Traces of Heterodoxy in the Elsie Clews Parsons Papers

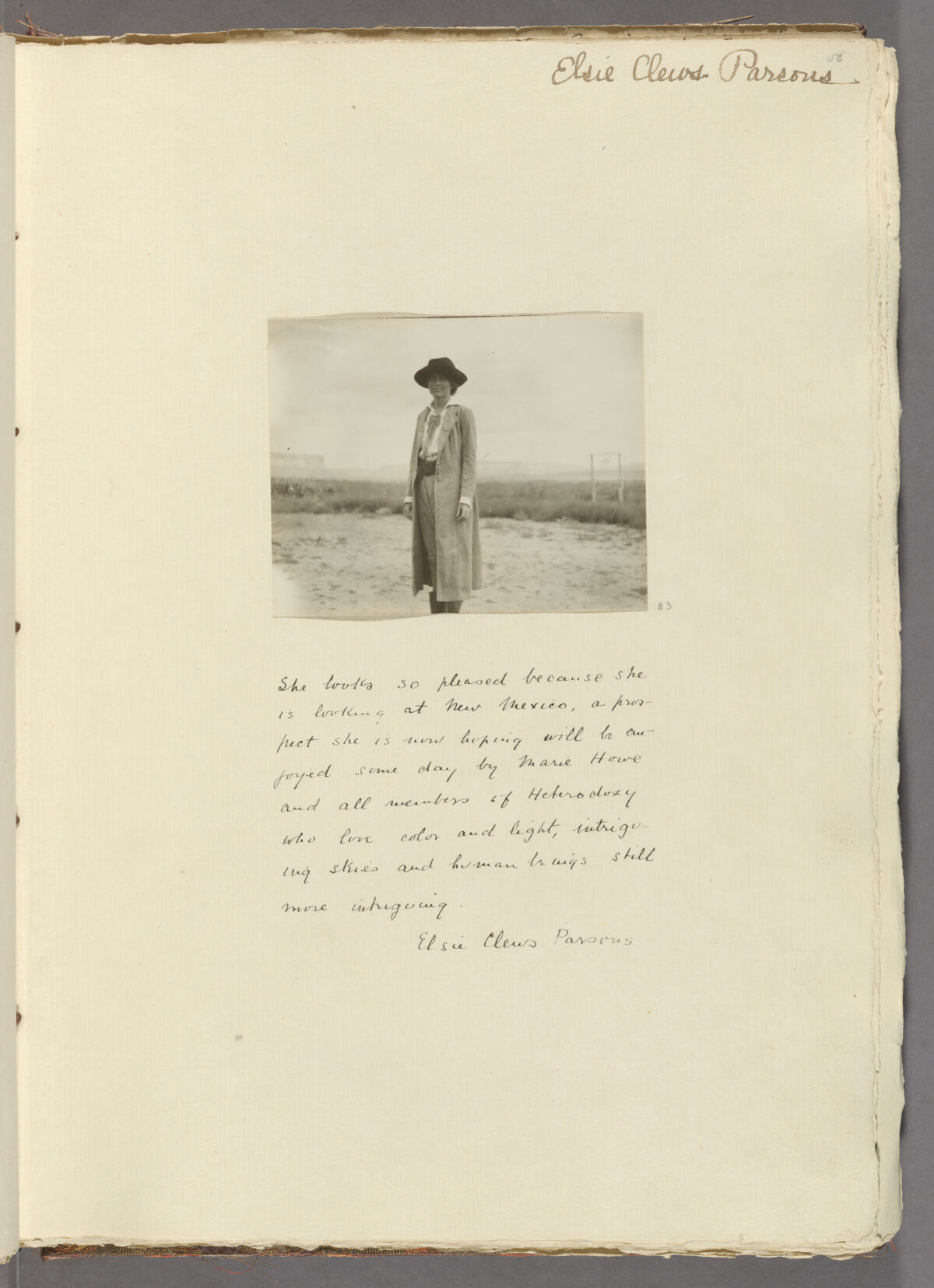

Header Image: Elsie Clews Parsons, photographer unknown, n.d. “Parsons, Elsie Clews #6 [3 prints; 2 neg.] ca. 1913,” Box 2, Series VIII, ECP2, APS.

Elsie Clews Parsons became an anthropologist and a feminist in tandem. Already with a doctorate in hand, Parsons first tried on an identity that did not fit. She performed the role of political wife while Herbert Parsons served in the House of Representatives (1905-1911). This position, however, enabled her to take a first ethnographic tour in 1905, accompanying a congressional party with Secretary of War William Howard Taft to the Philippines and Japan. The next year, she lost her third child days after the birth and rocked the Washington establishment when publishing, The Family, a textbook that fueled controversy because of its endorsement of trial marriage.

That this first fieldwork preceded Parsons’ first public explanation of how “the personal is political” is not a coincidence. During a month-long residency at the American Philosophical Society in May, I poured over Parsons’ unpublished manuscripts and correspondence to draw a clear link.

My interest in Parsons stems from my interest in Heterodoxy, a secret feminist society that met every few weeks around Greenwich Village for nourishment through food and frank talk between 1912 to the early 1940s. Heterodites, as they called themselves, wanted the freedom to commiserate about difficult bosses, vexing children and lovers, and deferred ambition beyond a hushed whisper. For this reason, they had a golden rule: no minutes and no media leaks. As a result, Heterodoxy remains a historical enigma.

Looking at the lives of a few Heterodites in close range allows a better understanding of how Heterodoxy became a hub of American feminist thought and action with reverberations of impact across every major U.S. social movement in the 20th century. Parsons’ interest in feminism and anthropology predated her involvement in Heterodoxy, but the group bolstered her insistence that a feminist worldview must be a central tenet in cultural anthropology.

Before Heterodoxy, Parsons yearned for a space to discuss how her life shaped her intellectual ideas. One of the gems I found in the APS archives was a fragment of a note that likely became a speech to a scholarly audience of primarily men. In late 1906, she reluctantly shared, “at the risk of incurring…criticism,” what she had faced in recent months. “Last year my two days old baby died,” she revealed, “I am convinced that had I not been able to during convalesce under these trying circumstances to think and write at first for a few minutes each day and then for a few hours about a scientific subject in which I had been much interested, return to a happy and normal life would have been far slower.” It is this kind of introspective testimonial followed by intellectual and political dialogue that was uniquely the stuff of Heterodoxy meetings and not so welcome in professional circles.

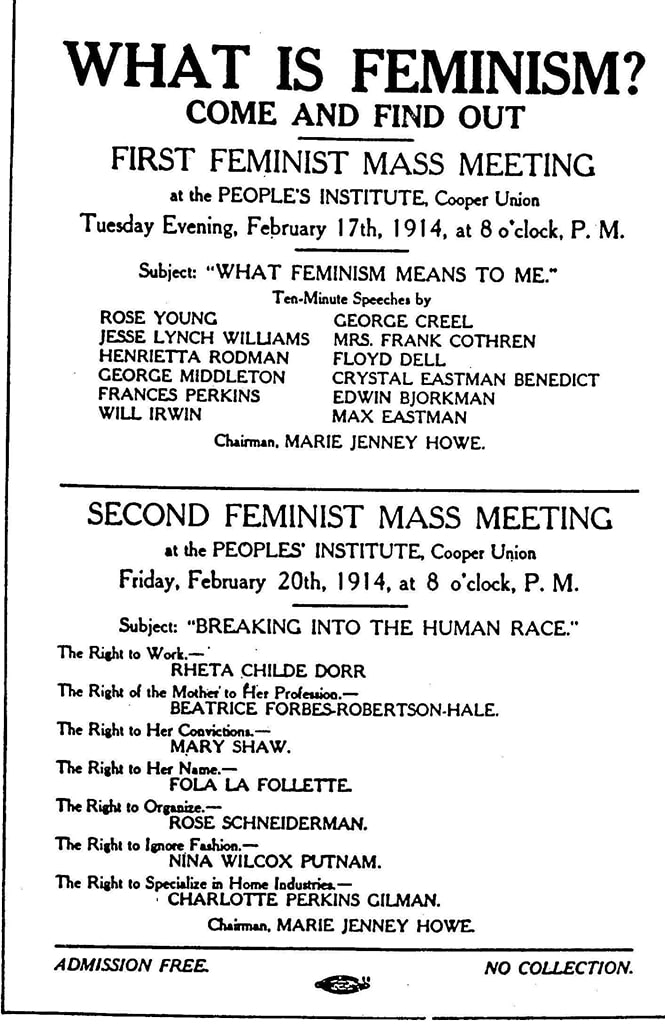

Parsons joined Heterodoxy around 1913, an affirming decision she wrote about in the unpublished semi-autobiographical, “The Journal of a Feminist.” At one point, she mentioned with glee, “I am going to a talky-talky dinner tonight on mother’s pensions.” In another instance, she reported, “I went last night to what its promoters advertised as the ‘first feminist mass meeting.’ The woman question or women’s rights we have had with us for some time, a hundred years or so, but feminism, it seems, is quite new.”

Parsons was active in Heterodoxy at least until 1938. Very few of her appointment books have been preserved. However, one from that year remains because she documented an especially memorable summer cruise of the Greek islands. Parsons also noted her plans to attend a mid-March Heterodoxy meeting. While only traces of Heterodoxy appear in her vast archive, the imprint is clear throughout the full corpus of her prolific anthropological, philosophical, and creative works, published and unpublished. As she wrote in her 1914 article, “Feminism and Conventionality,” “Rarely indeed do women go off by themselves.”