The Early Minutes Project

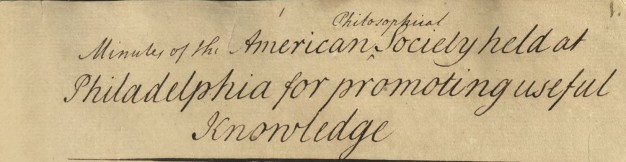

In July of 2020 with support from an NEH CARES Grant, I began the work of transcribing the early meeting minutes of the American Philosophical Society even though, ostensibly, they had been published in 1884. Clear images of each and every page of these manuscripts are also available in the APS’s digital library. These minutes of the meetings, where early Members presented papers and shaped the institution, were already widely available, weren’t they? Why the APS decided to revisit the minutes—and what we have learned so far—speaks to changing ideas about what is and what is not useful knowledge over the past two centuries. This project also highlights the benefits of providing transcriptions to accompany digital items.

If there is a digital image, why create a transcription?

If you have taken a history class, then you have probably read a transcript of a historical document. Otherwise, every high school class in the United States would have to strain to read the Declaration of Independence through plexiglass at the National Archives. Transcriptions of manuscripts, from a single handwritten copy to an edited publication, have existed for centuries. People create and publish transcriptions for a variety of reasons both personal and professional. At the most fundamental level, transcriptions exist to provide access for people who, for whatever reason, are not able to read archival manuscripts. Maybe the manuscript no longer exists, or the handwriting style is difficult to read, or the reader has visual impairments, or the archive where the copy exists is too far away to visit, or the condition of the papers precludes anyone from handling them. Even with the advent of digital libraries, the need for accompanying transcriptions remains.

If proceedings were already published, why create a new transcription?

Not all transcriptions are the same. For any project, the desired audience shapes transcriptions and any resulting published edition. The editors on one project may want to make a document more accessible for high school students and decide to standardize spelling and add punctuation for clarity. Others could be aiming to publish what is known as a diplomatic or semi-diplomatic transcription, meaning editors made a good faith effort to reproduce the page as close to original as possible, which includes but is not limited to odd spacing, phonetic spellings, and specialized letters such as the long “s.” Such details matter for some scholars and other specialists. One is not necessarily “better” or “worse” than the other, they simply have different goals.

Not all editorial decisions, however, are benign. For example, during the 19th century a number of editors began transcribing and publishing town records, accounts used by historians and scholars up through the present day and widely believed to be complete. As I and other scholars have seen firsthand, these published records, when compared with the original manuscripts, reveal unmistakable omissions. Editors removed references to entire events and even individual names, frequently with no indication or explanation for their decisions. It has been my experience that the material edited out included references the editors found distasteful or shameful. If no one had gone back and looked at the original manuscripts, no one, (as the editors intended) would be the wiser. The full extent of these omissions, and how their reintegration into the historical record could change the history we thought we knew, remains an open question.

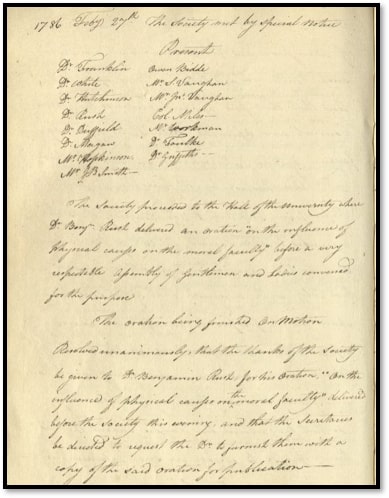

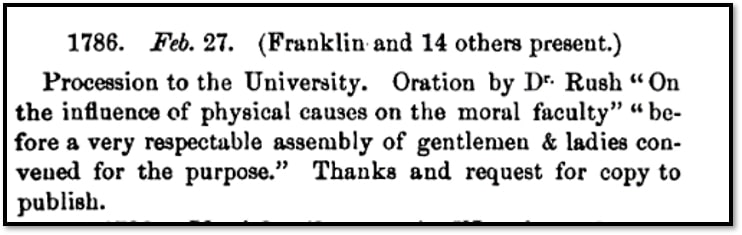

Other omissions, however, were not so nefarious, as is the case with the published early meeting minutes of the APS. Published in 1884, the editor proclaimed the purpose of this project was to both give “lively satisfaction of the Society” and preserve the intellectual content should a fire or some other calamity destroy the originals, a threat that stalks institutions today as the fire at Brazil’s Museu Nacional in 2019 made painfully clear. For preservation, the editor settled on rendering a “condensed copy” of the meeting minutes. True to this description, the publication offers capsule descriptions rather than diplomatic transcriptions. In that, they are useful in giving the key points from any meeting.

Is there anything valuable beyond the highlights?

In 1884, the editor of the minutes decided that useful knowledge was found in the highlights of the meetings but historians over the past sixty some years (and counting) have expanded that view. With the full transcriptions available, scholars, students, and anyone else can ask new sets of questions by considering the material in its entirety. Specifically, the published meeting minutes infrequently include the names of the attending members, only a count of those present. The new transcriptions will include the complete attendance list. Until the full project is complete is it impossible to determine all the new discoveries to be made from considering the cumulative materials. What is clear is that this fuller rendering of the minutes will allow more paths of inquiry.

An underappreciated additional value in this and many other transcription projects is for the people who transcribe the material. Joining this project as an essential second set of eyes to review the transcriptions has been APS’s museum guide, Angela Vassallo. New to transcribing, her experience thus far suggests the value for anyone studying early America who chooses to return to the manuscript, that there are unexpected discoveries and joy. After reviewing over two hundred manuscript pages, Angela has found that sometimes the past is more relatable than she expected. Asshe writes, “much to my surprise, the language recorded in the Minutes and the English spoken today are far more similar than I expected.” Equally, the actual process of riddling through the 18th-century handwriting brings its own unexpected rewards. “I have particularly enjoyed the magic 'spark of inspiration' that occurs,” Angela continues, “when you stare long enough at an ambiguously rendered sequence of letters, unsure what the author was attempting to write, and suddenly it comes to you. You've read the word. Sometimes this process takes multiple visits over multiple days, and yes, becomes increasingly frustrating, but the longer it takes to decode, the more satisfying that 'spark' becomes.” The project is indebted to Angela’s determination.

With the support of the NEH CARES Grant, the APS will be able to offer transcriptions to accompany the digital images of the early meeting minutes. This combination offers learning opportunities for scholars, educators, students, and anyone else interested in the Society’s early history. New discoveries will depend on the questions people ask and not on access to the material.

The APS meeting minutes transcription project, part of Benjamin Franklin’s American Enlightenment: Documenting Early American Science at the American Philosophical Society, has benefited from the time, expertise, and knowledge of many including: Angela Vassallo, Cynthia Heider, Bayard Miller, Bethany Farrell, Jeffery Appelhans, Michael Madeja, Ali Rospond, Marvin Walters, and David Gary.

This project has been made possible in part by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities: Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act.

Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this blog do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.