|

Title page of William Stork's

Description of East Florida |

For the APS, the value of William Stork's

Description of East-Florida lies as much in containing the first appearance in print of the journal of John Bartram (1699-1777) as it does in the quality of Stork's prose. Born in Marple, Pennsylvania, John Bartram was raised a Quaker, and while he dissented from the Friends' pacifism and theology, he was deeply influenced by their world view and used Quaker religious connections to further his career. Possessed of a very limited formal education that featured only the tiniest smattering of Latin and inadequate attention to the rules of grammar, John so prospered as a farmer that before he had turned forty, he was able to devote significant attention to his true love: natural history. Under the patronage of James Logan and later Benjamin Franklin and Peter Collinson, Bartram pieced together a rudimentary technical knowledge of botany and during the late 1730s and early 1740s, began on a succession of botanizing tours of the middle colonies, beginning with a trip up the Schuylkill River, and later venturing into the Blue Ridge Mountains, along the James, Susquehanna, Hudson, and Mohawk Rivers, and into the Catskills. A journal kept while accompanying Conrad Weiser on an expedition to treat with the Iroquois nations at Onondaga, New York, became Bartram's first publication,

Observations on the Inhabitants, Climate, Soil, Rivers, Productions, Animals, and Other Matters Worthy of Notice (London : Printed for J. Whiston and B. White, 1751).

|

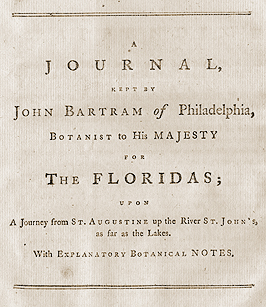

Start of John Bartram's journal

(click to read entries for December 24-25, 1765) |

First and foremost, Bartram was a supplier of raw materials to the scientific elite of America and Europe, and he was very successful at it. By 1740, he had attracted international note for his skill in procuring native plants for the gentlemen of Europe. As a scientist and merchant, horticulturist and supplier of natural objects, Bartram assembled a lucrative client base, including his patron, Peter Collinson, the Dukes of Bedford, Norfolk, and Richmond and a smattering of Earls and lesser nobility. At his

gardens in Kingsessing (now south Philadelphia), he grew dozens of species of trees, shrubs, and other plants collected on his travels, and experimented with hybridization and the selection of cultivars to meet, and sometimes create, a demand abroad for exotic plants. Interested equally in the ornamental, medical, and agricultural uses of plants, Bartram established the finest botanic garden in all America during the colonial period.

Bartram is remembered as well for his role in fostering the growth of scientific institutions in British North America, most notably the American Philosophical Society. Hoping, in part, to bolster his credentials in European eyes, he suggested to Collinson that an American counterpart to the Royal Society be established where the educated and engaged members of colonial society could meet to promote "useful knowledge." Although Collinson's reply was cool, even dismissive, Bartram held on to the idea until he met with more receptive ears. In 1743, the ever-energetic Benjamin Franklin seized upon the plan and along with Bartram, formed the first American Philosophical Society.

Bartram's scientific and commercial endeavors flourished in the 1750s and 1760s, his botanical supply business providing the income and incentive to enable him to travel ever wider in search of new specimens. In 1765, the aging Bartram set sail from Philadelphia to join his son, William, in Charleston to begin a botanical and scientific survey of the South. From Charleston, they traveled overland to Saint Augustine and Fort Picolata on the Saint John's River, and from there, by canoe and foot throughout the extensive drainage basin.

|

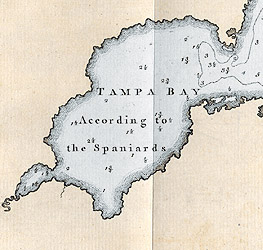

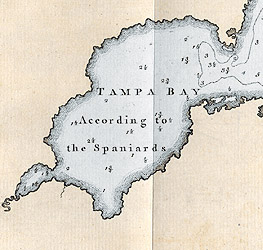

Map of Tampa Bay

(click to see complete map of Bay of Espiritu Santo |

Like many natural histories, Stork's tract is part promotional, part natural historical. A knowledge of flora and fauna was essential for successful -- and profitable -- settlement, and writers and land owners stood to profit personally from an increase in interest. Adding to a promising description of Saint Augustine, and chapters on the climate, soil, and animal and plant life, Stork included bullish tracts on the potential in Florida for the cultivation of rice, cotton, silk, sugar, indigo, and other profitable crops. On the same latitude as the productive English colonies in Bengal and China, the warm climate of Florida made silk culture particularly likely, whereas in "Carolina and Georgia the worms are often injured by accidental frosts."

The development of the colony, however, clearly depended upon slavery. Governor James Grant's proclamation promoting European settlement gave a clear advantage to the slave holder. Grant decreed "That 100 acres of land will be granted to every person, being master or mistress of a family, for him or herself; and 50 acres for every white or black man, woman or child, of which such person's family shall consist, at the actual time of making the grant." In the same appendix, Stork included a letter from a South Carolinian whose plans were even more revealing: "I shall return to East-Florida next November, and carry negroes with me; as the governor will not grant us our land, till the negroes are arrived in the province."

The APS copy of Stork's Description is the third edition of 1769 (the first two were issued in 1766), which includes Thomas Jefferys' maps of East Florida and the Bay of Espiritu Santo, and his plan of Saint Augustine, none of which were included in earlier editions.