Katharine Way, John Wheeler, and the Dawn of Nuclear Fission

Header Image: Katharine Way, undated. Photo courtesy of Physics Today.

When I was first asked whether I could contribute something original to the story of women scientists in the early decades of quantum physics, one topic immediately came to my imagination. Given that I had been mainly focusing on the eminent John A. Wheeler (1911-2008), and that part of his fame rests with his numerous students, it was natural to ask whether any women had studied or collaborated with him. As a matter of fact, once Wheeler came back to the U.S. from his stay at Bohr's court in Copenhagen in the mid-1930s, he got a job at the University of North Carolina (Chapel Hill): the very first Ph.D. he supervised there was Katharine Way (1903-1995). I had already encountered her name, but I had not done much investigation: partly because I was focused on Wheeler's activities from the 1950s on, when he reinvented his career as a nuclear physicist and became one of the leaders of the so-called “Renaissance of General Relativity” (with all its astrophysical and cosmological implications). Also, judging from a few sources easily accessible online, Way's work seemed mainly related to the compilation of nuclear data—a topic certainly important for nuclear physics, but rather remote from my research. However, in Wheeler's autobiographical Geons, Black Holes, and Quantum Foam I had also read something that I found much more intriguing: namely that, during her graduate work, Way had been on the verge of anticipating the (theoretical) discovery of nuclear fission. The topic was settled, then: since understanding the fission mechanism is also the main highlight of Wheeler's early career, I could seize the opportunity to get new insights into that, while learning more about a less investigated personality.

Very soon I had to take notice, however, that scholarship about Way's work was almost non-existent. The few relatively informative web pages were clearly redundant and interdependent; basic biographical info could be found (in the meanwhile, even Wikipedia has been updated), but there was no fresh insight into her theoretical work. There were even conflicting indications about some simple details, such as the actual year of her birth. Unlike a number of her other women contemporaries, Way managed to have a scientific career until her retirement in the early 1980s, spending the last decades at Duke University. However, there unfortunately does not seem to be an archive of her papers. In the local library, for example, there are just a couple of thin folders with a few newspaper clippings. Given this situation, Wheeler's rich collections in the APS Library clearly become a crucial, if not the primary, source.

While waiting for the opportunity to consult these collections, I made some simple observations—that surprisingly had not been done—with the already available published material. I made a comparative work, essentially, which included Wheeler's remarks about Way, or related recollections at various stages of his life, as well as Way's own published articles. Besides Wheeler’s aforesaid autobiographical book that came out at the end of the century (and thus six decades after the “facts”), the other obvious choice was Wheeler's long contribution to a 1977 symposium in Minnesota about the history of nuclear physics. Titled Nuclear Physics in Retrospect, the symposium was attended by many of the main actors (those still alive, at least). A change in emphasis between the two texts, also due to the different circumstances, is quite obvious: the one for the symposium seems a sober recollection and contextualization, while the other, more recent and semi-popular, resounds with more pathos and has some imprecise detail—quite a natural failure of human memory. However, since Way actually published a relevant paper in 1939, her research is not entirely surrounded by the mists of Wheeler's recollections, but can be, in part, independently assessed. Sure, Way’s paper was published in 1939, shortly after the actual discovery of fission. But it was based on a presentation given in New York the previous year, making the evaluation not that straightforward. However, if one reads the text in the light of the previous considerations, a reasonable working hypothesis is that Wheeler's 1977 version is the more reliable, with the other being a partial exaggeration made in retrospect.

The crux of the matter is the following: Way was investigating the behavior of rotating nuclei in certain regimes, according to a useful approximation: the liquid drop model. While looking for solutions of stability, she found none and reported this difficulty to Wheeler. In hindsight, knowing about fission (that is, a nucleus splitting into two, roughly speaking), it is quite easy to say that there was no stable solution precisely because Way was examining an unstable situation that, with a sausage-like stretching of the nucleus (Kernwurst, in German), could lead to the splitting; but, of course, while Way and Wheeler were in the process of exploring that unknown and exotic nuclear behavior, there was no obvious path ahead. The alternative, in a sense, was either to jump out of the model, assuming that its approximations were breaking down in those regimes and trying something else instead, or to stay within the model and take the breakdown as a physically meaningful indication. Wheeler and Way chose the former option; a few months later, with the actual discovery of fission, they understood that there was something deeper to it.

Abstractly speaking, this may just seem like a methodological remark or an interesting case for philosophy of science. However, knowing something about Wheeler's life, it can be guessed that the reasons for his regret at that “missed opportunity” were mainly of psychological order. During the last months of the war, a dear brother of his, Joseph (“Joe”), was killed in action between Florence and Bologna; Wheeler still got a postcard from him saying “Hurry up!”, referring to his work in the Manhattan Project, with the hope that it could bring an end to the war. That is why the few months that, in principle, could have been gained—had the discovery of nuclear fission been anticipated—so insistingly raised for Wheeler the question “What if...?”.

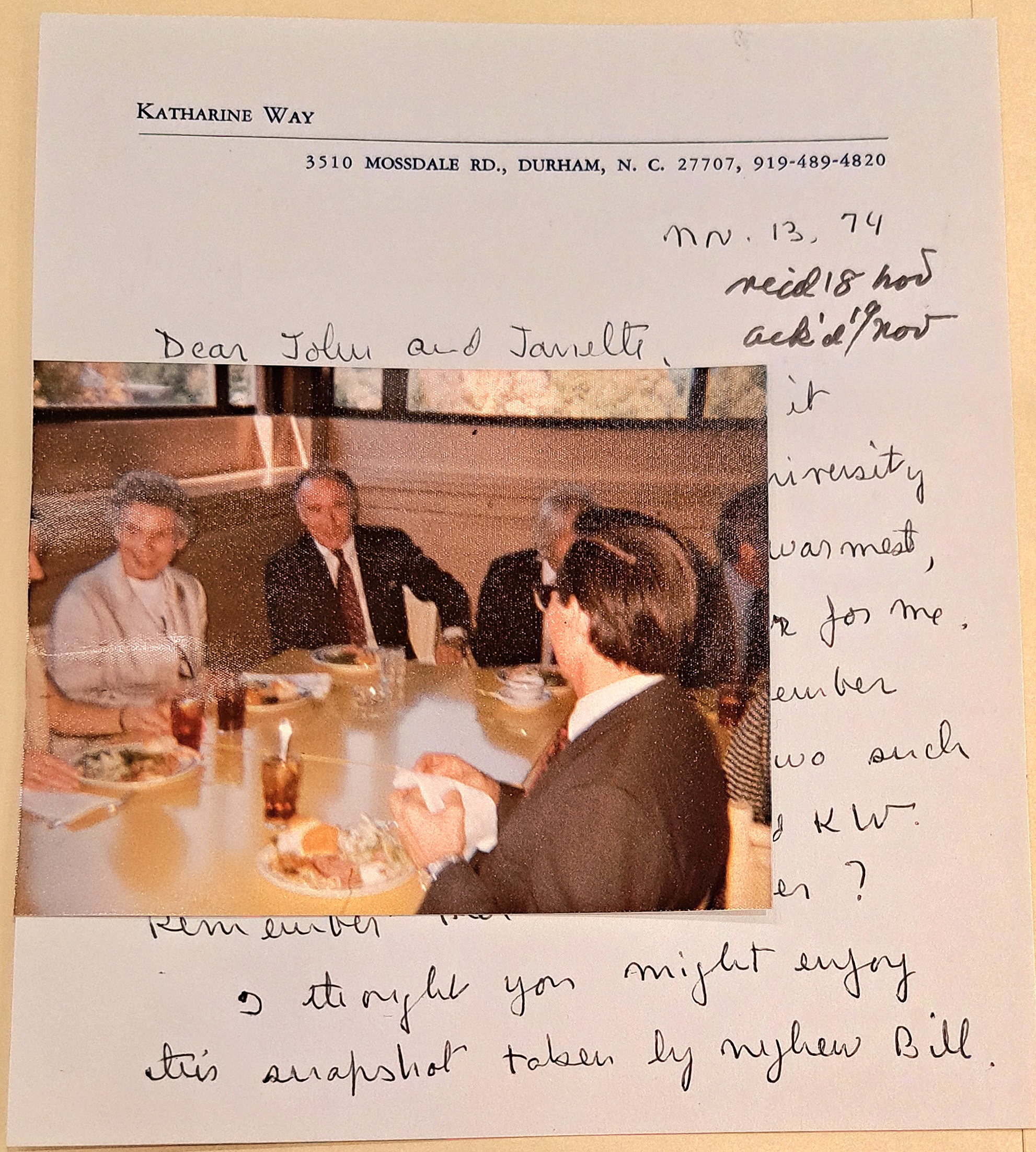

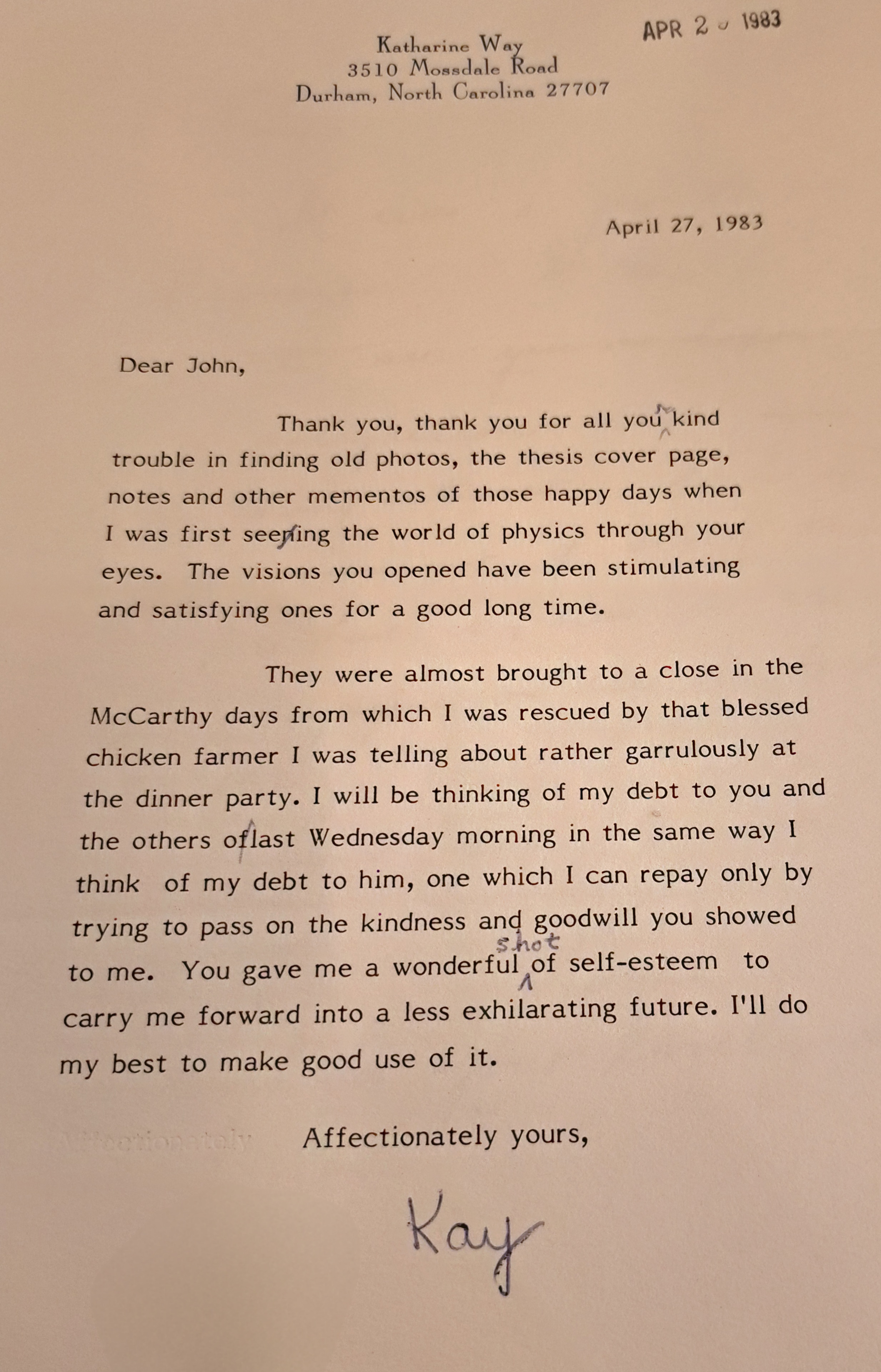

All clear, then? Not really: if one dives into Wheeler's archival collections, some further surprises can be found. First of all, some basic details of Way's biography can be established (1903 is the correct year of her birth, for instance) and we get a glimpse of the beautiful human relationship she had with her former supervisor until the end of her life. It is also possible to shed some light on her post-war activities, such as the Nuclear Data Project, and on the larger community’s perception of her work. As for Wheeler, in the light of his heuristic notes and personal annotations, it becomes clear that his meditations on the “quasi-discovery” of fission were not just a regret that he expressed with some exaggeration toward the end of his life, looking back at the dramatic century he had crossed. Even in the 1950s and 1960s, when he was struggling with an issue that would become one of the main reasons for his fame, black holes (still ante litteram), he often drew surprising analogies with nuclear fission, as if he intended to go back to the “lesson” he had learned. It acted almost as a blueprint for his scientific investigations in new realms: not much in terms of actual contents, of course, but in the spirit of taking one's theoretical tools to extremes before looking elsewhere. As Katharine Way wrote in a little poem for a celebration in honor of Wheeler, in 1977, “never think a small chance nil / for what can happen surely will.”

A paper detailing this story and discussing the various sources—published and unpublished—is currently under review. Hopefully it will stimulate further research into Katharine Way’s work and life. But this short sketch is also a little example of what a pearl fisher, to borrow an expression from Walter Benjamin, can discover in the APS Library’s rich collections.