Musings on Manuscripts – Metamorphic Figure of Jefferson Davis

In the spring of 1865, after four bloody years, the American Civil War appeared to finally be reaching a conclusion, and many hoped for a seamless reconciliation with the South. But after the assassination of President Lincoln on April 14, 1865, a peaceful reconciliation became more difficult. Lincoln’s successor Andrew Johnson sought to punish southern leadership. The day after becoming president, Johnson remarked: “Treason is a crime, and a crime must be punished. Treason must be made infamous." Johnson placed a $100,000 bounty on the head of Jefferson Davis. Shortly thereafter, on May 10, 1865, the Confederate leader was caught in flight in rural Georgia by two regiments of Union cavalry. In 1866, Davis was indicted for treason.

A metamorphic picture in the Vaux Family Papers (Mss.Ms.Coll.73) reflects the desire for retribution that was sweeping the North in the latter stages of the Civil War. Entitled “Life of Jefferson Davis, in Five Expressive Tableaux,” the undated print is comprised of three figures which can be cut in half and folded over to illustrate five different images, telling the story of Davis, at least in the eyes of an unforgiving, unnamed northern artist.

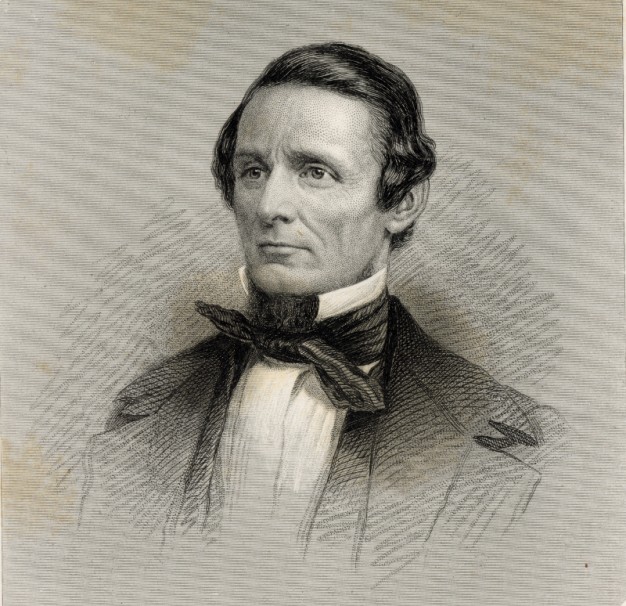

The first image shows Jefferson Davis as an accomplished patriot. He had a distinguished service record, representing his country in war and his state in politics. Davis was a decorated Mexican War veteran and a distinguished Senator for his native Mississippi. From 1853-1857, he served as Secretary of War under President Franklin Pierce. According to the artist, this first figure represents Davis “before he became a traitor.”

After the election of Abraham Lincoln, seven southern states, including Mississippi, seceded from the Union. Davis, like many men of his era, remained loyal to his state. A constitutional convention of the seceding states met in Montgomery, Alabama in February 1861, and elected Davis president to lead the new government. The next image in the sequence, in the words of the engraver, “illustrates [Davis’] treason by sitting on his own coffin.”

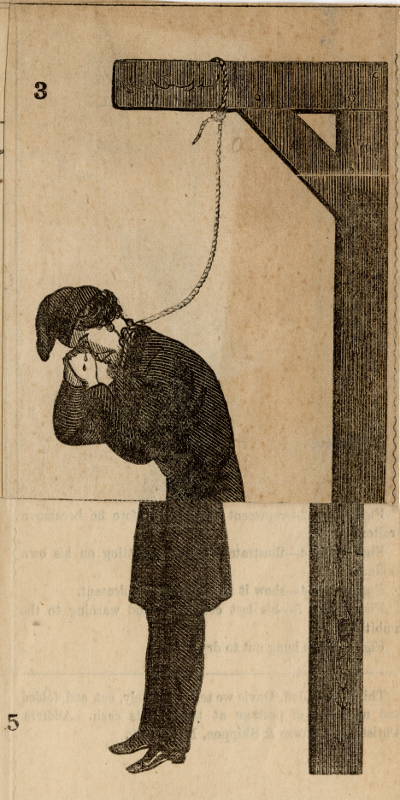

Over the next four years, the North and South fought a bloody war resulting in over 620,000 deaths. The engraver depicts Davis as an ill-fated rebel leader. His fate was sealed; his situation was “mighty unpleasant.”

The Union won the war of attrition. The next figure depicts a defeated and contrite Davis in his “last confession and warning to the ambitious.”

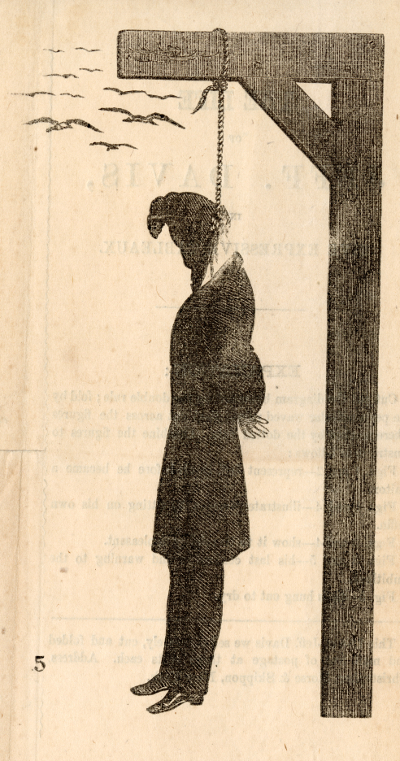

Finally, in the last illustration, the engraver shows no mercy and depicts Davis as “hung out to dry.”

Was this the true fate of Jefferson Davis? After his capture, Davis was taken to Fortress Monroe in southeastern Virginia, where he was kept in confinement in the presence of two military guards at all times. Davis’ plight, including a brief period when he was manacled in irons, was covered by the national press, making Davis a sympathetic scapegoat.

The prison doctor, John Craven, befriended Davis and published an account of his confinement in 1866. The Prison Life of Jefferson Davis did much to sway public opinion, portraying the beleaguered leader as a devout Christian with high moral character. Craven concluded, “Make [Davis] a martyr and his memory is dangerous; treat him with the generosity of liberation, and he…can be a power for good in the future of peace and restored prosperity.”

The decision of what to do about Jefferson Davis was slow in developing. Attempting to reconcile a still divided people through Reconstruction, the Johnson administration was embroiled in its own political battles. They did not wish to bring Davis to trial as such a move would mean debate over the merits of secession, a virtual refighting of the Civil War in court. In May 1867, after spending two years in captivity at Fortress Monroe, Davis was released on bail. On December 25, 1868, he was pardoned and granted amnesty, along with all other former Confederates.

In the end, Jefferson Davis escaped the hangman’s noose.

The American Philosophical Society Library is currently processing the Vaux Family Papers (Mss.Ms.Coll.73), a large and expansive collection dating from 1690-1996. The Vauxes were a prominent Philadelphia Quaker family, and the collection contains fascinating insights on the history of the early American republic, Quaker history, and family history. To learn more about the Vaux Family Papers, please see the finding aid at: https://search.amphilsoc.org/collections/view?docId=ead/Mss.Ms.Coll.73-ead.xml