David Center for the American Revolution Seminar: “To Husband a Better Liberty: The Constructive Widowhood of Jane Martin Bartram, c. 1790-1815,” with Wayne Bodle

The third 2022-2023 David Center for the American Revolution Seminar will take place January 25, 2023 at 3:00 p.m. ET on Zoom.

The speaker will be Wayne Bodle. Dr. Bodle is retired from a 25 year teaching career at Penn (his doctoral academy), Iowa, Rider, and for almost twenty years, Indiana University of Pennsylvania. He has been affiliated with the programs of the McNeil Center at Penn since 1985, and held fellowships from the APS and Library Company, among others. His research interests include war and society, the regional character of the Middle Atlantic colonies and states, and women and gender. His book, The Valley Forge Winter: Civilians and Soldiers in War, (Penn State, 2002) is still in print, earning tiny royalties but hoping for better in the 2026 “Sestercentennial.” In 1987-88 he was half of the first ever David Library fellow (long story) co-tenable in Washington Crossing and Penn. His principal current project traces the life of Charles Wollstonecraft, the youngest sibling of the feminist philosopher, Mary, in America from 1792 until 1817, and the much longer careers of his first and second wives, his daughter, and a few other figures, mostly women, until the eve of the Nineteenth Amendment. Today’s paper not-quite-fits any of these categories, but it hopefully completes a side-project from his year as a David Fellow.

Wayne will be presenting his paper, “To Husband a Better Liberty: The Constructive Widowhood of Jane Martin Bartram, c. 1790-1815.”

A description of the paper is below. The paper will be pre-circulated to registered participants in advance of the seminar meeting.

To attend the seminar and to receive a copy of the paper, please register via Zoom.

The David Center for the American Revolution Seminar serves as a forum for works-in-progress that explore topics in the era of the American Revolution (1750-1820). Questions about the series may be directed to Adrianna Link, Head of Scholarly Programs, at [email protected].

NOTE: Seminars are designed as spaces for sharing ideas and works still in-progress. For this reason, this event will not be recorded.

“To Husband a Better Liberty: The Constructive Widowhood of Jane Martin Bartram, c. 1790-1815”

In 1987-88, while serving as the first fellow of the David Library (co-tenable that year at the Philadelphia Center for Early American Studies), I “met” two figures; one in-person, Linda Kerber, around a seminar table in Philadelphia, and the other, Jane Bartram. (1743-1815), virtually, as I cranked microfilm in Washington Crossing. Without pausing my official project-of-record on the Continental Army at Valley Forge, and under the generous tutelage of Professor Kerber, I explored questions raised by Jane Bartram’s life as the assertive wife a Pennsylvania Loyalist refugee who rejected both his political definitions of their marriage and the (supposedly) “radical” state of Pennsylvania’s crabbed vision of her relationship to the republic itself. Learning more about these things in a “pre-internet” search world that I can almost credit now, I wrote a paper for a conference at the Center, and soon thereafter, published a revised version in the Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography.

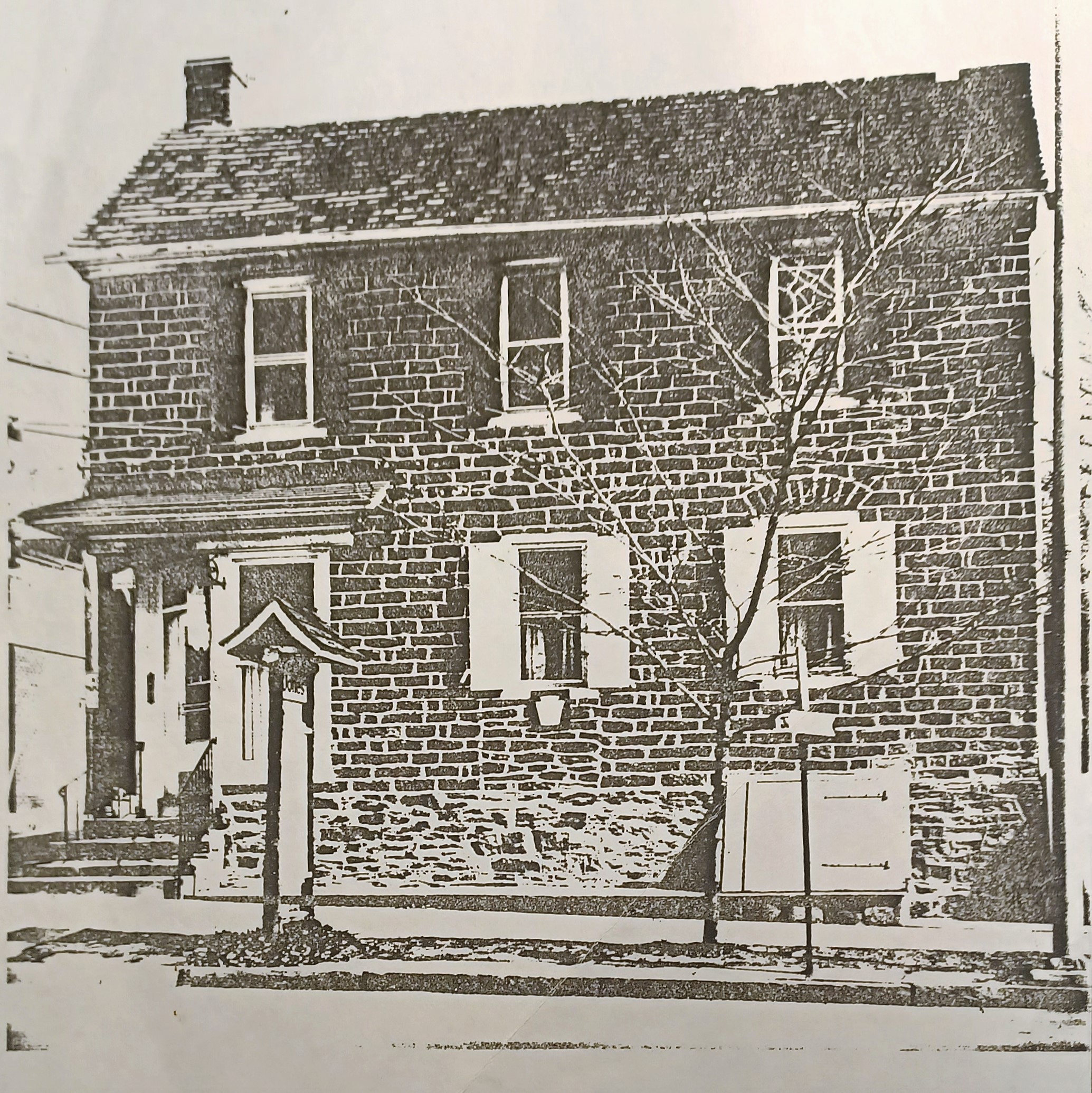

Given editorial space limits and rapidly evolving historiographical understandings of gender, I could only “write” Bartram’s story to her recovery of autonomous public and private life in 1790, but I promised to revisit paradoxes raised by her subsequent experience if and when that became possible. After persuading Pennsylvania authorities to let her return from politically imposed exile in New York, and maneuvering her estranged spouse into sharing his compensation award from the British crown, Jane reopened their housewares store in Philadelphia in the 1790s while judiciously accumulating house lots in Southwark on which to collect ground rents as a stable form of eventual pension income. In 1793, she moved with her young and possibly disabled son to Newtown, the bustling new seat of Bucks County, where she resumed mercantile life and expanded her real estate investing. During the last decade of her life (1805-1815) she adopted more prudent fiscal retirement strategies, selling the Newtown properties just before the county seat moved further inland to Doylestown, and relying on the growing value and cash-generating capacity of her Philadelphia portfolio for her basic livelihood.

I (naively) imagined Bartram as an American avatar for Mary Wollstonecraft, but accumulating research rendered that interpretation tenuous. Now, after studying actual Wollstonecrafts in America (Mary’s brother Charles, his two wives, and a daughter from his first marriage) I hope to give Bartram the rest of her life back in print. Though more tempered and conservative than Wollstonecraft and her finite band of American female devotees, Jane navigated boldly and effectively a wide range of post-backlash,male-dominated, public and private realms. She reconciled with the Quaker elders who had disowned her for marrying a Presbyterian Scots immigrant, Alexander Bartram. At her death she left part of her estate to her grandson, Alexander James Bartram, deeming him not the offspring of her son, James Alexander Bartram, but of her daughter-in-law, Ann Nicholson Bartram. That act may not have “said it all” about her later-in-life gender evolution but it surely said something. She also revised public understandings of her relational identity. She briefly and futilely sought a legislative divorce in 1785 from the politically discredited Alexander, but after their compensation agreement she comported in Newtown as “The Widow Bartram.” Little evidence has emerged about Alexander’s life or death in Nova Scotia, but she did quite well for herself for someone traumatically orphaned at the age of five.