The ancient history of the Siouan-Catawban language family: Synthesizing archival and computational approaches

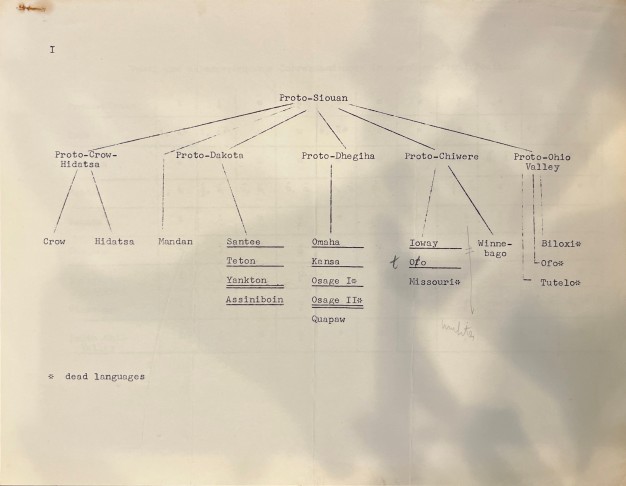

An outdated Siouan language family tree (APS Mary R. Haas Papers, Series 2, Box 23).

My dissertation investigates the linguistic history of the Siouan-Catawban language family, consisting of around 18 language varieties spoken across North America, from around the Appalachians in the east to as far as the Canadian Prairies in the west. As some of the Siouan-Catawban languages no longer have fluent speakers, accessing materials housed in archives, such as the American Philosophical Society, is essential to this work.

Linguists who study how languages change over time are often interested in determining the relationships between languages. They do this by grouping languages that belong to the same family or grouping languages belonging to the same family into their constituent subgroups. For example, English is part of the Indo-European language family, but within Indo-European, English is part of the Germanic subgroup.

Yet determining which related languages belong to which subgroup is a computationally-intensive task riddled with uncertainty. In the past two decades, computational phylogenetic methods from biology have been employed in linguistics to infer the internal structure of language families and to quantify these uncertainties.

Today, most linguistic phylogenetic studies employ lexical data, that is, data involving words—or, more accurately, cognates, words that occur in different languages believed to have been inherited from a common ancestor. The use of grammatical data—information about sounds, and word and sentence structure—has been more controversial since aspects of grammar can be shared by coincidence or by interactions between groups of speakers, among other reasons.

One aspect of my dissertation touches on this controversy by pairing phylogenetic methods with grammatical data from the Siouan-Catawban language family. Grammatical traits are selected from databases, such as the World Atlas of Language Structures, which I coded from scratch. While some information about these traits in the Siouan-Catawban languages can be found in publications, others may only occur in archival records—this is especially true for languages with no known fluent speakers, such as Catawba of North Carolina.

The APS houses Catawba materials that were recorded by Albert S. Gatschet (1832-1907), Raven I. McDavid (1911-1984), Frank Siebert (1912-1998), Frank Speck (1881-1950), Morris Swadesh (1909-1967), and Wes Taukchiray (née White; 1948-). While these materials are important for language work ranging from research to language learning, as any historian can attest, the use of archival materials for these purposes should be scrutinized. For example, words and phrases provided by Red Thunder Cloud, who masqueraded as “the last fluent speaker of Catawba,” occur in the APS materials and should be interpreted with caution. Consider also “comparative constructions” which involve constructions that express comparisons between two nouns, such as Logan is taller than Taylor, and are poorly described for Catawba (cf. Lieber 1858).

The Raven I. McDavid’s notebooks are of particular interest because, to my knowledge, they contain the only Catawba sentence, ji̜kusɛ ot hapi(ču)mire̜həri, that is translated into English as a comparative construction with two nouns, “he’s taller than you.” A little detective work, however, reveals that the meaning perhaps should be more literally translated as “that person there, he is the tallest.” This example shows that while translations can be helpful, it would be prudent not to rely too much on the translations alone.

My dissertation work thus combines philology—the examination of language in written sources—with computational approaches. And while the description of areas of Siouan-Catawban grammar that are poorly understood would help to shed light on the ancient history of the Siouan languages, I hope that they can also be beneficial in future language revitalization efforts.

Sources:

Lieber, Oscar M. Vocabulary of the Catawba language: With some remarks on its grammar, construction, and pronunciation. Collections of the South Carolina Historical Society, II, 1858.

Rankin, Robert. L. The place of Mandan in the Siouan language family. Paper presented at the 30th Annual Siouan and Caddoan Languages Conference, Chicago, IL, 2010.