William J. Robbins: A Second Look

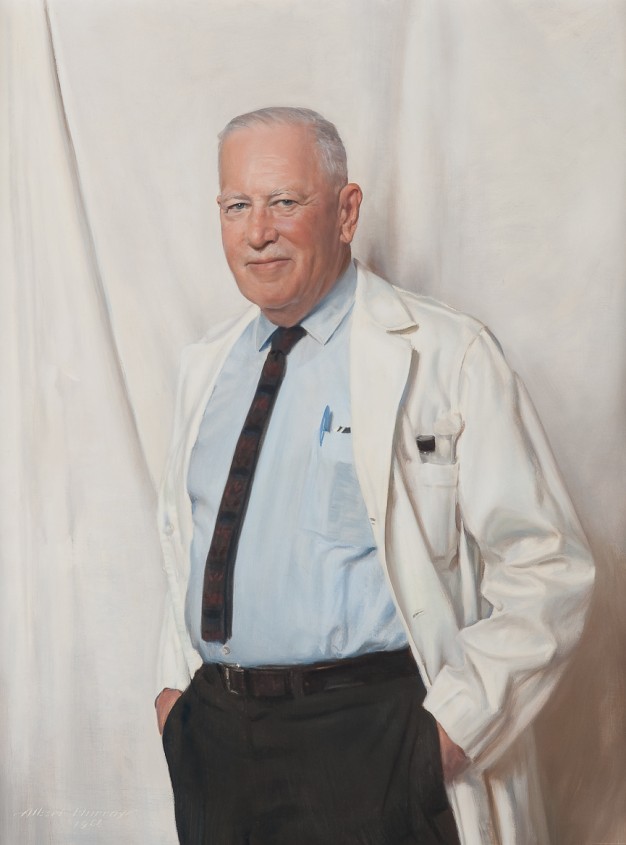

Portrait of William Jacobs Robbins by Albert Ketcham Murray, 1966, APS Collection; Robbins is the only Executive Officer to be pictured in his lab coat

As I put finishing touches on the Executive Office records, I realized that I had neglected to write about William Jacob Robbins (1890-1978), the American Philosophical Society’s third Executive Officer. At first glance, Robbins is a figure who is easy to overlook. His tenure as Executive Officer was relatively short, from 1959 to 1960. He also left behind the smallest group of EO records, measuring just five linear feet. Even Edward C. Carter, II neglected to mention Robbins in his book, “One Grand Pursuit”: A Brief History of the American Philosophical Society’s First 250 Years, 1743-1993.

In giving Robbins a second look, I’d like to provide some additional insights to show the importance of context with archival materials, as well as narrative threads that exist both inside and outside of APS, which deserve further investigation whenever time allows.

This assignment was welcome, because when I processed Robbins’ subseries, I pondered how to best characterize the documentation. His correspondence seemed to be intermingled with that of his predecessor, Luther P. Eisenhardt (APS 1913), and his successor, George W. Corner (APS 1940). Since I was doing minimal processing, I didn’t have the luxury of doing a deep dive into his records. I characterized his series as “transitional,” because that’s what its mixed state was telling me.

Even with minimal processing, archivists follow tried and true principles, which are the cornerstones of our profession. Regarding the issue of provenance, it seemed like the three administrators were trading off responsibilities at the time. As for original order, it looked like this was how the records were originally organized by Julia Noonan (longtime secretary and developer of the Executive Office’s file plan), so the arrangement didn’t appear to be by accident. Of course, the other question that arose is why, since other Executive Officers had longer and more definite terms of service.

I was familiar with the basic facts of Robbins’ involvement with the Society. He was elected as a Member of the Society in 1941. Prior to becoming an Executive Officer, Robbins served as President from 1956 to 1959. This in itself is distinctive, because the only other EO to serve as President was Edwin Conklin (APS 1897).

Notably, Robbins’ involvement with APS happened when he was still serving as Director-in-Chief of the New York Botanical Garden (his records there have been processed and are available for research). A botanist by training, he provided leadership at NYBG from 1937-1958, a tenure made more remarkable in that it was his second career.

Robbins got his professional start in academia, which included a long stint at the University of Missouri from 1919 to 1937. One of his noteworthy hires was Barbara McClintock (APS 1946). This was part of a larger pattern of him mentoring colleagues and proving valuable support for those coming up in the field. It can be said that Robbins influenced a generation of scientists in the early 20th century, through his lectures in the classroom, involvement with professional organizations, advisory work with grant agencies, and numerous publications. Many of his books, articles, and other printed materials can be found in the Library’s online catalog.

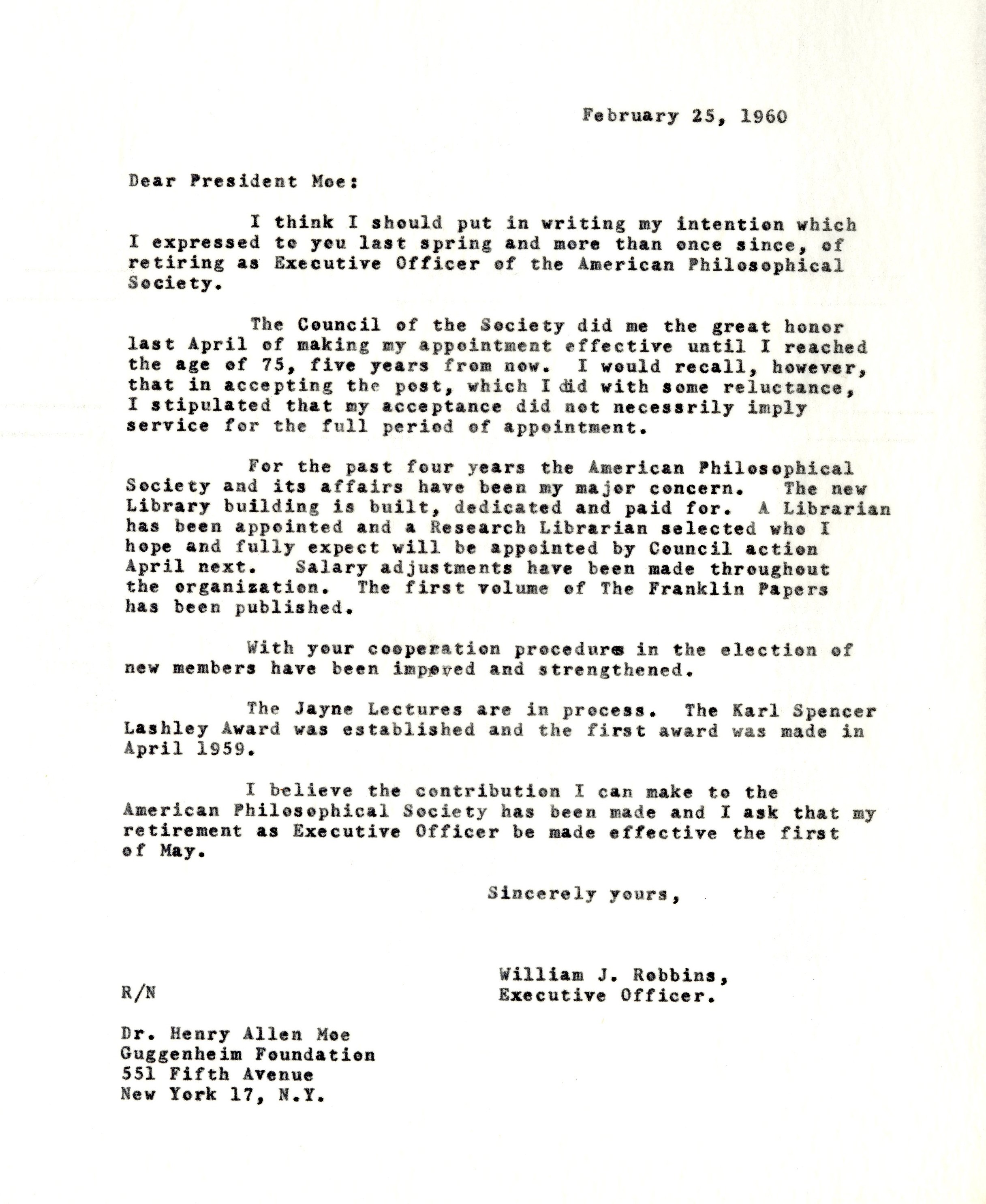

As I delved deeper, I found Robbins’ National Academy of Science memoir from 1991 to be particularly illuminating. It shed light on an exchange that I had come across in his EO files, which puzzled me. Given the passage of time, the memoir’s authors felt it was acceptable to discuss a life event that affected Robbins’ time at APS: he was diagnosed with lung cancer. Needless to say, it changed everything. He retired from NYBG and sent the following letter of resignation to Henry Allen Moe (APS 1943), who succeeded Robbins as APS President just months before:

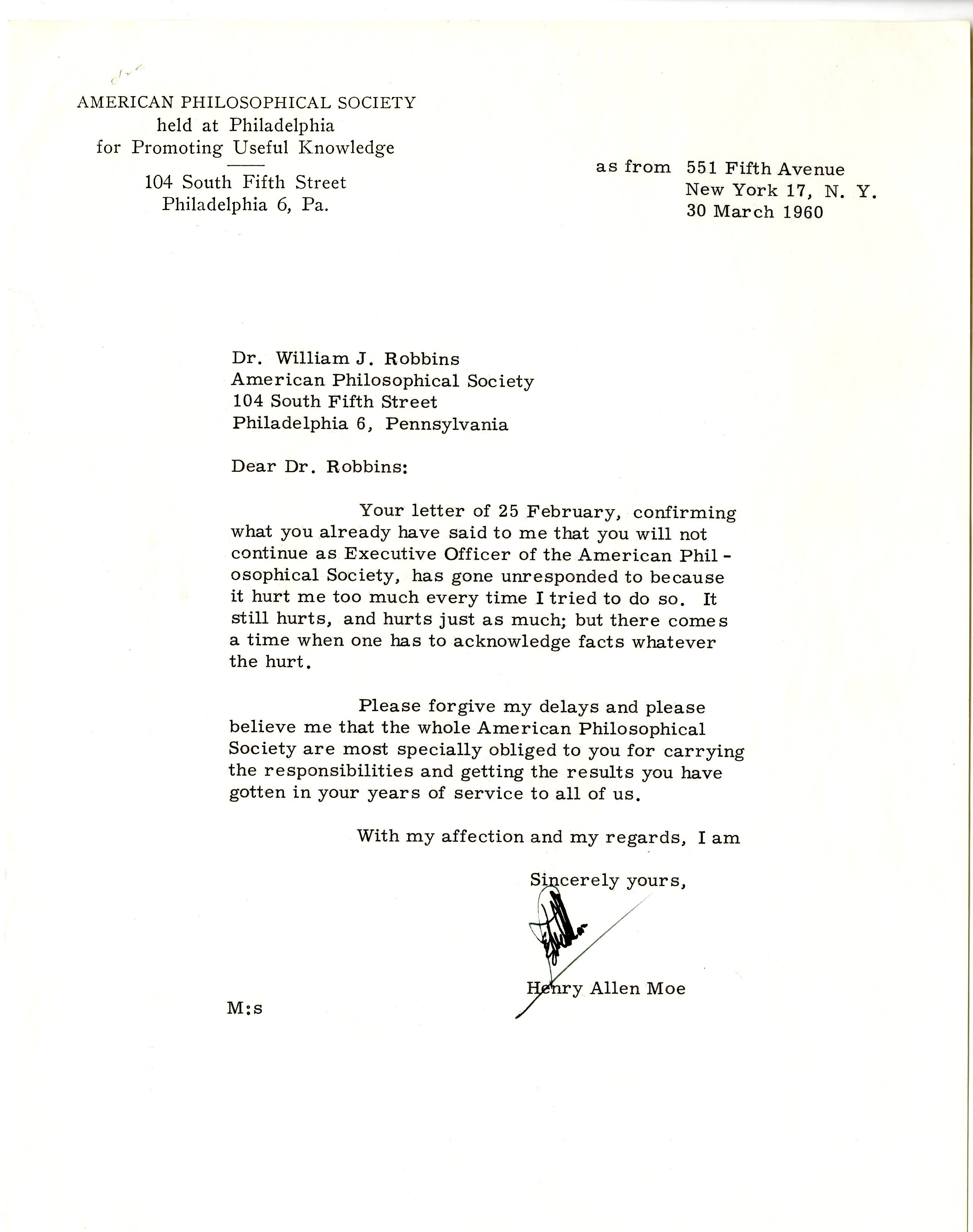

In return, Moe sent the following acknowledgment, which conveyed both warmth and empathy. It expressed an understanding between them, as friends and colleagues.

This is a good example of there being more to institutional records than what initially meets the eye. While administrators in the 1950s may have been reluctant to openly discuss personal matters, one can still get a sense of the poignancy of the exchange, given enough information to understand the context of the letters and the gravity of the situation.

Fortunately, Robbins defied the odds and lived for another twenty years. After his retirement, he decided to set up a lab at Rockefeller University, which was a sound choice; he continued the research that was a constant throughout his professional career. As his NAS colleagues mentioned in a bittersweet note, Robbins was conducting experiments up until the day before he died in 1979.

In taking a second look at resources related to Robbins, I’m glad that what I’ve discovered supports my initial processing decisions with “More Product, Less Process,” or, MPLP. Further, these materials provide a window into the broader narrative of his life, career, and personal character. Far from being dry and routine, the Society’s records hold many compelling stories like these, for anyone who is willing to look, piece together the clues, and gain a better understanding of our institutional memories.