Unearthing Stories: Sketching Splendor Spotlight, Part II

Many hands and many minds contributed to Mark Catesby’s The Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands and William Bartram’s Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida as discussed in my last blog post. The pattern also applied to later 18th and 19th-century naturalists from Charles Willson Peale and his family to John James Audubon.

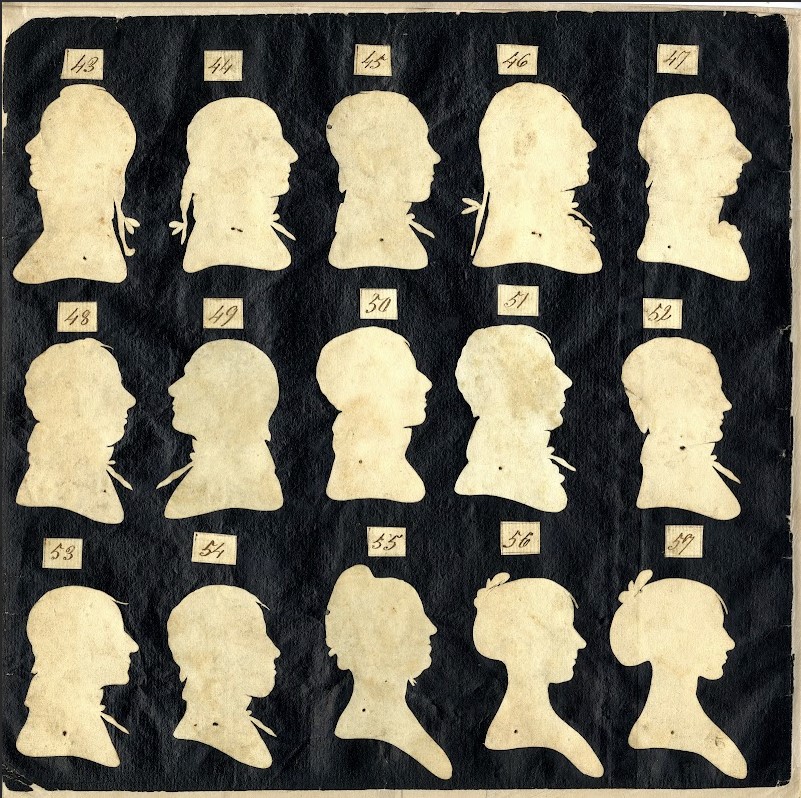

The Peale family, also featured in the 2024 APS Museum exhibition Sketching Splendor, like the Bartrams, were enslavers. Charles Willson Peale fought in the American Revolution, was a portrait artist, and also owned and operated the first successful public museum here in Philadelphia. Moses Williams worked in the Peales’ Museum with the physiognotrace and made silhouettes. Williams’s parents, Lucy and Scarborough, were enslaved by Charles Willson Peale, supposedly acquired as payment for a portrait. However, because of the 1780 Gradual Abolition Act, Lucy and Scarborough were later manumitted since they were over the age of 28 years old. However, Williams was forced to stay in the Peale household until he reached the age of 28 as well. During this time Williams was taught the physiognotrace, a device that traced the silhouette or features of a person. He charged eight cents per silhouette.

Getting your silhouette cut was a popular attraction in the early 1800s. It was affordable, quick, and it was a big pull in bringing people to the museum. It has been said that in the first year Williams made at least 8,000 silhouettes. It was so successful that Williams was manumitted a year early at the age of 27; he would go on to marry the Peale family’s white cook and buy his family a house.

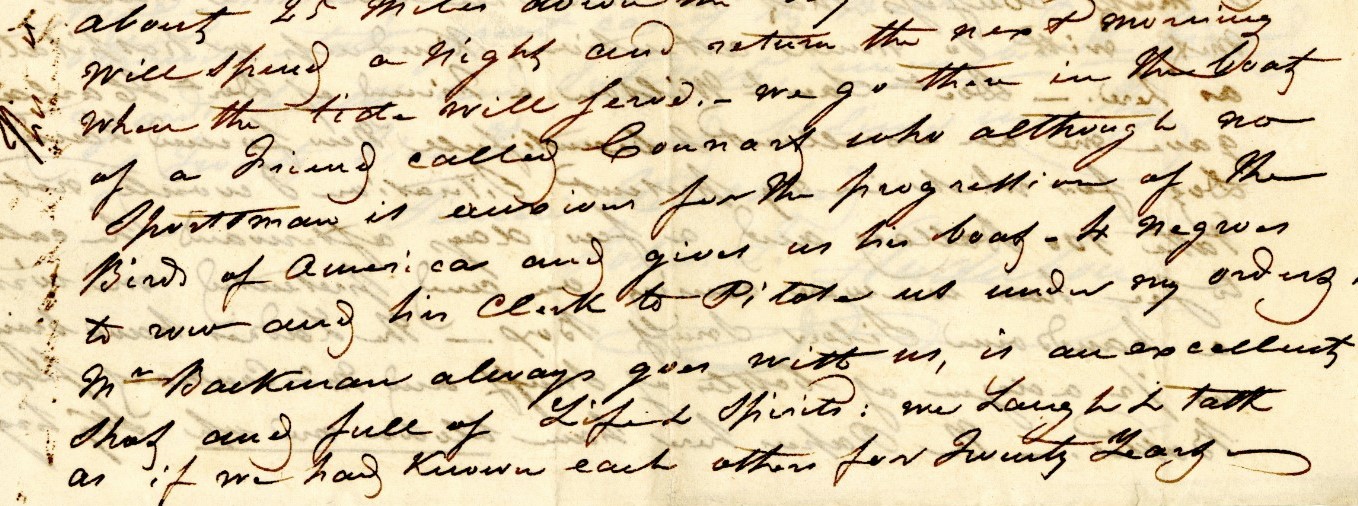

Plantation patronage aided a lot of naturalists as they traversed areas with wealthy plantation owners who were interested in natural history. John James Audubon also profited from these plantation networks and was also an enslaver. Audubon prided himself on being an outdoorsy man. He went out into the “wild”, hunted, and observed the birds he would later document. Despite his famed individualism, however, he did not in fact do all the labor of natural history himself. In a letter to his wife Lucy, on November 7, 1831, Audubon documents an expedition to an island near Charleston and briefly mentions the enslaved boatmen provided by one of his interested friends: “serve.- we go there in the boat of a friend called Connart who although no Sportsman is anxious for the progression of the Birds of America and gives us his boat– 4 Negroes to row and his Clerk to pilote us under my orders.”

Like Bartram and the Peales, Audubon relied on the labor and expertise of these enslaved people. Again, we don’t know their names, and in the published version of this account, explicit mention of these four people of African descent is erased, though this brief mention reinforces the idea that their labor was essential in helping these naturalists to get around.

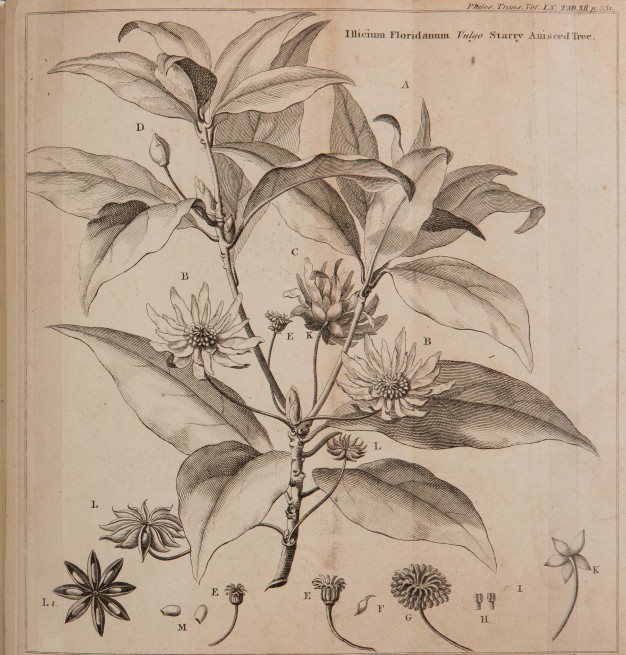

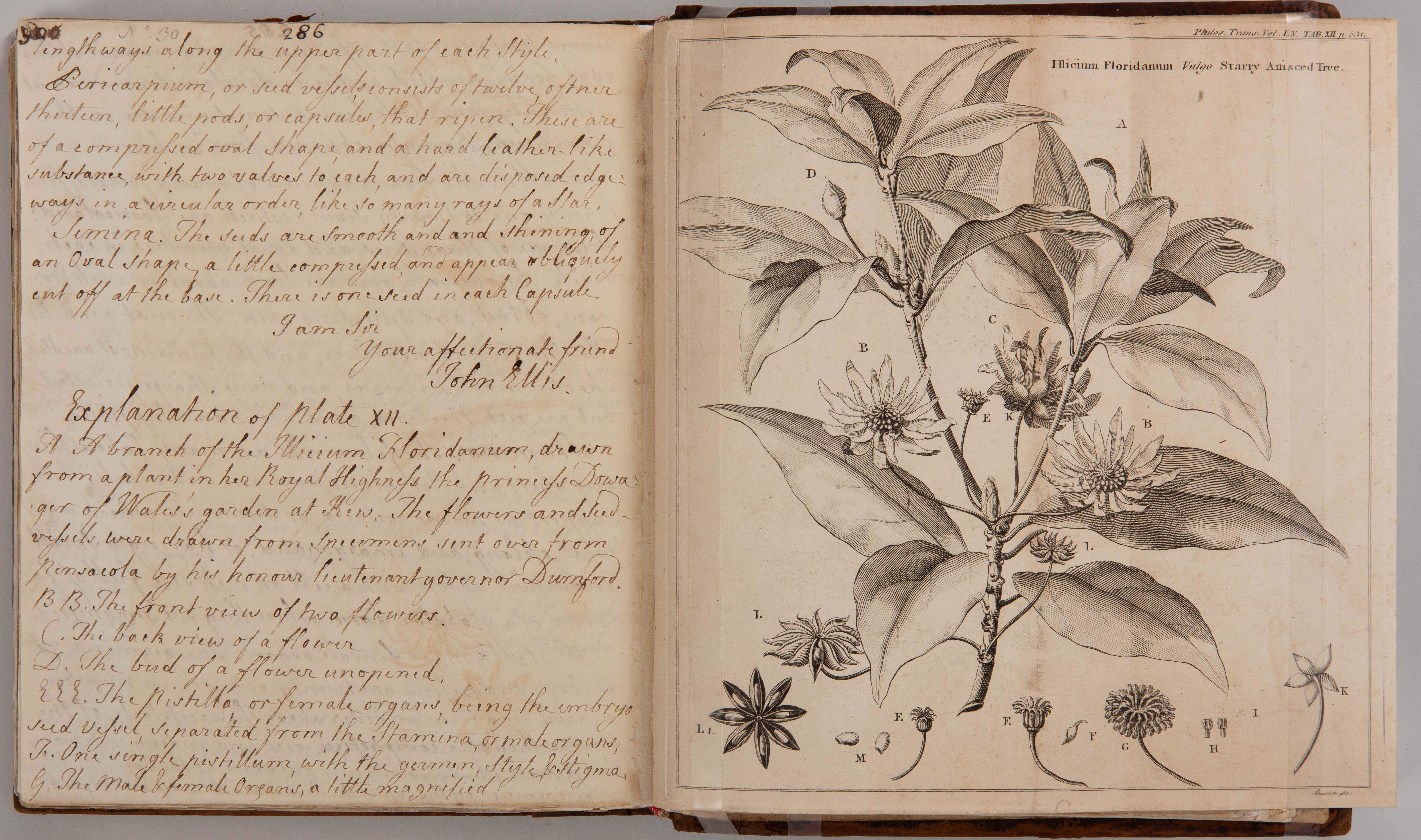

Another example of unacknowledged labor is this page from the published correspondence of British naturalist and British Agent in West Florida, John Ellis.

It shows a new specimen of star anise and details information about it. The discovery in America was credited to a man enslaved by William Clifton, the Chief Justice of Western Florida. The unnamed enslaved man was tasked by Clifton to collect “rare” plants in the wild, suggesting he had the expertise and skill to go out and identify interesting plant specimens. The enslaved man is credited with this discovery, but he is not named in the records. John Bartram would also spot and describe this specimen a few months later.

One of our last objects is Bachman’s Warbler Study for Havell PL 185 by John James Audubon and Maria Martin. Maria Martin was the sister-in-law and later wife of John Bachman, a collaborator of Audubon. Martin painted the Franklinia tree in the watercolor pictured below. She would go on to paint around 30 compositions of botanicals and insects with Audubon for Birds of America.

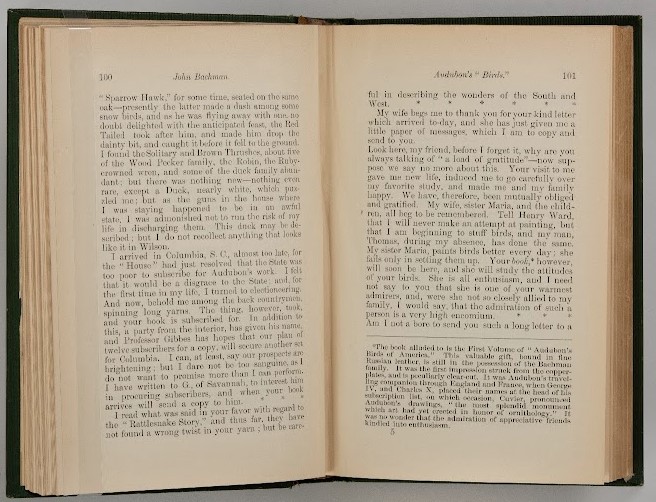

The Bachman household also included an enslaved man named Thomas. In the book pictured below, Bachman tells Audubon that Thomas had taken up taxidermy. This is interesting as well since Bachman sent taxidermy specimens to Audubon numerous times. One of them was the Bachman Warbler (named after John Bachman by Audubon).

We don’t know specifically where Thomas’s taxidermy specimens went and to whom, but it is certainly possible that Thomas could have made the taxidermy specimen that Audubon would base his watercolor after, which would later be printed in Birds of America. Ultimately, we don’t know. It is important to keep these stories and connections in mind. Science is a collaborative effort and it is important to remember that the work displayed in this exhibition was not done as a solitary pursuit. It included a lot of people from a variety of backgrounds. Some of these people have received credit, others have been left behind as a few sentences in a letter. But now, decades and centuries later, we can work to give credit to all who took part in these scientific enterprises.

The majority of these objects are on display (except for the mammoth molar) in our current exhibition, Sketching Splendor: American Natural History, 1750-1850. Learn more about visiting the Museum here.