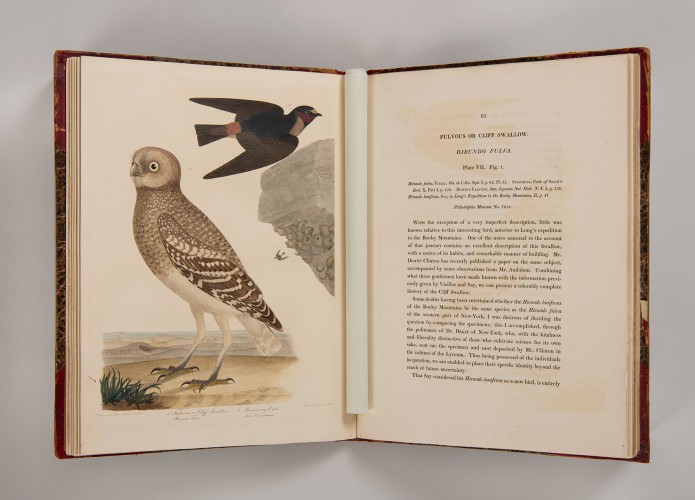

Charles Willson Peale promoted public interest in natural history through his museum, which was housed here in Philosophical Hall from 1794 to 1811. There, visitors could find a range of American animal and mineral specimens arranged in taxonomic order. Each animal was also depicted in a pleasing landscape–remember Peale was trained as a painter–that reflected their native habitat. Charles Willson Peale presented a vision of American nature as harmonious, orderly, and benevolent as the nation expanded across the continent. The museum served as his son Titian’s first classroom and he would eventually serve as its curator.

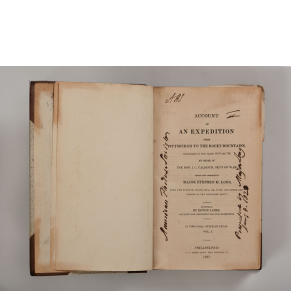

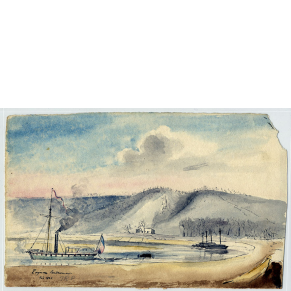

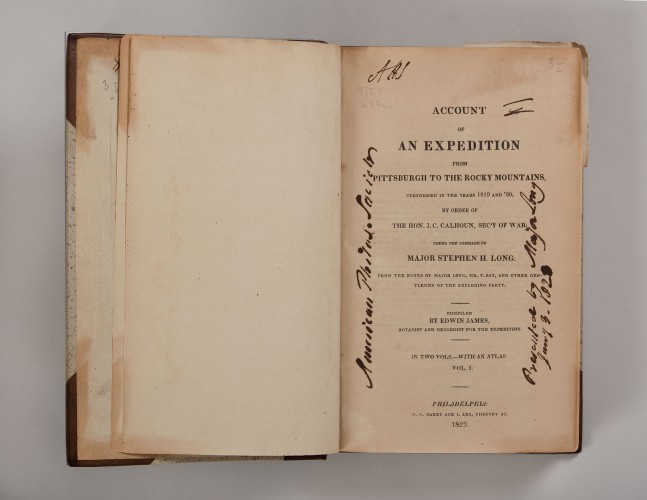

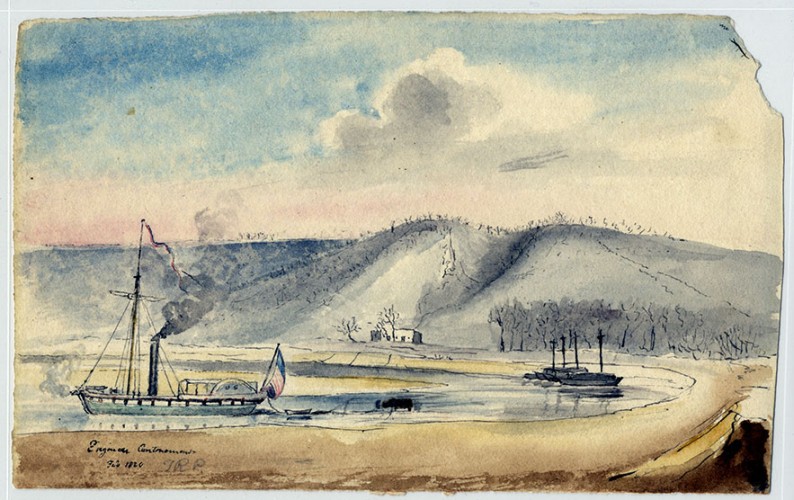

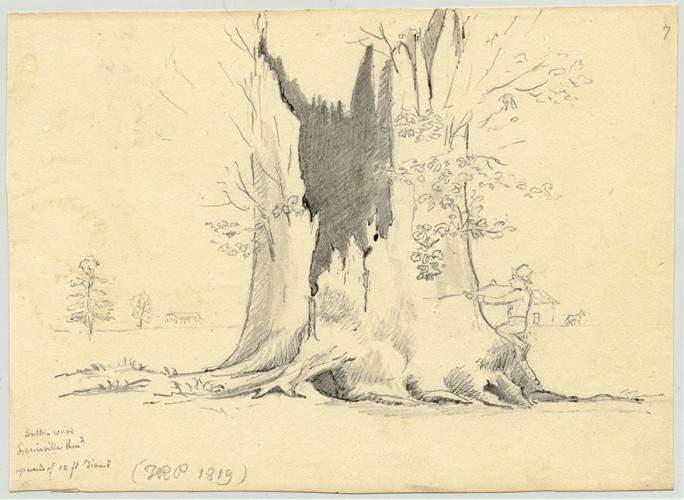

Titian Ramsay Peale (APS, 1833) belonged to a generation of naturalists whose goal was to catalog all native American flora and fauna. His father, Charles Willson Peale (APS, 1786), was a painter by training who founded one of the first American natural history museums. As a youth, Titian was also inspired by William Bartram and his commitment to fieldwork, though Titian embraced taxonomy more wholeheartedly. From 1819 to 1820, Titian went on a government-funded survey between the Mississippi River and the Rockies led by Stephen H. Long (APS, 1823). Titian’s work on the expedition focused on describing the species he encountered in these unfamiliar landscapes. He also presented the lands west of the Mississippi as ideal for white settlement in images that are both beautiful and harmonious.

The Peale Museum

Ordering Nature

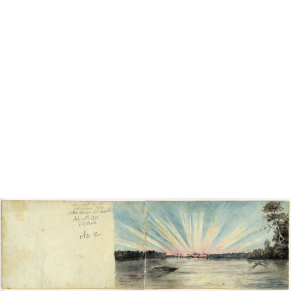

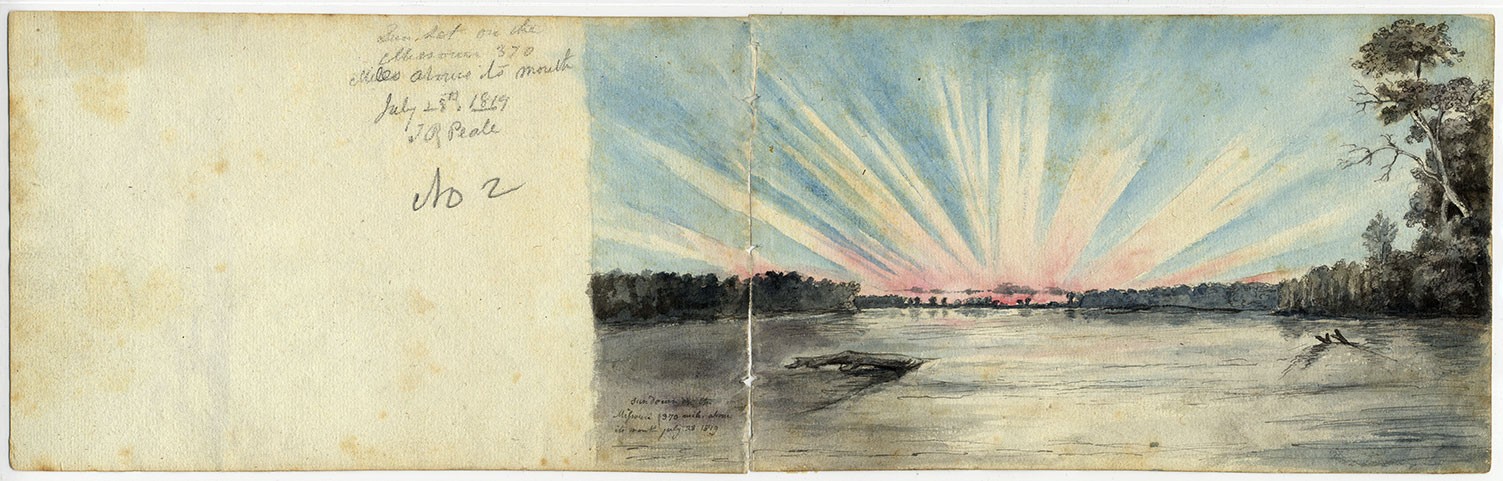

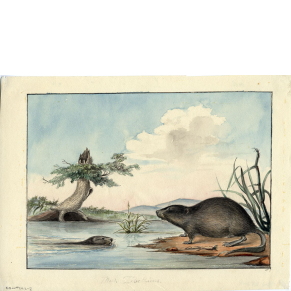

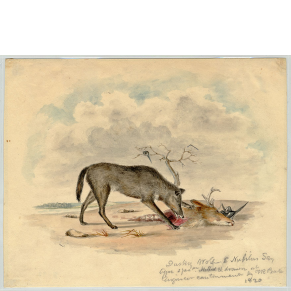

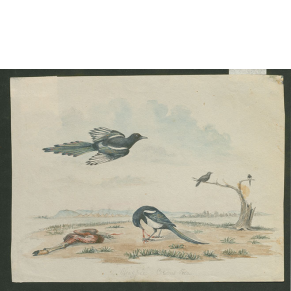

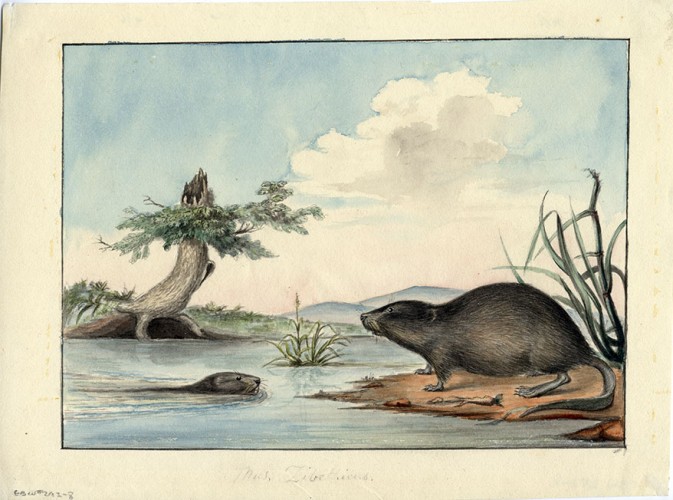

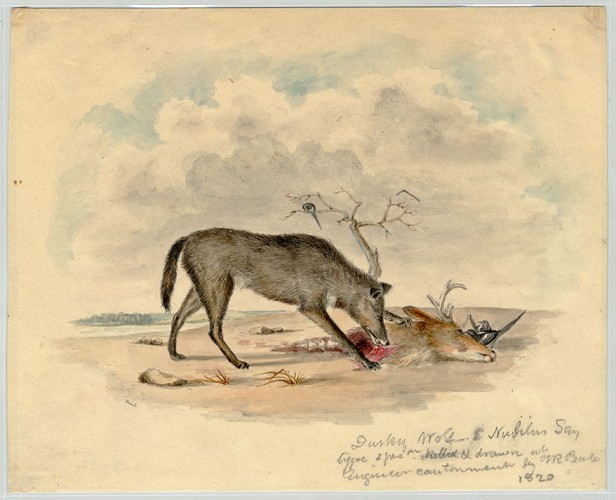

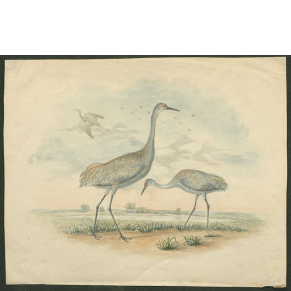

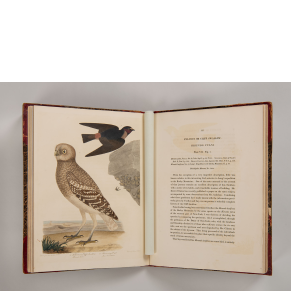

The Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804-6) was the first American expedition west of the Mississippi, but the Long Expedition (1819-20) was the first to bring trained naturalists and artists. Titian Ramsay Peale’s finished watercolors are idealized scientific illustrations of the animal’s appearance, its habitat, something of its behavior, and its diet. These images also clearly communicate the scientific information required by the government: what animals live there, the quality of the land, its plants, and the availability of water. Peale’s harmonious presentation of nature made it seem open to settlement. A few images, however, depict a harsher side of the landscape.

Titian Ramsay Peale’s finished Long Expedition watercolors, like the Blacktail Deer and Muskrats, bring together his detailed botanical and zoological studies, as well as his observations of animal behavior. In many watercolors, he presents an aesthetically pleasing portrait of the landscape, with abundant water, lush plant life, and rosy sunsets. However, the Long Expedition account presented much of the land between the Missouri River and the Rockies as harsh and unpromising for white settlement. Peale evokes this sentiment in some of his images, where storm clouds gather, or animals fight for scraps of food.

Hunting Animals, Making Science

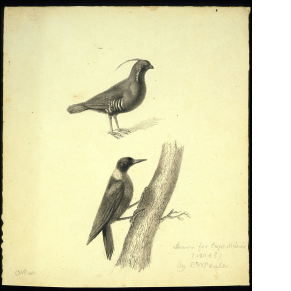

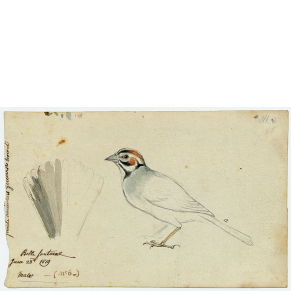

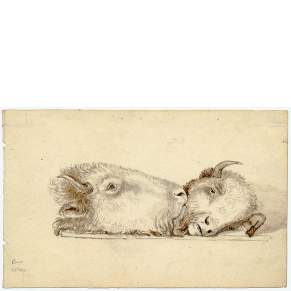

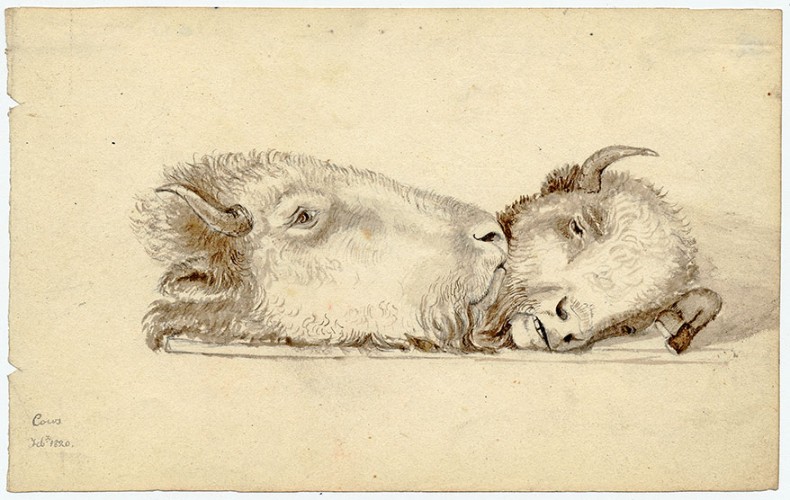

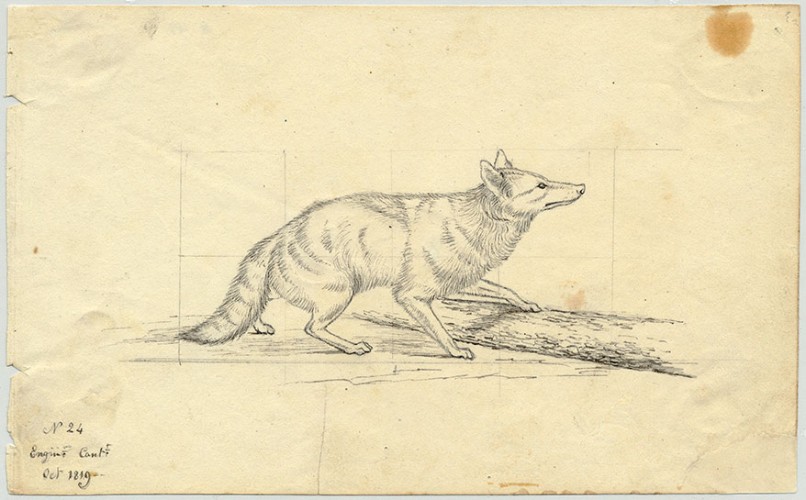

In order to study animals, naturalists often killed them. One of Titian Ramsay Peale’s main roles during the Long Expedition was hunting for both food and scientific specimens. Sometimes, a single animal served both functions. The violence behind the science usually goes unrecorded, but Peale produced a series of images that record trapped or dead animals. In these images, he seems to present his art as something that can restore life after death. The dead scarlet tanager is already restored to the brilliant color it had in life, and taxidermy will complete the resurrection. But these images also highlight the relationship between scientific knowledge and violent control.

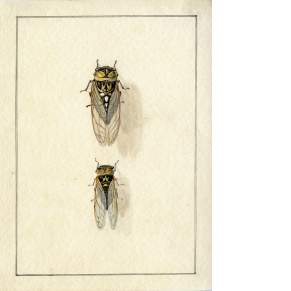

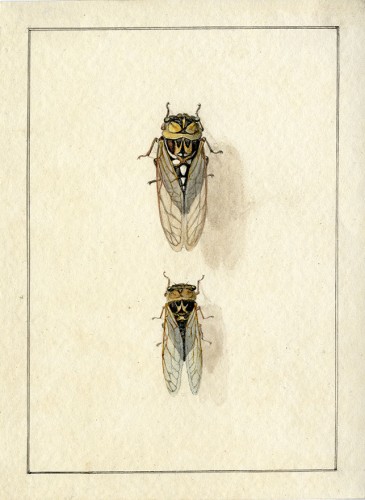

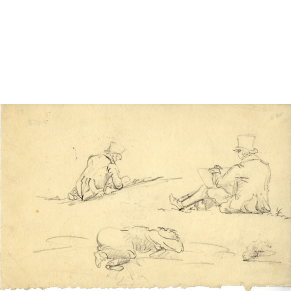

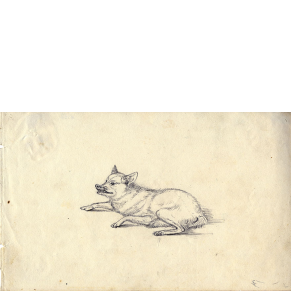

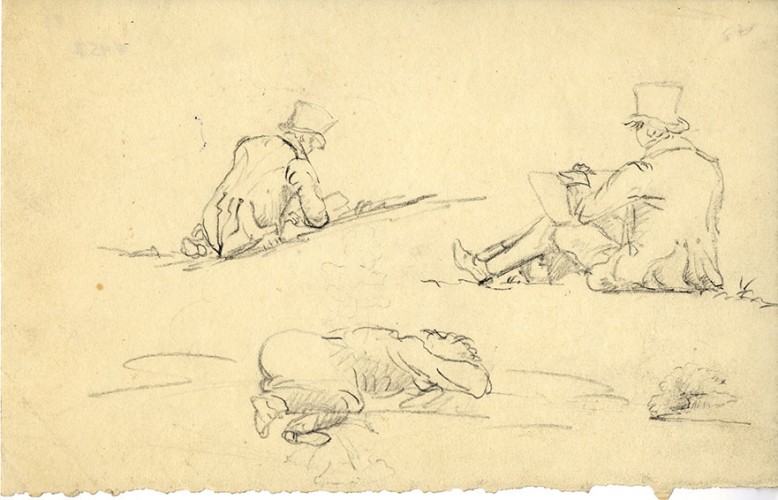

The Art of Natural History

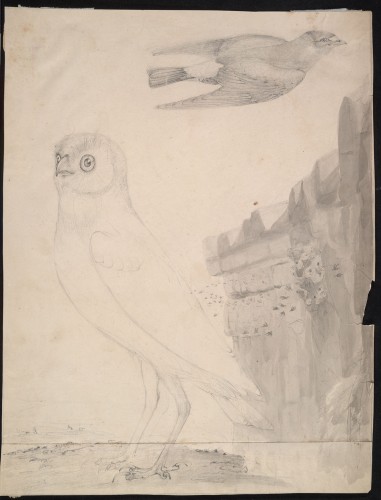

Titian Ramsay Peale sought to organize his experiences in an unfamiliar natural world through art. His initial sketches record raw information gained in the field, including both an animal’s appearance and its behavior. More finished studies were used to refine the animal’s appearance. Rather than offering a portrait of an individual, Peale wanted to record the characteristic or ideal qualities of a whole species. Finally, he brought together his concrete field observations with the idealized specimen image to communicate an entire species’ appearance and behavior. As he moved from the chaotic initial sketch to an orderly finished product, he asserted control over unwieldy nature.