Step Away from the Tape (Again)

You may remember Renee Wolcott’s excellent blog post that addressed why we conservators (and all of us library, archive, and cultural heritage professionals) abhor any type of repair strip that uses pressure-sensitive adhesive. Tapes do seem to supply an easy fix to those pesky tears that arise in our daily lives. The operative word here is “seem,” if this hasn’t been made obvious.

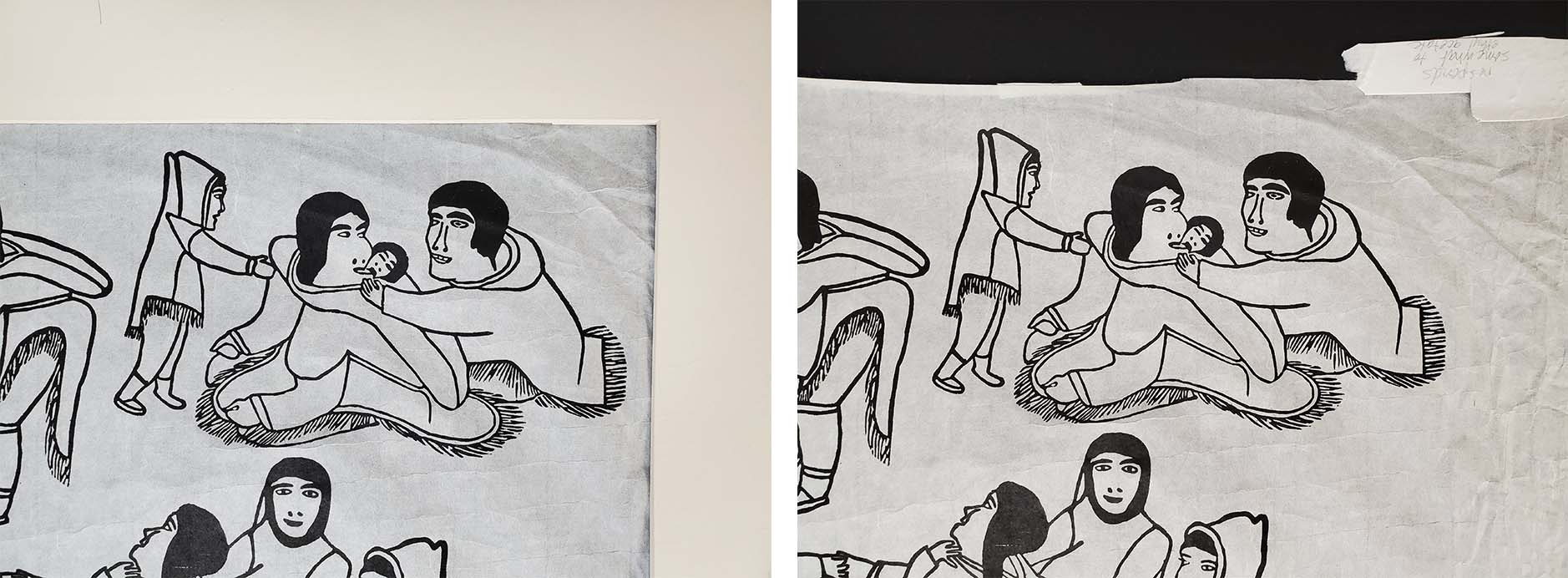

One conservation project’s tape removal “haul” may be fruitful (and satisfying in the results) when the paper from which the tape is being removed is very smooth, and readily releases the tapes with heat. In an instance like this, it’s easy for a conservator to quickly remove yards of tape. A tape removal project I’m about to undertake doesn’t, however, inspire that level of confidence in me. I know I will find a way to remove the tapes and any sticky adhesive left behind, but the process will be slow and painstaking.

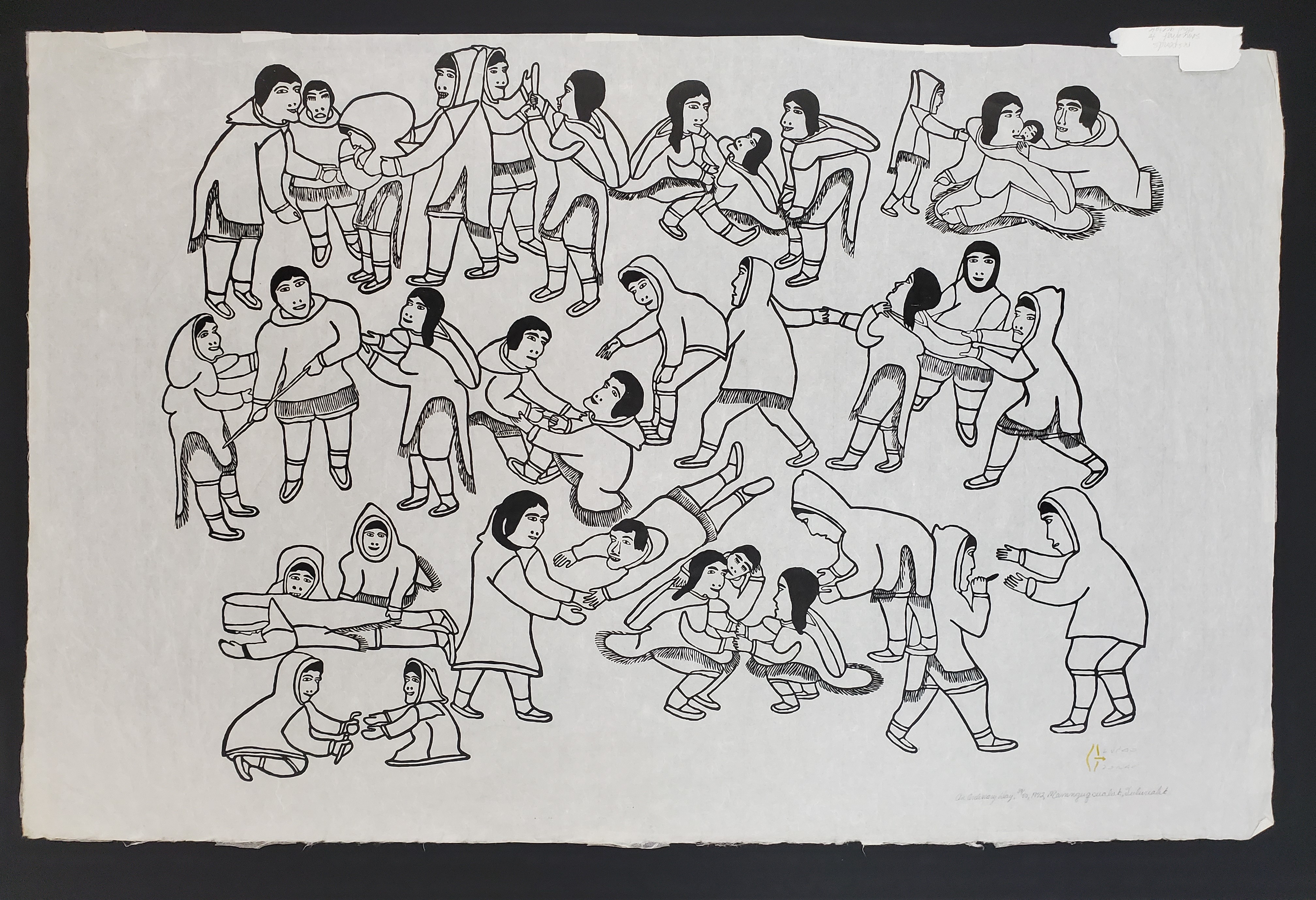

The project involves a recently donated stonecut print by Victoria Mamnguqsualuk with help from Ruth Annaqtuusi Tulurialik, both Inuit artists from the Qamani’tuaq (Baker Lake) community in Nunavut.

Victoria Mamnguqsualuk was most well-known for depicting Inuit legends and creation stories, which have traditionally been handed down through the generations via oral storytelling. In creating An Ordinary Day, she used her typical stylistic method of telling a story in what may appear to be a chaotic array of interactions among people: people playing, people arguing, people being married. According to her grand-daughter, artist Gayle Uyagaqi Kabloona, her style was directly influenced by her upbringing. Kabloona, in her article “How I Chose to Carry on My Family’s Artistic Legacy,” said:

"My gramma’s artwork tells a story, but not in the usual way that Western society is used to seeing chronological events. Mamnguqsualuk wasn’t raised in the school system, so the piece pays no attention to Euro-Westernism’s left-to-right reading convention."

Mamnguqsualuk’s stone cut prints relied on thin, translucent Japanese paper as a critical component to the printing process. Stone cuts are created completely by hand, not relying on the use of a printing press in the way traditional lithography on stone does. In stone cuts, the image is drawn onto the stone, and then all areas not to be printed are cut away, leaving the image in the raised areas of the stone. The raised image is then inked, sometimes with multiple colors used on various parts of the image. The thin paper is applied on top of the inked stone; the thin quality of the paper allows the printer to see the inked image underneath. The ink is then transferred onto the paper by gently pressing and rubbing the paper by hand with a flatted tool or disc along the raised areas. Once the ink has soaked into the paper, the print is pulled from the stone to dry.

An Ordinary Day arrived into my lab secured into a window mat. Removing a print from a window mat can be like renovating a Victorian house: when you start the work, you never know what you’ll find—so proceed with caution. In this case, tapes weren’t used to repair the print, they were used to secure the art into the mat. Lots of tapes. Around the entire perimeter of the print. Even parts of the print ended up being taped to the window mat.

I should clarify: the types of tape that were used weren’t what you’d use to wrap a gift. They were specialty “document repair tapes” that purport to be archival, and are sold even by vendors that I would typically view as reputable. Except ease is very popular, and apparently there is a large audience for these tapes. I’m appalled by one description of this product I just pulled off a vendor’s website: “Widely used by archivists, librarians in special collections, museum professionals as well as family historians to mend rips…” Holy smokes! Thankfully, APS staff are well-informed, and would never consider such a thing for any of our collection materials.

For those of you who may be curious, here’s a list of what not to buy to repair your documents and books, or secure your artwork into a window mat:

- self-adhesive linen tape

- anything that boasts a “pH neutral acrylic adhesive”

- transparent reinforcing book tape

- pressure-sensitive mending tissue

- J-Lar tape

- magic mending tape

- duct tape (yes, we’ve seen this)

- electrical tape (yup, this too)

- water-activated tapes that can only be removed with mineral spirits

- Filmoplast tape

- document repair tape

Of course, there are exceptions to every rule. Please consult a conservator if you want to use any of the above—we can tell you what to expect as the tape ages on the particular item you may want to use it on. We can’t, however, tell you how it may impact the market value of your taped item–that would be the purview of an appraiser.

And now for me, to begin to test potential tape removal systems. I’m sure I’ll find one that is just perfect for this wonderful print.