A History of the History of Eugenics

The American Philosophical Society boasts one of the largest collections on the history of eugenics in the United States, including an expansive collection of Charles Davenport’s writings and work. Davenport was, according to one historian, at one point “America’s leading eugenicist.” The APS’s archives also hold many documents related to the American Eugenics Society and the American Eugenics Party, institutions committed to the study and promotion of eugenics in the late 19th- and 20th-century United States. During my 2023-2024 Friends of the APS Predoctoral Fellowship at the American Philosophical Society, I focused primarily on finishing my dissertation research, which focused on the ideological entanglements between the life sciences and shifting conceptions of citizenship in the post-Reconstruction United States.

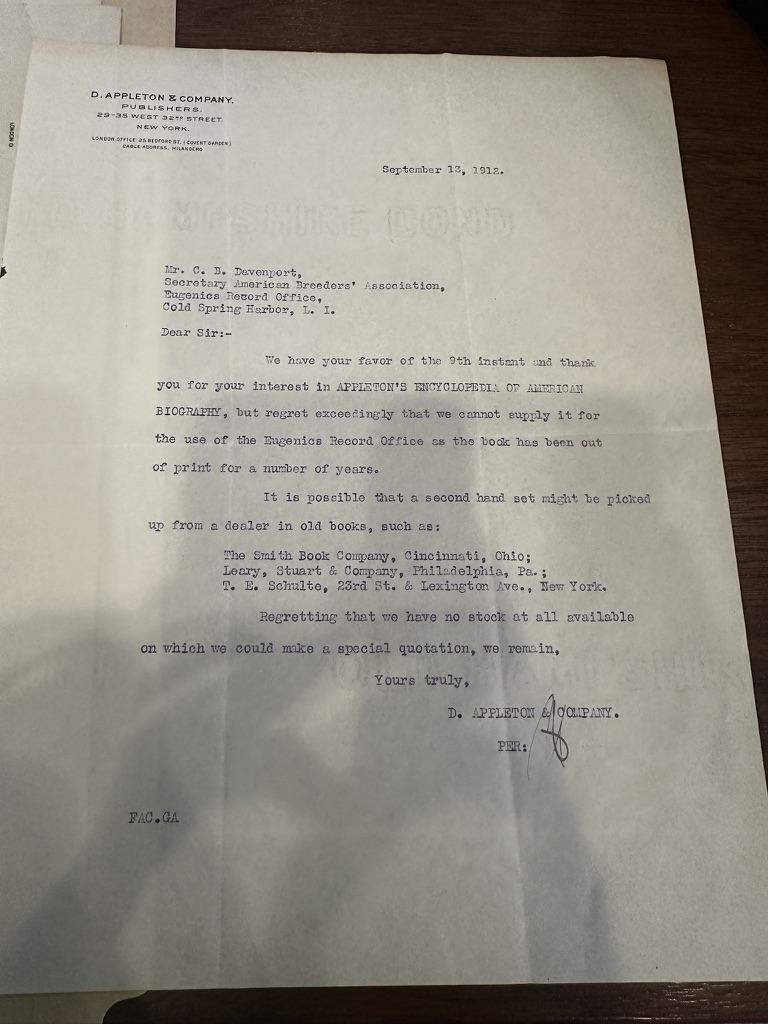

Trained in the history of the life sciences and the history of citizenship in the United States, my research led me in multiple directions: from legal cases on the juridical nature of citizenship, to patent medicines and medicine shows, to life insurance, and to evolutionary philosophy and the intellectual culture of turn-of-the-century United States. As director of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, home of the Eugenics Records Office, Davenport involved himself greatly with efforts to promote and popularize eugenics in American politics and everyday life. His records show his involvement in planning the Second and Third International Eugenics Congress, his efforts to promote eugenics to politicians, and his desire to disseminate eugenics findings to the broader national community. Through these efforts, Davenport came to be friends and close collaborators with Frederick Osborn. Osborn was well connected to the major players in U.S. eugenic science, and his efforts helped “[redirect] eugenics study in the U.S.” and contributed to “the reorganization of the American Eugenics Society”.

Osborn infrequently appears in the historiography of the history of eugenics. As both the Davenport collection and Osborn’s own collection at the APS show, this is quite an oversight. I’ve become particularly interested in Osborn’s efforts as related to the American Eugenics Society and more broadly his investment in 20th-century U.S. eugenics, both before and after the war. Considering Osborn’s connections to Davenport and their joint efforts to maintain the vitality of U.S. eugenics can help historians better tell the story of 20th-century eugenics movements—how it maintained relevance through institutional connections (like the Pioneer Fund) beyond the 1950 disavowal of Nazi race science, captured in the UNESCO Statement on Race released that year. Through my research at the American Philosophical Society, I’ve begun to explore Osborn and Davenport’s efforts with respect to eugenics through one vantage point: their embrace of the discipline of history.

Eugenicists often spoke of the future—in the possibilities of evolution and human progress, and the horrors of unchecked, ‘undesirable’ reproduction (a topic Osborn was passionate about, evidenced by his 1960 This Crowded World). The past, however, was as much a playground for eugenicists as was the future. Particularly for Osborn and Davenport, the past offered several exciting intellectual possibilities: a means of securing eugenics as a critical institution of American life, but also, as a tool through which to consider the stakes of eugenic science.

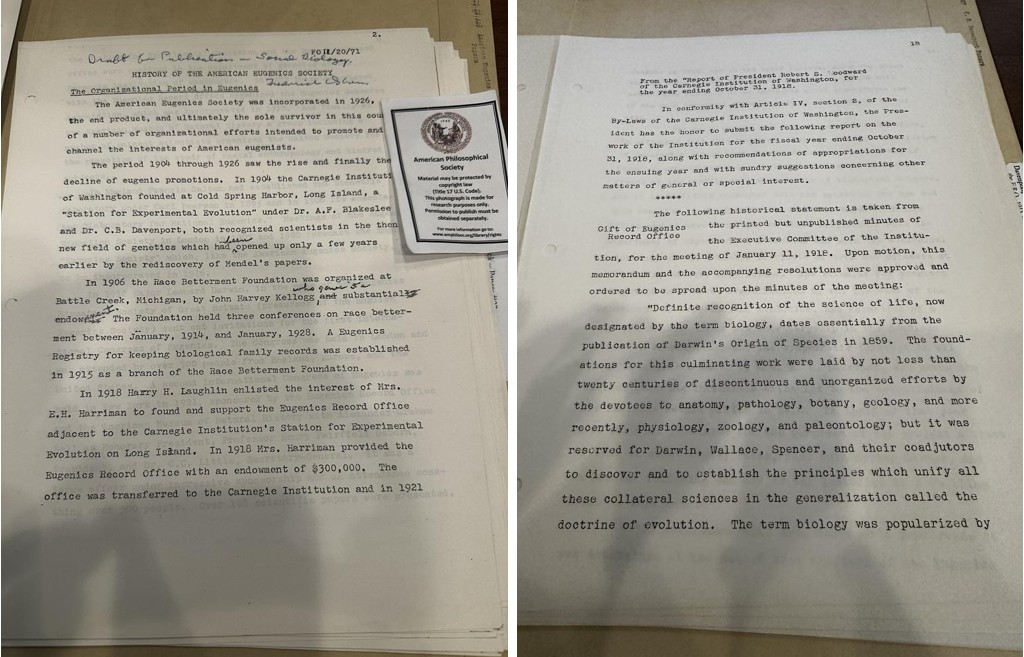

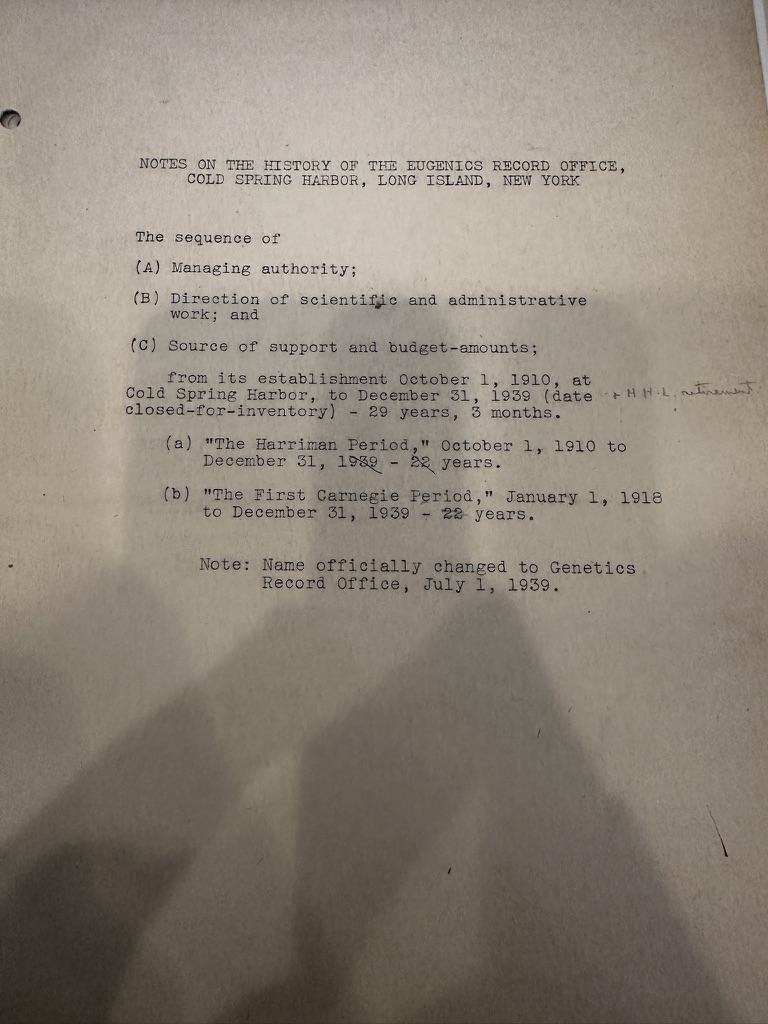

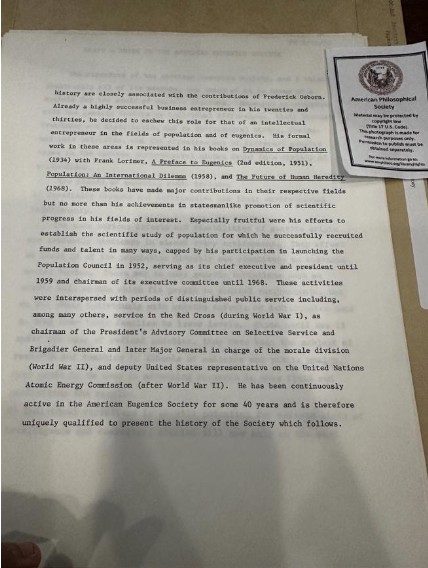

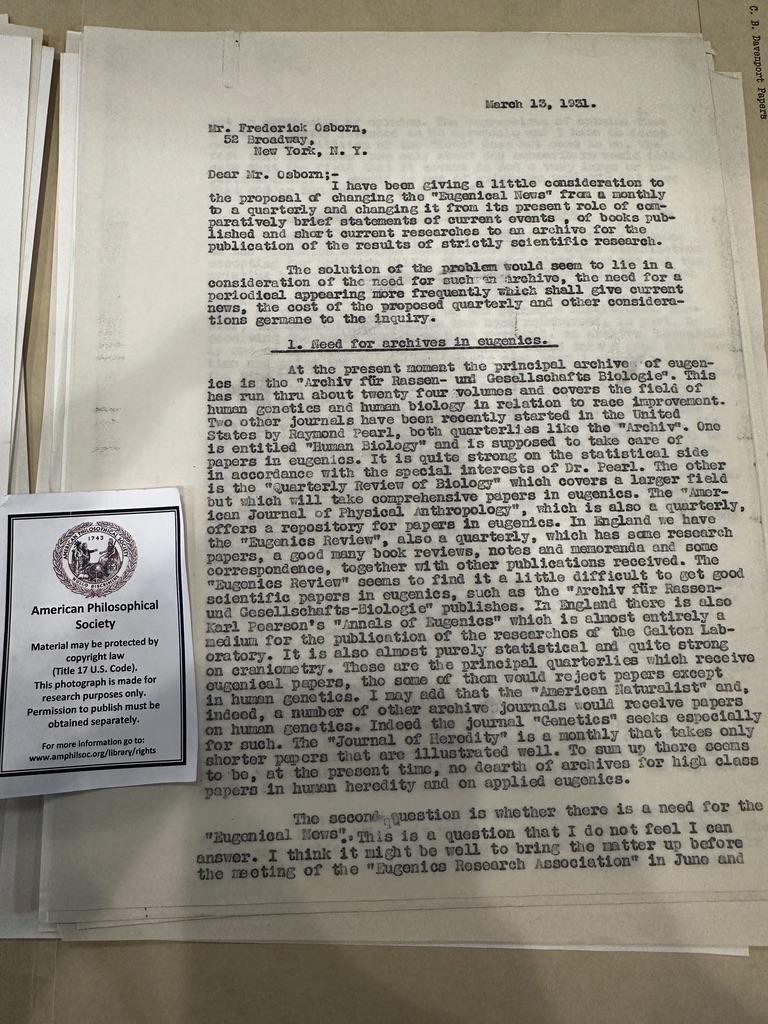

One central component of these efforts was the pair’s desire to historicize the institution of eugenics. This can be seen across several efforts to both preserve and narrate the history of eugenics. In the objects below, we can see several of these efforts. The first is an essay, found in Davenport’s letters, regarding the establishment of the Eugenics Records Office. The essay lays out what it calls the “principal objects of the office”: to “cooperate”, to “investigate”, but also to serve as a “repository” for eugenic work, what it terms “managing authority”. The second object, an essay titled “History of the American Eugenics Society”, was a major project enacted by Osborn. The essay covers the genesis of the Society, its connection with the International Eugenics Congresses, and the institutions that had supported it. In letters between Osborn and Davenport, it’s clear that they understood that building a “repository” for eugenics research would contribute to ongoing, centralized research. However, Osborn’s papers haven’t yet made clear why a history of the society was necessary. While a letter from the American Eugenics Society suggests Osborn was specifically commissioned to write a history of the organization, it’s not clear to what end such a commission was made—however, what is clear is how Osborn was considered “uniquely qualified” to tell such a history.

In the item below, it’s possible to see the clear impulse of Osborn’s and Davenport’s machinations. In a 1931 letter to Osborn, Davenport stresses the need for an American “archive of eugenics”—noting that the only other repository exists in Germany.

It will take more time and effort to understand why Davenport and Osborn desired an “archive of eugenics”. There are a few threads that seem evident from this brief overview of materials. The first is that Osborn, an institutionalist through and through, believed that the survival of eugenics would not be possible with the institutional support of, specifically, philanthropic organizations in the United States. An institutional history of eugenics, from the perspective of eugenicists like Osborn, not these organizations, may make clearer the everyday movements of these actors in their attempts to establish a solid research and archival presence for the field.

My second hunch about Osborn and Davenport’s focus on establishing an archive of eugenics is that it had much to do with their own views of the superiority of American science. Davenport’s derision regarding the German archive is in many ways a methodological slight as much as it is a nationalistic one. Historian Philip Pauly, in his monograph Biologists and the Promise of American Life, demonstrated how late 19th- and early-20th-century biologists understood the development of their field and expertise as inextricable from the broader project of consolidating American scientific superiority. Once more, an institutional accounting of 20th-century eugenics, and particularly of the work of Osborn and his relationship with Davenport, may shed further light on the entanglements between the establishment of an archive of eugenics and the distinctly “American” science of eugenics.

My meditations on Osborn and Davenport’s attachment to history, at first, seemed to view their deployment of the past as functional: did they merely use the language of history as a means to an end? Their use of history seems inextricable from the broader popularity of the scientific past in American culture at the turn of the 20th century – captured in the ongoing popularity of Darwin’s writings, and the popular work of evolutionary historian-philosophers such as Henri Bergson and John Fiske (whose fame as “America’s historian” I analyze in my ongoing book project). As François Weil highlights in Family Trees: A History of Genealogy in America, though genealogy and family trees had long been pastimes for American families, only post-Civil War is there a widespread cultural anxiety about tracing one’s heritage to a distinctly “American” pedigree (Fiske, for example, Weil writes, boasted about being able to trace his ancestry to the Mayflower).

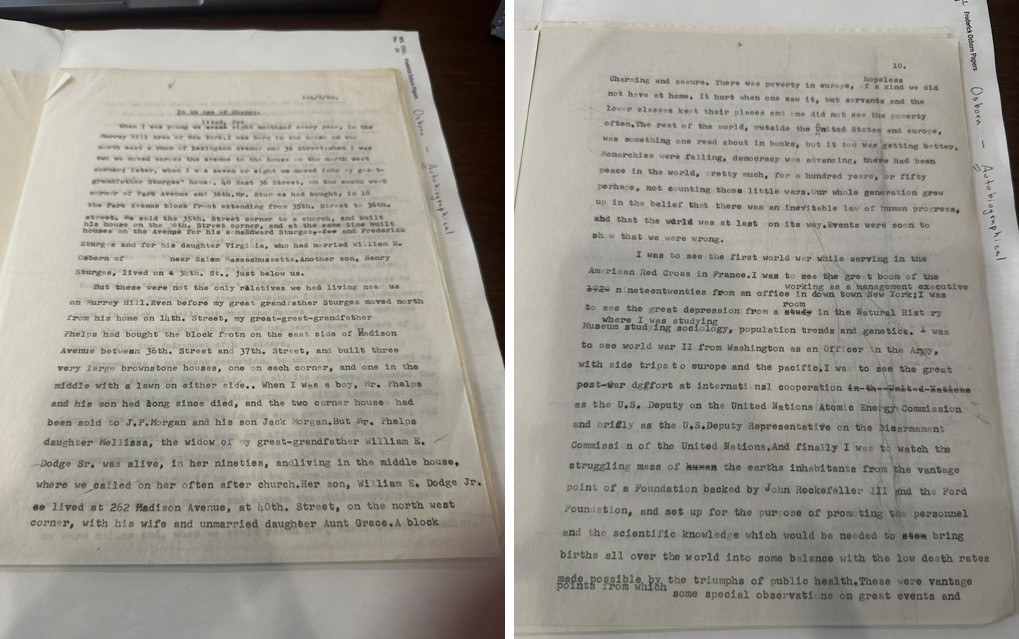

Being able to trace oneself through time required a good sense of what one might find there—an insight that Osborn, a eugenicist with an eye towards the future, seemed to pick up on. However, Osborn’s attachment to history as a method and discipline was more complex than a simple functional usage. As part of his efforts to institutionalize the historical record of eugenics, in the 1960s, Osborn sat for interviews discussing the history of his work, and even wrote an autobiography. As seen below, in a chapter titled “In An Age of Change”, Osborn’s autobiography is filled with fascinating hindsight. He writes of the demographic boom that the nation has undergone, of his “feeling for the country” in contrast to the city. However, insightfully, Osborn writes that “[his] whole generation grew up in the belief that there was an inevitable law of human progress, and that the world was at last on its way”.

Osborn’s attachments to history seemed driven as much by his attachment to eugenics as a science as by his own sense of the world—both a functional strategy for popularizing eugenics and the desire of an individual to make sense of a shifting world. History promised authority and answers—for a man committed to wresting the future from the hands of fate, his attachments to the authority of the archive remains a critically unexplored aspect of the history of eugenics in the 20th century United States. In telling this complicated dance of desire and domination, the Society’s records will prove useful.

References:

- Kelves, Daniel. “Charles Davenport and the Worship of Great Concepts”, in In the Name of Eugenics, pg. 44.

- Pauly, Philip J, and Walter de Gruyter & Co. 2000. Biologists and the Promise of American Life : From Meriwether Lewis to Alfred Kinsey. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- Weil, Francois. 2013. Family Trees : A History of Genealogy in America. 1st ed. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.