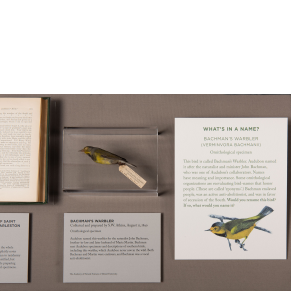

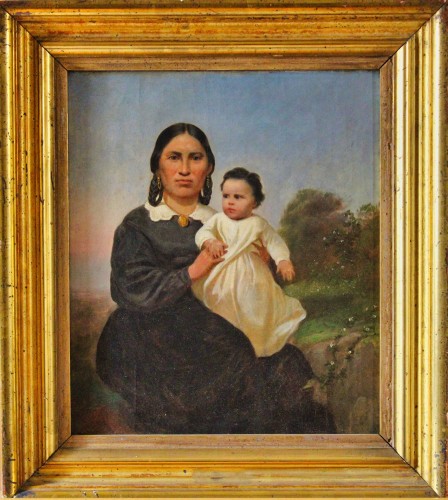

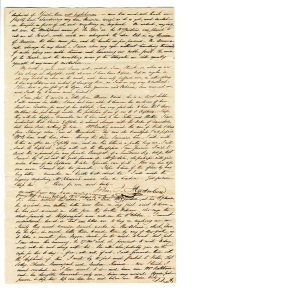

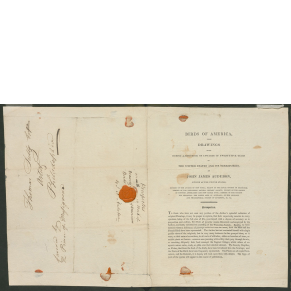

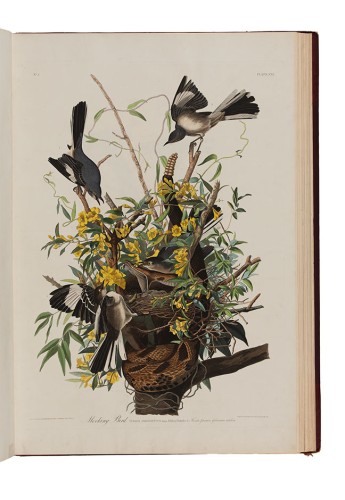

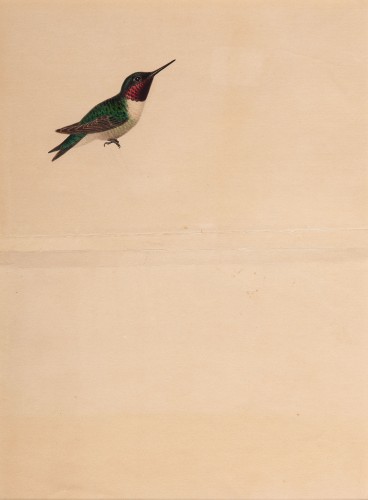

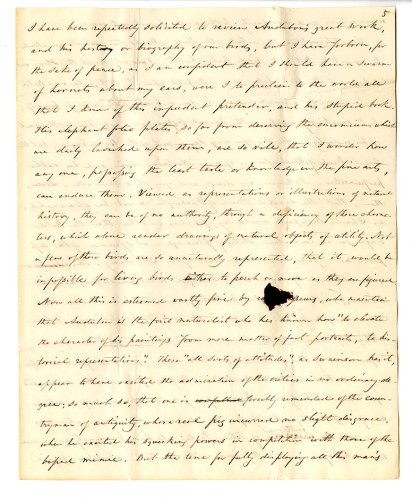

John James Audubon was an outsider who struggled to gain acceptance from Philadelphia’s naturalist community. In Birds, Audubon departed from the strict taxonomic approach advocated by professional naturalists. Instead, he staked his reputation on a commitment to unsurpassed fieldwork. To capture the American wildlife he observed firsthand, he showed active birds interacting with one another and their environments. These multi-figure compositions combined designs from contemporary painting and traditional scientific illustration. Audubon also infused his illustrations with drama to express the emotional life of animals. Audubon claimed these designs were totally original, but he built on clear precedents in the work of earlier naturalists.

John James Audubon: The ‘Universe’ of America

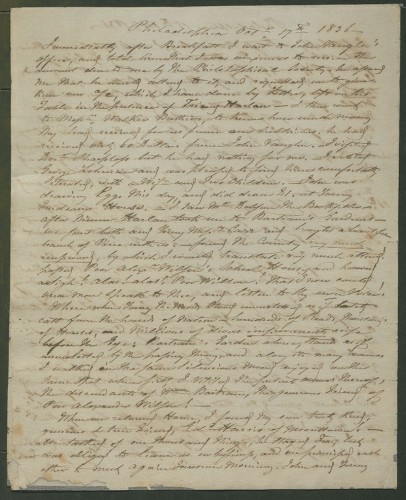

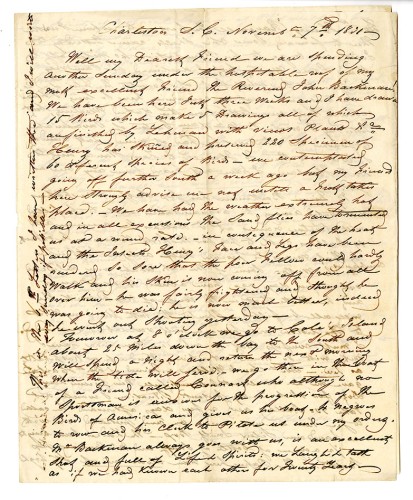

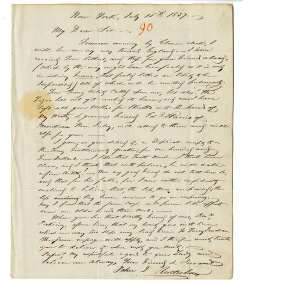

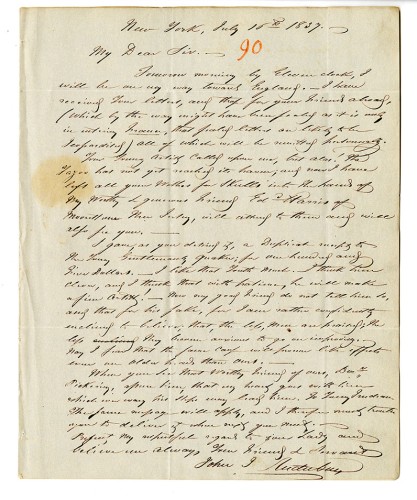

John James Audubon (APS, 1831) was born in the French colony of Saint-Domingue (modern Haiti). He came to the United States in 1803, where he cultivated an interest in ornithology. Audubon’s The Birds of America (1827-38) is best known for its dramatic representations of American birdlife. Audubon introduced multi-figure compositions that captured birds' environments and complex social lives. These vivid images of American wildlife intensified the identification of the United States with its natural splendors. But these images also laid intellectual claim to the land as Native Americans faced increased dispossession in the 1820s and 1830s. Further, they romanticized landscapes that supported plantation slavery. Audubon supported these policies both as an enslaver and as a participant in scientific racism.

A Bird’s-Eye View

Landscapes of Change

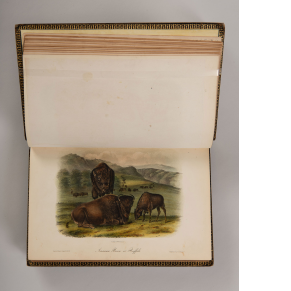

The Quadrupeds of North America (1845-1848) was John James Audubon’s last major project. His health was failing and much of the work would be completed by his two sons and his collaborator, John Bachman. Work began at a time when human-caused environmental change had accelerated in North America. A large number of images in Quadrupeds depict environmental destruction, as animals are haunted by fields filled with tree stumps and fences. Audubon rarely, however, protested environmental destruction in public. He was also quick to justify his own hunting—up to one hundred birds per day in the field—as necessary death in the pursuit of science.

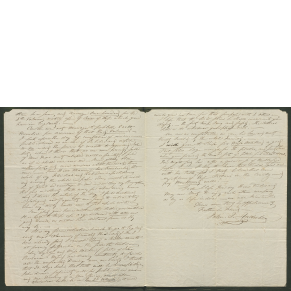

Audubon’s Unacknowledged Collaborators

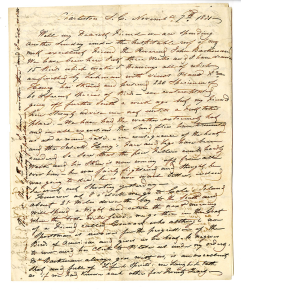

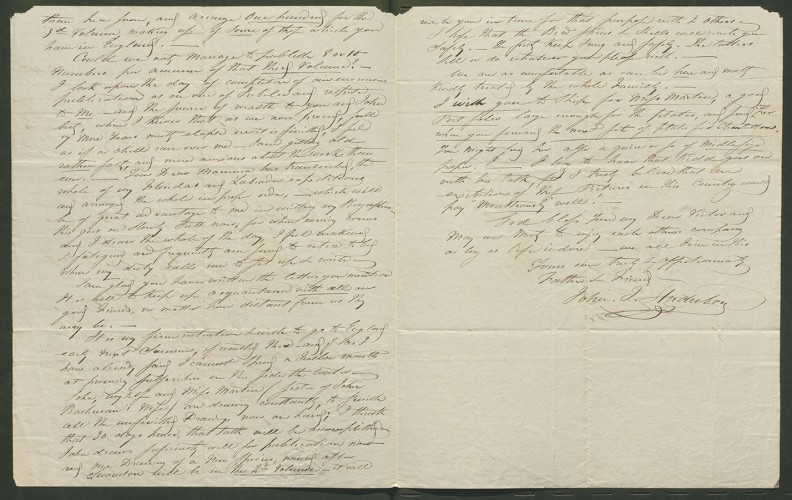

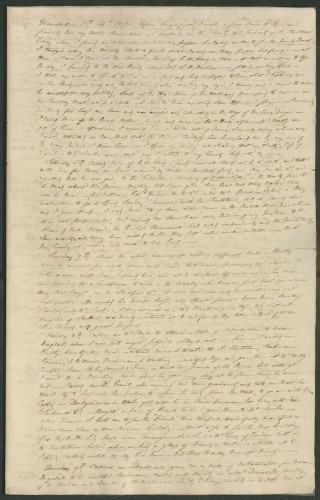

The Birds of America and Quadrupeds of North America were collaborative projects. They required observing animals across North America, producing thousands of images, and writing volumes of text. Among Audubon’s collaborators were many women, Native Americans, and African laborers who made Audubon’s work possible. Maria Martin, the sister-in-law and later wife of Audubon’s collaborator John Bachman, produced botanical images for many plates in Birds. A man named Thomas, whom Bachman enslaved, taxidermied specimens during the years Audubon collaborated with Bachman on Birds. Finally, Natoyist-Siksina’ (Medicine Snake Woman) was a Kainai woman who helped facilitate the multiracial knowledge networks on which Audubon relied.

![Mastodon tooth [molar], crown view](/sites/default/files/styles/item_detail_carousel/public/2025-03/90--cat79--Mastodon-Molar%2C-Crown-View.jpg?itok=NZSglz4A)