Ben Franklin Unbound: A Lesson on Sewing

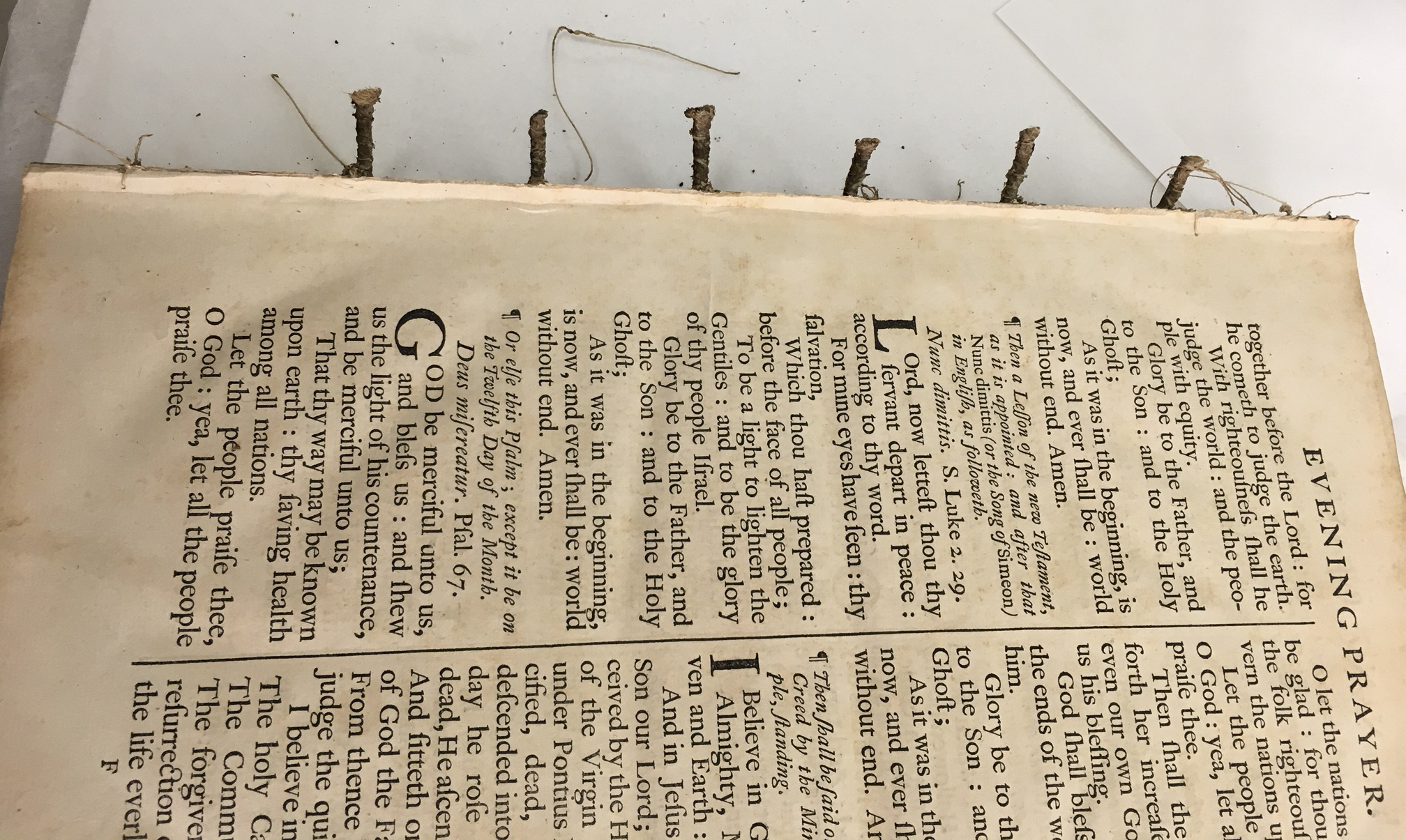

Readers are often surprised to learn that the horizontal bumps on an old book’s spine have a purpose. Those bumps, known as raised bands, are where the binding leather covers the cords over which the book’s leaves were sewn. In the image above, loops of sewing thread are visible through the damaged leather on the spine of Ben Franklin's 1760 Book of Common Prayer.

From the manuscript era through the 18th century, bookbinders created books by folding sheets of blank or printed paper into sections. After putting the sections in order, they sewed them through the fold over different types of sewing supports to create a book block or text block. Sewing supports of hemp or linen cord were common, but binders also used strips of parchment, leather, or tawed skin.

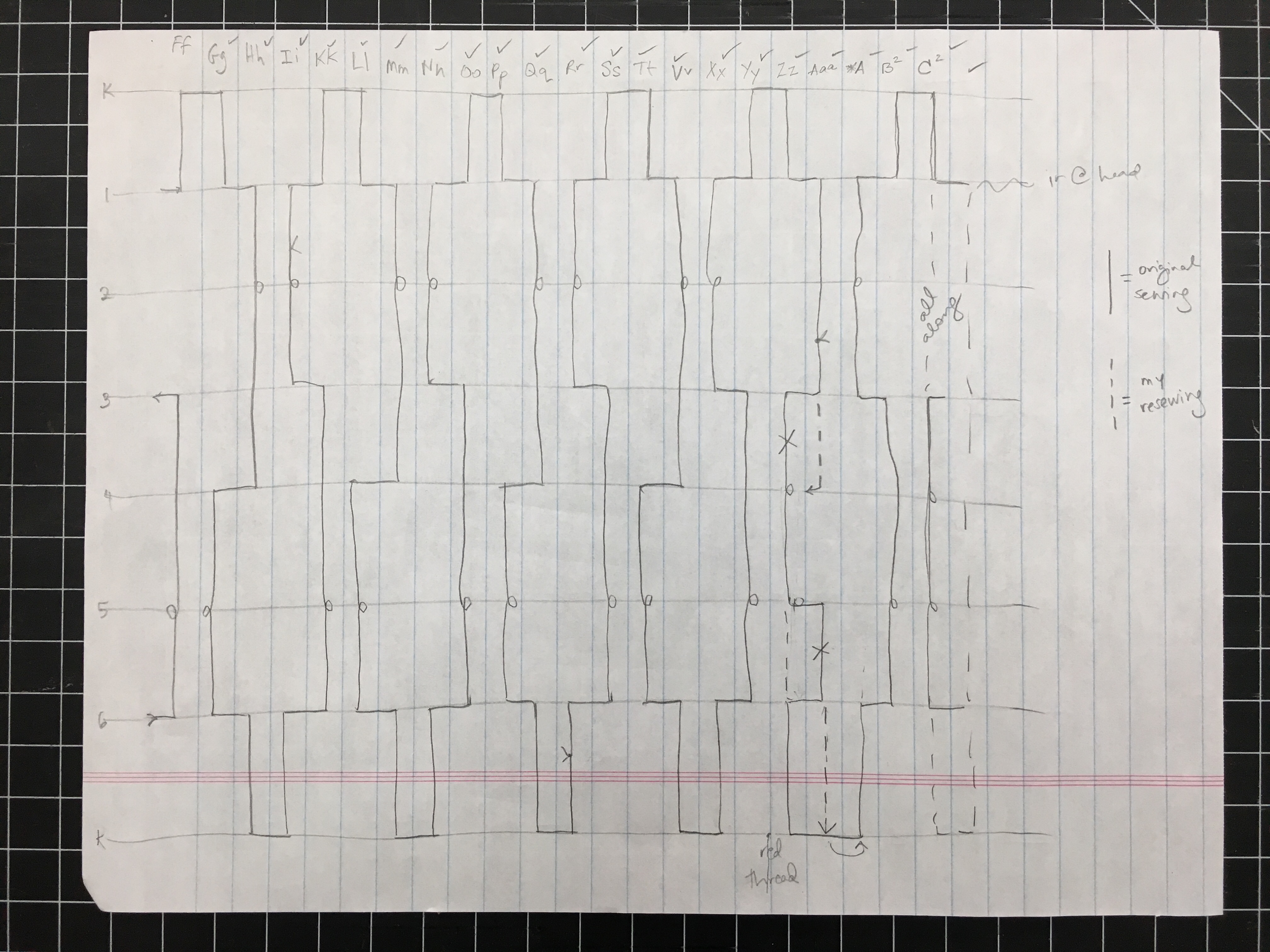

When books were written by hand and were relatively rare, binders always made them as sturdy as possible by sewing over each cord every time they came to it, a process known as all-along sewing. After Gutenberg invented the printing press and the number of books skyrocketed, binders needed ways to save time. The first sewing shortcut they invented was skip-station sewing, in which the binder skipped one or more cords as she sewed.

The second sewing shortcut was more complex, and involved sewing two sections at the same time, a process known as two-on sewing. The binder would take a stitch in one section, pass the thread over the adjacent sewing support, turn to the next section, and take a stitch in it, wrapping the next sewing support before returning to the first section for the next stitch. If the book was sewn over an odd number of sewing supports, the binder could easily pass the thread back and forth between two sections while ensuring that both of them were firmly attached to the rest of the text block.

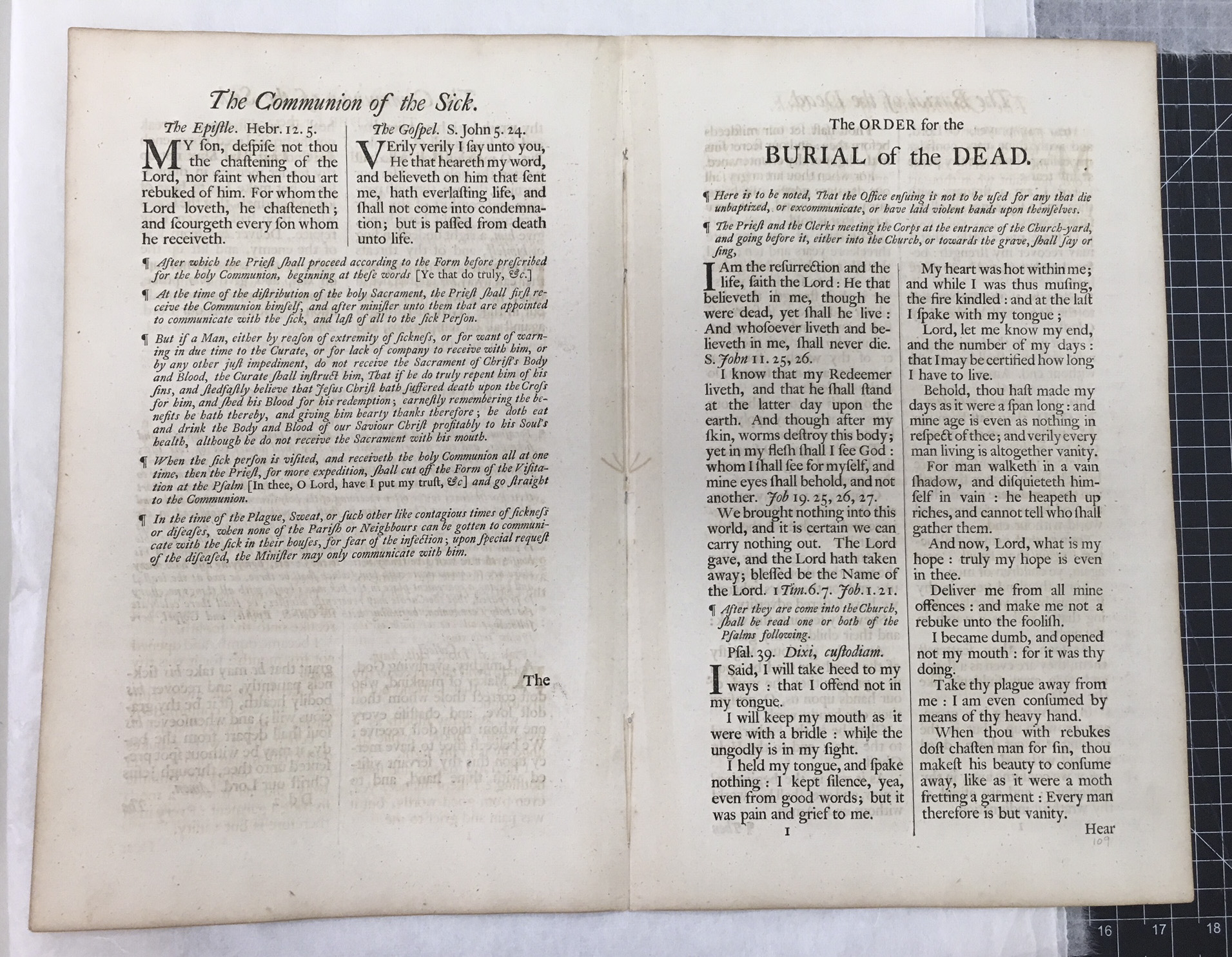

In my last post, I described the brittle, unsalvageable leather covering the spine of Ben Franklin’s Book of Common Prayer. Alas, when I removed that leather, I found that the sewing cords and the sewing thread underneath were broken in multiple places. While I had not intended to disbind the book, so much damage to the sewing structure suggested that I should. Disbinding the book would also allow me to wash the book leaves, which left an unpleasant residue on the hands of readers.

As I took the book apart, I documented every detail of its original sewing structure. Somewhat unusually, the original binder had chosen to use an even number of sewing cords—six—but also to sew two sections at a time. This required her to skip one cord in each section to get the required odd number of sewing supports. She appeared to have begun sewing at the back of the book, where the sewing pattern was somewhat irregular. By the time she had finished the first six sections, however, she had worked out her system, and it remained consistent throughout the rest of the book. One exception was signature F, which was composed of four separate leaves rather than two folded sheets, requiring the binder to whip stitch them to the rest of the book block.

Taking an original binding apart is never an easy decision, but the process often reveals hidden structural elements. In this case, I was able to observe an 18th-century binder solving sewing problems on the fly.