|

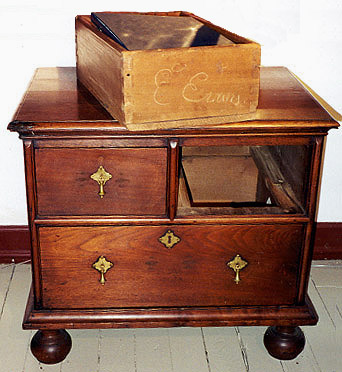

Fig. 1: The "Franklin table," attributed to William Savery

Private collection, Philadelphia |

Concealed from public view for most of its existence, the account book had descended through seven generations of Quaker relations. It was donated, in 1991-1992, to the American Philosophical Society, as part of an extensive collection, the George Vaux Papers.4 The account book's significance, however, was not discovered until May 7, 1999, during research on other material in that archive. The subjects of that inquiry were two pieces of furniture that had descended in the Vaux family. One was a curled maple, intaglio-knee dressing table with a Benjamin Franklin provenance, and attributed to the shop of William Savery [Fig. 1].5 The other was a curled walnut, slant-front desk on ogee bracket feet with serpentine interior, which had been originally owned by John Head, Jr., one of Philadelphia's wealthiest merchants at the time of the Revolution [Fig. 2].6

|

Fig. 2: The desk of John Head, Jr.

Private collection, Philadelphia

|

John Head's will, proved October 18, 1754, identified him only as "Joyner." His furniture was referenced solely in terms of its disposition with other of his household goods. Only one article of furniture was even mentioned, "a Clock & Case." Regrettably, the originals of Head's will and probate inventory are lost. Nor were they preserved on microfilm, as the Register of Wills's microfilm of early wills and inventories indicates that they were determined lost as of the time of filming. All that survives of Head's will is the so-called "Index copy," the contemporaneous transcription made for the Register.9 The original or a copy of the probate inventory appears to have been extant circa 1964, when it was cited, as follows: "A joiner, John Head, whose inventory was taken by two fellow joiners, Thomas Maule and Joseph Chatham, on November 11, 1754, possessed fourteen rush-bottom chairs valued at three pounds two shillings."10

Unlike many other Philadelphia joiners, Head's name did not appear as an appraiser of probate inventories. (Presumably, joiners were chosen for such tasks because of their familiarity with furniture, often the costliest asset in an estate. At other times, they may have been picked because their work related professionally to that of the decedent.) Nor was Head's name among those known to have been admitted as freemen of Philadelphia.11 Nothing in other public records readily suggested the extent of Head's business dealings or his property holdings.12 The only reference to him in contemporary Philadelphia newspapers was a posthumous one, to a lot of ground he had owned while alive.13

Secondary sources provided little more. In Hornor's Blue Book, Philadelphia Furniture, John Head was but one of a hundred joiners, chair-makers, turners, and cabinetmakers, listed as working during the period 1682-1722. Head was accorded only a single line: "John Head, joiner, removed from Mildenhall, Suffolk, England, 1717; died 1754."14 No citation for such information was given. Nor was there any indication as to what Head produced, to whom he sold it, or his relative importance to other Philadelphia cabinetmakers.

In the articles of The Pennsylvania Genealogical Magazine, John Head was identified once, as a "joiner of Philadelphia," but only in his capacity as father-in-law to the prosperous Revolutionary merchant Jeremiah Warder, nothing more.15 Indeed, in a pamphlet history of the Warder family, while mention was made of his mercantile stature, John Head was not even identified by name: "Jeremiah [Warder] married Mary Head, the daughter of a leading merchant of Philadelphia."16

No reference whatever may be found for John Head as a joiner, either in on-line genealogical databases, or in the relevant volume of that monumental compendium of early Pennsylvaniana, Lawmaking and Legislators in Pennsylvania, A Biographical Dictionary.17

Once within the George Vaux Papers, further biographical detail begins to emerge. Family trees prepared by George Vaux VIII show John Head as born in England on April 8, 1688, the son of "Samuel (?) Head" and "Sarah Jackley(?)." In 1717, Head was "of St. Edmondsbury," a reference to today's Bury St. Edmunds, Suffolk. Head married "Rebecca Mase," at "Baybon Suffolk England 3/15 1712." Rebecca was listed as born in England in 1688, and dying in Philadelphia "6/4 1764."18

Vaux's information appears to have come from John and Rebecca's marriage certificate. The original certificate was in his possession on November 28, 1874, when Charles Caleb Cresson called at his office, at the back of 1700 Arch Street, according to a November 30, 1874 letter from Cresson to Thomas Stewardson. Cresson enclosed for Stewardson his "memoranda," based on that certificate and other information given him by Vaux. They clarify and expand upon Vaux's genealogical data. Cresson noted that the marriage took place at the "Meeting place at Bayton (or Baybon) [on] the 15th of 3 mo. (May) 1712." Whereas there is no "Baybon," the seat and parish of "Bayton," or "Beyton" as it is sometimes spelled, does show up on Suffolk county maps approximately 5 1/2 miles east of Bury St. Edmunds. Thus the marriage took place in a Quaker house of worship in that town. Cresson further noted that the newlyweds were described as "John Head of Edmonsbury - in the County of Suffolk, Joyner, and - Rebekah (she signed Rebeckah) Mase - daughter of Richard Mase - of bury aforesaid."19 Thus Head must have completed his apprenticeship by the time of his marriage. As both he and Rebekah were of Bury St. Edmunds and their marriage had taken place nearby, this suggests that Head practiced joinery and underwent his apprenticeship in Suffolk, in or around Bury St. Edmunds.20 A search of the records of the Joiners' Company of the City of London has turned up no record either of his having been bound as an apprentice there or admitted to the freedom of the Company.21

An endorsement on a fold of the marriage document, "John Head - 8 day of 2 mo. 1688," was Vaux's source for Head's date of birth, April 8, 1688. Other endorsements on another fold gave [birth] dates of "1 mo. 1 1713," March 1, 1713, for Rebecca, and "14 of 2 mo. 1714," April 14, 1714, for [their daughter] Mary. Cresson's remaining "memoranda" regarding the joiner cast light on his arrival in Philadelphia and where he lived: "The first John Head - had 11 children - 4 at the time he landed at Philad.[,] the two youngest he & his wife carried in a tub from the landing to their dwelling - means of conveyance being scarce in those days -*** J.H. lived and died - on the N. side of Arch St. - 40 ft. E. of 3rd - lot 20 x 110 - his house is gone - [.]"22

A bit more information about Head was mounted inside the cover of his account book, in a typescript, signed "George Vaux [VIII]," and dated March 1, 1904:23

This book is mainly in the hand-writing of John Head who was born in England, in 1688, married there in 1712, came to America in 1717, and died in 1754. There is reason to believe that he was a minister among Friends, but if not[,] certainly an elder. By trade he was a cabinet maker. His son John was my maternal great-grandfather, and one of the few wealthy merchants in Philadelphia before and at the time of the American Revolution. His second daughter Mary, my paternal great-grandmother was the wife of my paternal great-grandfather, Jeremiah Warder, also a wealthy merchant at the same period. His oldest daughter Rebecca was an ancestor of Johns Hopkins who founded the great University and Hospital in Baltimore, which bears his name. Another daughter was ancestor of Chief Justice Sharswood, of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, and still another was ancestor of the Cresson, Biddle and Garrett families in Philadelphia.Many of the most prominent Friends families in England were descended from his brother and probably his sister.24