Hearing Madame Brillon at the American Philosophical Society

Header image: Jean-Honoré Fragonard, L’Étude. Portrait of Anne-Louise Boyvin d’Hardancourt Brillon de Jouy (late 1760s). Musée du Louvre, Paris, France.

In his fanciful, poignant essay “The Ephemerae,” Benjamin Franklin used a species of tiny insects called éphémères, which live out their entire lives in a single day, as a prompt to reflect on the transience of life. Speaking in the voice of an older éphémère, Franklin concludes his vignette by referring to one of life’s few truly worthwhile pastimes: “To me, after all my eager Pursuits, no solid Pleasures now remain, but the Reflection of a long Life spent in meaning well, the sensible Conversation of a few good Lady-Ephemeres, and now and then a kind Smile, and a Tune from the ever-amiable Brillante.”

The nickname “La Brillante” refers to Franklin’s friend Anne-Louise Boyvin d’Hardancourt Brillon de Jouy (1744–1824), his neighbor in the Parisian village of Passy (pictured above). Brillon was widely known as an accomplished keyboardist and composer. She hosted soirées in her home, entertaining guests in one of the most glittering and highly regarded musical salons in Europe. She welcomed a variety of visitors—men and women, statesmen and philosophers, amateur and professional musicians. Franklin wrote that he visited Brillon “twice in every Week. She has among other Elegant accomplishments that of an Excellent Musician, and with her Daughters who sing prettily, and some friends who play, She kindly entertains me and my Grandson with little Concerts, a Dish of Tea and a Game of Chess. I call this my Opera; for I rarely go to the Opera at Paris.” Written accounts of Brillon’s salon, the surviving scores from her collection, the published music dedicated to her, and—significantly—her own compositions, present a picture of a highly skilled musician and a woman at the center of musical culture in late 18th-century Paris.

Although the manuscripts of Madame Brillon’s musical compositions were acquired by the American Philosophical Society in 1955 and catalogued by musicologist Bruce Gustafson in the 1980s, they have been largely untouched since then. As far as I know, her music has never been recorded, and that is one of the reasons I am excited to have made the recording In the Salon of Madame Brillon: Music and Friendship in Benjamin Franklin’s Paris (Acis, 2021) together with the ensemble that I direct, the Raritan Players. This recording – part of a larger research project on women and musical salons in the Enlightenment – imagines a program of music that might have been heard in the salon of Madame Brillon, juxtaposing her own compositions with works dedicated to her by professional composers in her orbit and works that she owned and played.

In the Salon of Madame Brillon features seven of her compositions that show her at her best. In particular, they demonstrate how she used the rich sounds of her English square piano – still a novelty in France at the time – to create an intimate, sentimental sound world.

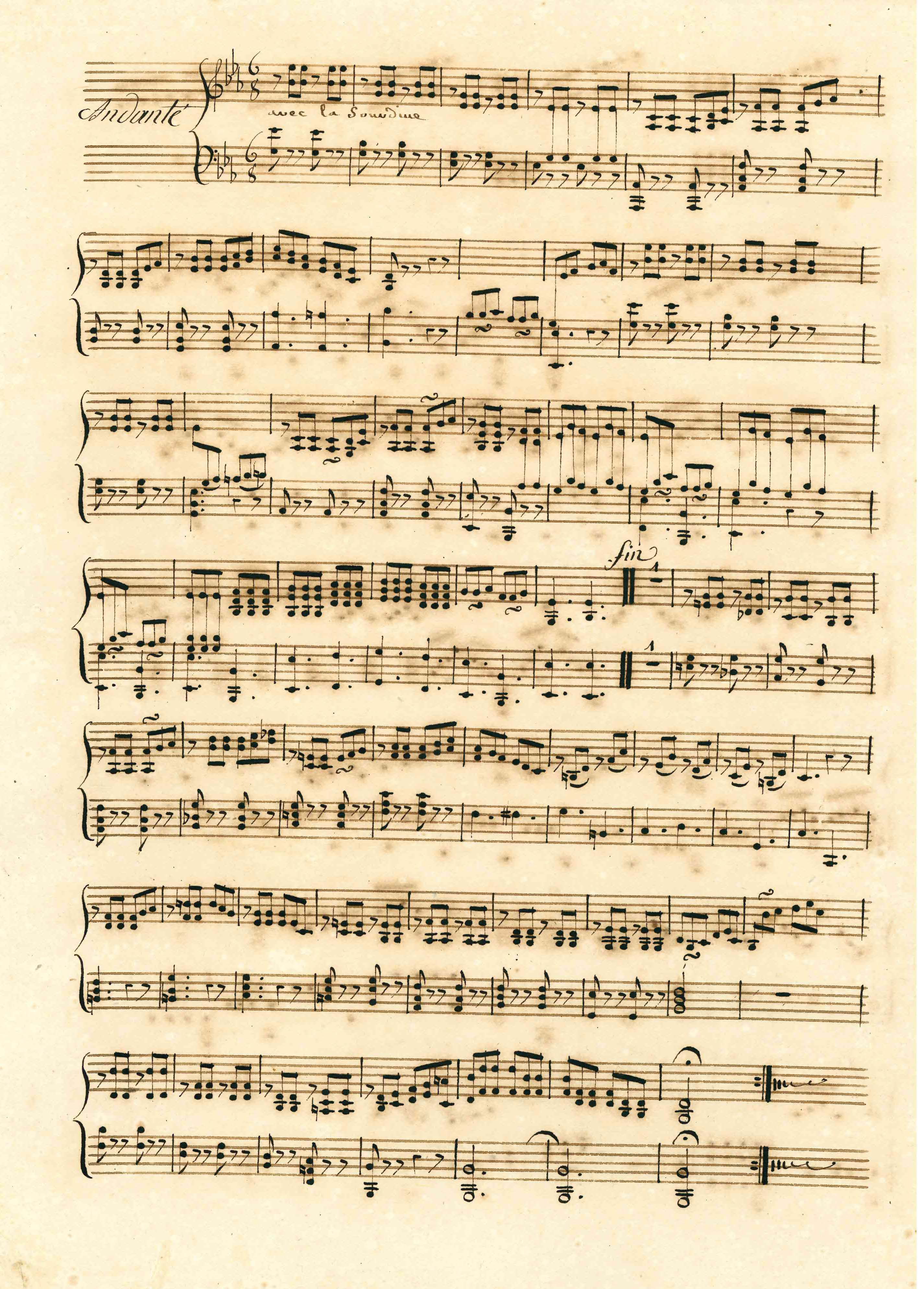

One of those is an Andante movement from one of her duets for harpsichord and English square piano, the keyboard instrument that she most enjoyed. These duets reflect Brillon’s interest in new musical technologies – and in her use of those technologies to achieve what she considered a “natural,” unstudied sound. This short movement for harpsichord and piano casts the piano in a leading role, with a sweet, simple melody. She instructs the harpsichordist to play “avec la sourdine”—with mutes—referring to the “lute” or “buff” stop, which makes the harpsichord sound more like a guitar or harp. I had the pleasure of playing harpsichord in the recording of this movement, together with my friend and colleague Yi-hen Yang playing the square piano pictured above (listen here).

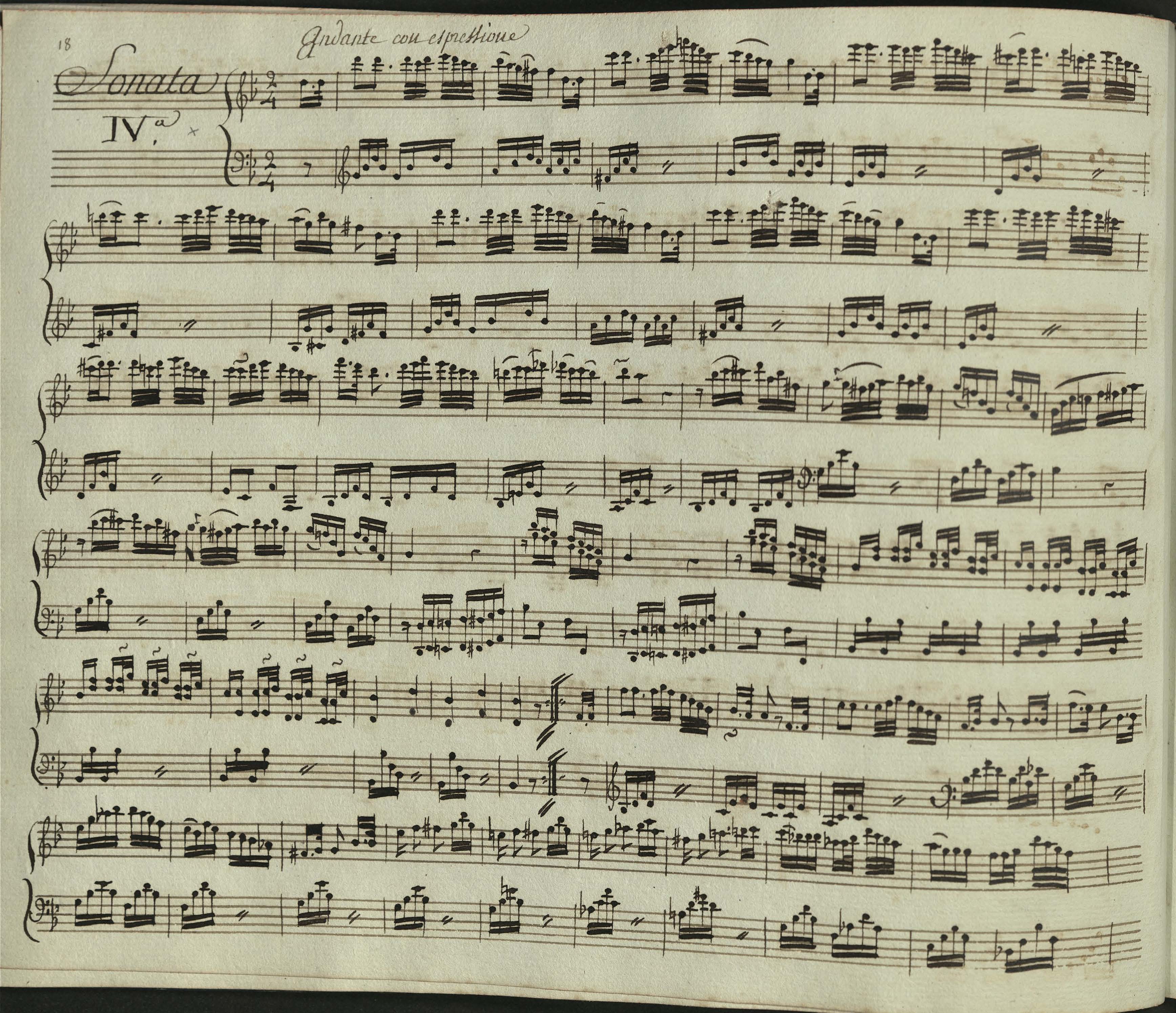

A similar type of arpeggiated, guitar- or harp-like figuration can be found in the slow movement of Brillon’s G-minor sonata. The right hand plays a lyrical, songlike melody, which floats above the gentle accompaniment of the left hand (listen here). The second movement is a tempestuous rondo that shows Brillon’s ability to navigate her keyboard adeptly (listen here).

The melodies in these keyboard pieces evoke song, and indeed, they are similar to the songs that Brillon wrote. All her songs are strophic – that is, they set several stanzas of poetry over identical music – and include a fully worked-out piano part (as opposed to a figured bass line, which was more common at the time). Many of the poems that she used for these songs were in circulation in printed anthologies of “Romances”—a genre that evokes the pastoral. The APS holds the manuscripts of Brillon's original songs, which can be found in the Digital Library here: Romances: Musique de Madame Brillon and Romances et Recueil de Canzonnettes.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau described the musical Romance in his Dictionnaire de musique (1768) as possessing “a simple, touching style and a taste that is a bit antique,” with “no ornaments, nothing mannered, and a sweet, natural melody.” In fact, this description captures Brillon’s musical tastes as a whole – she sought what was simple, touching, natural, sweet. What a joy it has been to explore these ideas in her music.

The five songs on the recording are below, together with their texts. I recorded these together with my friend and colleague, soprano Sonya Headlam.

1. [Listen here]

Dans le printemps de mes années | In the springtime of my years

Je meurs victime de l’amour, | I fall victim to love,

Semblable à ces roses d’un jour, | Just like these roses of a day,

Que le même jour voit fannies. | Which face the same day.

Ah, gardez-vous de me guérir, | Ah, don't try to heal me.

J’aime mon mal, j’en veux mourir. | I love my illness; I want to die of it.

Douce amitié, raison sagesse, | Gentle friendship, reason, wisdom,

Vous seule pour qui je vivais, | You alone for whom I lived,

Reprenez-moi tous vos bienfaits. | Take back for me all your kindnesses.

Ils ne valent pas ma tristesse. | They are not worth my sadness.

Ah, gardez-vous de me guérir, | Ah, don't try to heal me.

J’aime mon mal, j’en veux mourir. | I love my illness; I want to die of it.

N’exigez pas que le silence | Do not demand that silence

Vous dérobe mes tendres feux. | Conceal from you my tender fires.

Les derniers biens des malheureux | The last comforts of the unhappy

Sont la plainte avec l’espérance. | Are complaint and hope.

Ah gardez-vous je me guérir, | Ah, don't try to heal me.

J’aime mon mal, j’en veux mourir. | I love my illness; I want to die of it.

2. [Listen here]

Grâce à tant de tromperies, | After so many deceptions,

Grâce à tant de coquetteries, | After so much coquetry,

Nice, je respire enfin. | Artless, I breathe at last.

Mon cœur, libre de sa chaîne, | My heart, freed from its chain,

Ne déguise plus sa peine. | No longer disguises its pain.

Ce n’est plus un songe vain. | It is no longer a vain dream.

Tu crois que mon cœur t’adore, | You believe that my heart loves you,

Voyant que je parle encor | Seeing that I speak again

Des soupirs que j’ai poussé. | Of sighs that I have let out

Mais tel au port qu’il désire | But it is just as, at the harbor,

Le rocher aime à redire | The rock wants to recount

Les périls qu’il a passé. | The perils it has passed through.

3. [Listen here]

Au fond d’un bois solitaire | In the depths of a solitary wood

Le berger Tircis un jour, | The shepherd Tircis, one day,

Trouvant seule sa bergère, | Finding his shepherdess alone,

Lui parla de son amour. | Spoke to her of his love.

Vous savez, dit-il cruelle | "You know," he said, "cruel one,

Quelle est ma fidélité. | How faithful I am.

Votre rigueur éternelle | Your eternal harshness

Ne m’a jamais rebuté. | Has never discouraged me.

Si mon âme était légère, | if my soul was fickle,

Mon destin serait plus doux. | My destiny was sweeter.

Plus d’une aimable bergère | More than one amiable shepherdess

M’a voulu venger de vous | Wanted me to seek revenge against you.

Ah! qu’aisément avec d’autres | Ah, how easily I would have

J’eusse trouvé mon bonheur. | Found happiness with others,

Si d’autres yeux que les vôtres | If only other eyes than yours

Aient pu charmer mon cœur. | Could have charmed my heart."

4. [Listen here]

Un beau berger sur sa musette chantait toujours. | A handsome shepherd sang constantly with his bagpipe:

Il n’est point de douceur parfaite sans les amours. | "There is no perfect happiness without love.

De vos amants jeunes bergères n’ayez point peur. | Young shepherdesses, have no fear of your lovers.

Ils ont quoiqu’en disent vos mères: | They have that which your mothers speak of:

Ils ont un cœur. | They have a heart."

Souvent Ismene allait se rendre près du Berger, | Often, Ismene would yield to the sheperd,

Et prenait plaisir à l’entendre sans y songer. | And enjoyed hearing him without thinking of it.

Elle apprit bientôt la pauvrette, pour son malheur. | She soon learned, poor thing, to her misfortune,

Qu’on peut pour une chansonnette | That, for a little song,

Donner son cœur. | One can give one's heart.

Aujourd’hui la plaintive Ismene n’a plus d’amour | Today the plaintive Ismene has no more love,

Et tout le long de la semaine, va répétant. | And all week long she goes repeating:

Defiez vous de la voix tendre d’un séducteur. | "Beware of the tender voice of a seducer.

Hélas! Sans celle de Silvandre | Alas! Without the voice of Silvandre,

J’aurais mon cœur. | I would have my heart."

5. [Listen here]

Viens m’aider o dieu d’amour, | Come help me, oh god of love,

A poutraire celle, | To portry this one,

Celle, tant, tant belle, | This one, so, so beautiful,

Que tant aimerai toujours. | Whom I will love so much always.

Elle a bien du gai printemps | She has received from happy springtime

Gente humeur et fin sourire. | A gentle disposition and fine smile.

Blanches perles sont ses dents, | White pearls are her teeth,

Roses sa bouche respire. | Her mouth breathes roses.

The recording In the Salon of Madame Brillon: Music and Friendship in Benjamin Franklin’s Paris was produced through the generosity of the Library & Museum of the American Philosophical Society, the Robert M. Hauser Family Fund, the Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University, and the Rutgers Research Council.

References:

Bruce Gustafson, “The Music of Madame Brillon: A Unified Manuscript Collection from Benjamin Franklin’s Circle,” Notes 43, no. 3 (March 1987): 522–543

Bruce Gustafson, “Madame Brillon et son salon,” Revue de musicologie 2 (1999): 297–332.

A biography of Brillon written from the perspective of a cultural historian and not a musicologist is Christine de Pas, Madame Brillon de Jouy et son salon: une musicienne des Lumières, intime de Benjamin Franklin (s.l.: Petit page, 2014).

Claude-Anne Lopez, Mon cher papa: Franklin and the Ladies of Paris (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990).

Rebecca Cypess, Women and Musical Salons in the Enlightenment (University of Chicago Press, 2022)

Two other audio recordings on this subject, also by the Raritan Players, are In Sara Levy’s Salon (Acis, 2017) and Sisters, Face to Face: The Bach Legacy in Women’s Hands (Acis, 2019).

A documentary film exploring Benjamin Franklin's life in Paris and his relationship with Madame Brillon is Benjamin Franklin, Citizen of Two Worlds (Phoenix/BFA Films & Video, 1979), written and directed by Meredith Martindale, Toby Molenaar and produced by Stanley Cohen and Olivier Frapier.