folger could read and I cannot is Up-Biblum or, in English, The Bible. Up-Biblum (1663) was the first Bible published in North America, and it is in the Wôpanâak language, the Eastern Algonquian language of the Wampanoag homelands that extend through present-day Massachusetts. Centuries later, the leather-bound volume testifies to the emerging world of indigenous literacy in seventeenth-century New England, a world Peter Folger knew first hand.

Having left England as a young man in 1635, Peter Folger (1617-1690) spent most of his adult life living near the center of Wampanoag communities on the islands of Noepe (later called Martha’s Vineyard by the English) and Nantucket in the mid-seventeenth century. When Folger was not surveying land or trading, he was part of a small but active group of English missionaries determined to convert the local indigenous population to Christianity. While on Noepe, he and another English missionary, Thomas Mayhew, Jr., spent countless hours with their Wampanoag neighbors. After the Englishmen learned the Wôpanâak language, they held spirited debates about the inner workings of Christian and Wampanoag belief systems.

To realize their evangelist ambitions, Folger, Mayhew, and other puritan missionaries devised a four-step plan. First, they would learn local Eastern Algonquian languages. This would allow them to second, render Wôpanâak alphabetically onto the page for the first time. Third, they planned to write Wôpanâak translations of biblical passages before finally, teaching Wampanoag men and women to read the Bible for themselves. The last part was critical for Folger and other puritans because they believed that literacy was essential for all Christians: after all, they argued, how could one know God if they could not directly know His Word? English-directed efforts by Folger and men like him would have fallen flat, however, if not for the extraordinary and sustained efforts by Native men and women themselves. Ultimately, Folger saw the literacy project grow because Wampanoag men and women made it their own, first by working hard as students and then becoming instructors and ministers themselves. The Wampanoag communities where Folger lived had, arguably, the highest literacy rate of any indigenous population in North America at that time.

These literacy efforts laid the groundwork for the publication of Up-Biblum, a herculean effort in and of itself. Everything about the Bible—from translating to setting the type—involved skilled English and Native bilinguals. Much of the work that produced Up-Biblum occurred at Harvard’s Indian College. Coordinated by missionary John Eliot and made possible through the translation and printing work of Native men such as James (the) Printer and Job Nesutan, Up-Biblum was Harvard’s seventh Wôpanâak language publication and had a print run of at least a thousand. Numbers aside, the culmination of these efforts is clear: by mid-seventeenth century Wampanoag schoolmasters were teaching Wampanoag families to read the Wampanoag translated and Native produced Bible.

Twelve years after the publication of Up-Biblum, Folger and his daughter Abiah (Franklin’s mother) saw the eruption of King Philip’s War, one of the most violent episodes in early American history. For more on the experiences of Peter Folger and his Wampanoag neighbors during and after the war (and an explanation of why the APS Library holds a second but not a first edition of Up-Biblum), look for my next blog post.