Musings on Manuscripts—Lone Gunsmith in the Lone Star Republic

One of the joys of manuscript processing is discovering the unexpected. In the Vaux Family Papers, a collection of papers relating to a family of prominent Philadelphia Quakers, one of the last things one would expect to find is a cache of letters written by a gunsmith from the Republic of Texas.

In the fall of 1838, Sylvester Van Horn was an enterprising young man looking for work in the gun trade. After the Panic of 1837, jobs were hard to come by in the United States. Van Horn had trouble finding work in his native New England. He tried his hand at repairing guns in Philadelphia, without much luck.

Where could an aspiring gunsmith turn in 1838? The wild frontier…Texas.

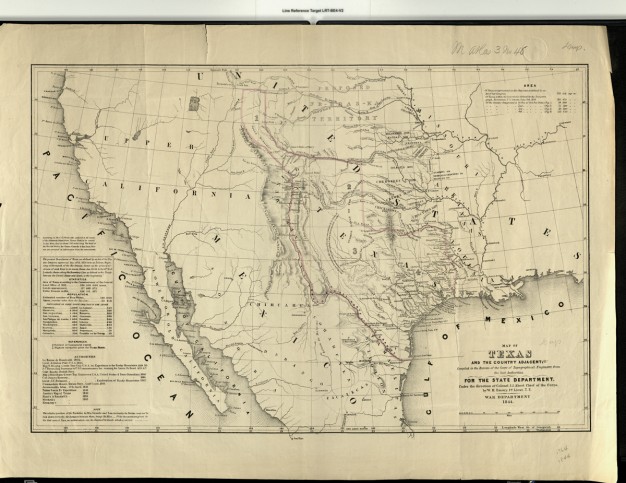

Texas in 1838 was a frontier society. A newly proclaimed republic, Texas settlers fought for and won their independence from Mexico through a short and bloody war that culminated in victory at the battle of San Jacinto in 1836. Americans began flocking to the country in earnest in search of land and opportunity.

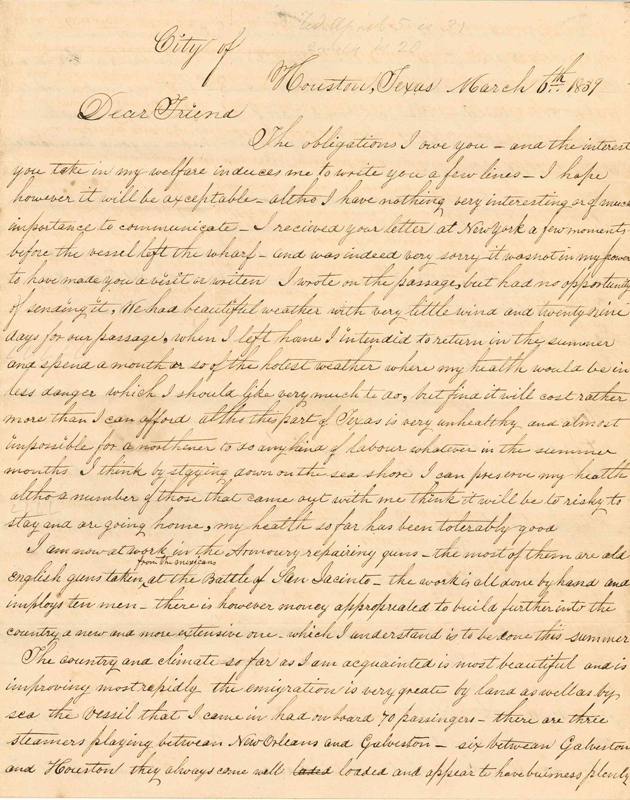

In a series of letters from November 1838 to May 1839, Sylvester Van Horn (1816-1894) described his exploits in the Lone Star Republic to William Sansom (1763-1840), the maternal grandfather of George Vaux VIII (1832-1915). Sansom was a friend of Van Horn’s step-father, Joshua Crosby (circa 1789-1856), and served as a patron to the aspiring young gunsmith. Crosby had some trepidations on the safety of his step-son in the new republic, writing to Sansom about the potential for conflict with the Mexicans and Native Americans.

Van Horn’s letters describe the precarious nature of life in the fledgling republic.

After a 30-day voyage at sea undertaken on a boat packed with German emigrants, Van Horn arrived first at Galveston, a sparsely inhabited island overrun by deer and wolves. He then made his way to the republic’s capital of Houston, “a small city [which] looks as if it grew up in one night.”

He criticized some of the people he met as “indolent and lazy,” and would “advise no one to bring their family here,” perhaps referring to the plethora of saloons and gambling houses. Despite the criticism, Van Horn was excited by the opportunity in Texas:

I like it very well. It is just the place to make money for a young man that is industrious, temperate, and steady. If he comes he must come with the determination to make something and undergo all the trials and privations of a new and unsettled country.

Van Horn also commented on the political and economic situation in the new country. Foretelling the move of the capital to Austin, he mentioned the “new seat of government…is to be located…in a more healthy and central part of the republic.” He noticed the increased trade in Texas’s ports—the importation of lumber and salt, and the exportation of cotton. And, he remarked that the republic needed to secure a loan from Europe or the United States in order to truly flourish.

In the spring of 1839, Texas’ border was far from secure. Its conflict with Mexico had never officially ended, and it struggled to come to a peaceful coexistence with Native American groups inhabiting the borderlands. Yet, Van Horn exhibited an optimistic outlook for the republic:

From the Mexicans the people anticipate no further trouble. The Indians it is true are troublesome upon the frontier, but I think the course the President is taking will soon quell them, and if the country continues to increase as fast as it has done for the past year, it will bid defiance to Mexico and keep the Indians at a distance.

Emigrants continued to pour in to Texas, but Van Horn was able to find work:

I am now at work in the Armoury repairing guns – the most of them are old English guns taken from the Mexicans at the battle of San Jacinto. The work is all done by hand and imploys [sic] ten men.

Van Horn did become disillusioned, however, bemoaning the work and pay at the armory. As an employee of the government, he was affected by the precarious nature of Texas’ finances. In the spring of 1839 his pay was delayed for some time as he had to wait for the government to print the money to pay him!

While their letters to Van Horn are not part of the collection, both step-father Crosby and patron Sansom urged Van Horn to return to the United States, until the Texas republic became more “quiet and settled.”

By the fall of 1839, Van Horn returned to his native New England in ill health and short of money. For a time, he attempted a completely different vocation, taking lessons in portraiture and miniature painting. In a letter from May 1840, his last letter in the collection, Van Horn asked his patron Sansom for a loan. Sansom acceded but died later that fall. And with that, Van Horn’s powder ran out.

Here ends the brief tale of the lone gunsmith in the Lone Star Republic.

The American Philosophical Society Library is currently processing the Vaux Family Papers (Mss.Ms.Coll.73), a large and expansive collection dating from 1690-1996. The Vauxes were a prominent Philadelphia Quaker family, and the collection contains fascinating insights on the history of the early American republic, Quaker history, and family history. To learn more about the Vaux Family Papers, please see the finding aid here.