Managing Livingston Farrand’s Brittle Field Notebooks

It’s not very often that we think about making repairs designed to fail. But that’s exactly what I’m striving toward while working on multiple materials slated to be scanned and digitized.

Among these items are the field notebooks of anthropologist Livingston Farrand, in which he documented the language and folklore of the Quinault Indian Nation in 1897. These notebooks comprise a small fraction of the items within the American Council of Learned Societies Committee on Native American Languages collection that are being digitized for the Quinault Indian Nation’s Cultural Resources Department. The resulting digital files might also be included in the new Native Northwest Online project, a collaborative curation effort run through Washington State University that will reconnect Native communities with collections at non-Native repositories.

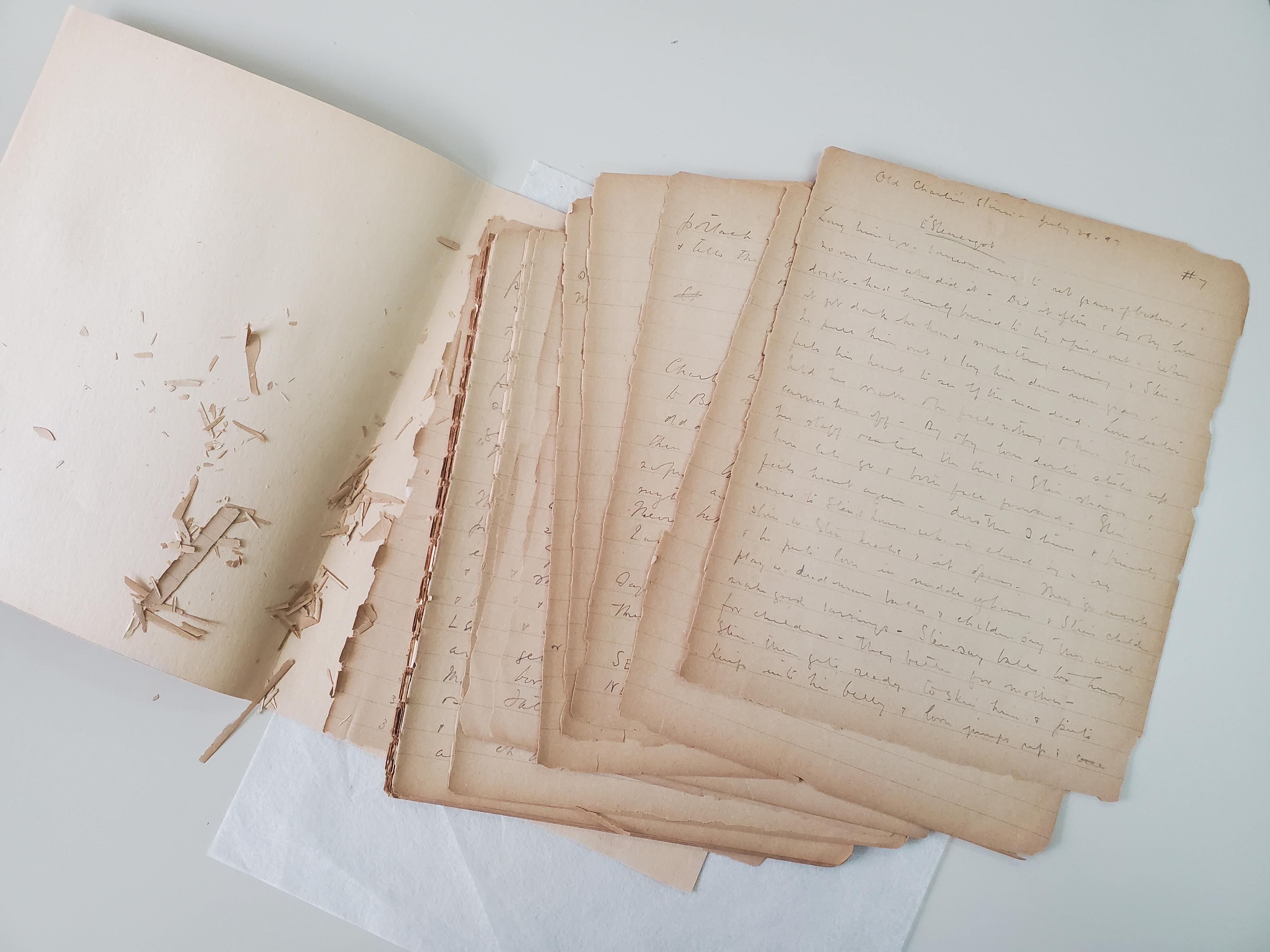

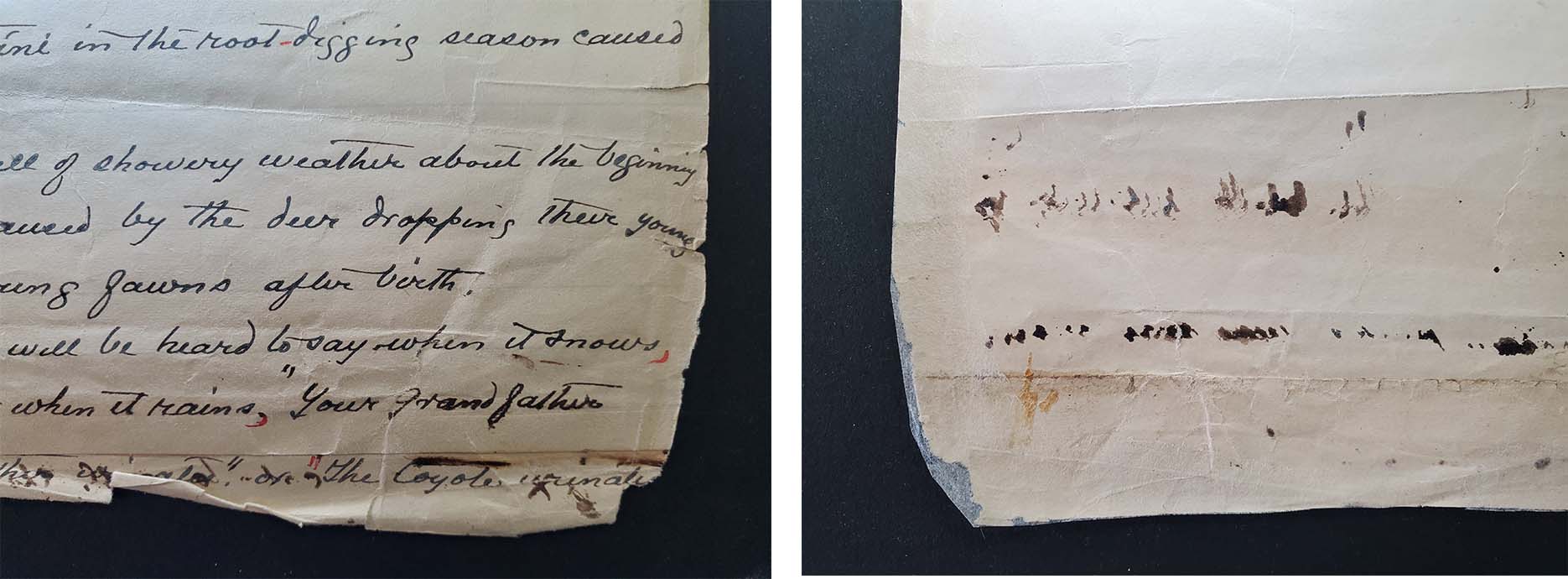

There are 15 Farrand notebooks in all, and the cause of their current condition is a bit of a mystery. Some of the notebooks are in excellent shape (see image above). Others have become so brittle over time that the covers and sewing are long gone, and within the housing are many tiny pieces of the pages that have broken off.

This curiosity, I have to admit, led me down a bit of a rabbit hole. Why are their conditions so different? Did Farrand source some ancient books he had laying about in his attic and then supplement them with hardier, brand-new volumes? Did he even have an attic? Because of these questions and others, I’m tempted to get into a mini biography on this fascinating historical figure, but I’ll urge you to look into his work more deeply on your own instead.

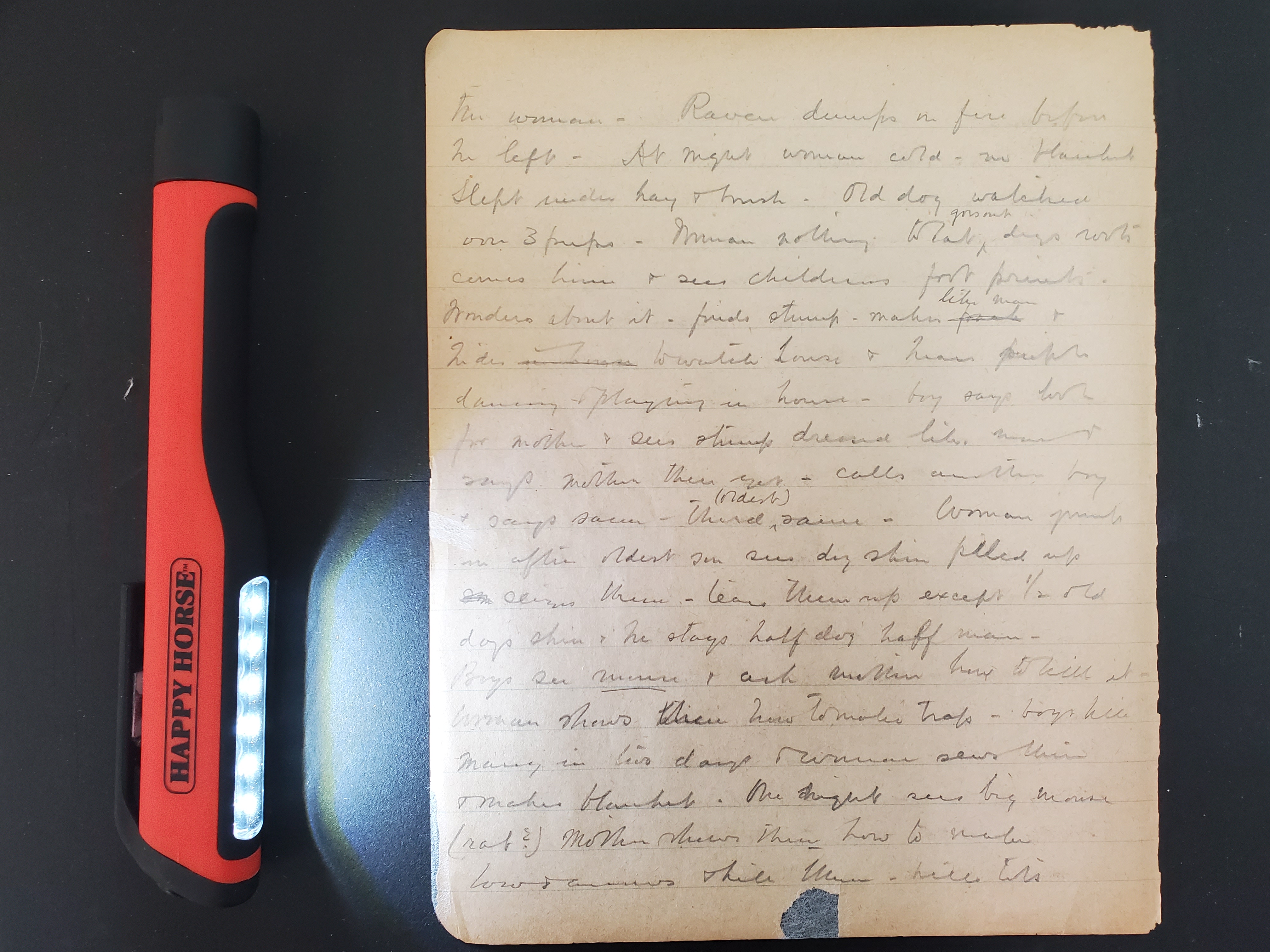

Getting back to brittle paper: especially disconcerting is that much of the text extends to the very edges of the notebook. Some of this text has already been lost because of the brittleness, and we want to prevent any future loss by mending edge tears and losses that are at risk of extending into the text’s body. To do this, the challenge is to apply a mend that gives just enough support to keep the pieces together, but, in the event of a slip, jostle, or other issue that may occur during research, staff use, or digitization, will ensure the mend gives way instead of the artifact. I’ve seen more than a few instances over the years where an artifact’s paper components tear beautifully, unintentionally, and directly alongside an Asian paper mend. These tears are the result of using mending paper that is stronger than the paper of the artifact itself, and the use of a strong, wet adhesive which forms a chemical bond with the artifact’s surface.

In a situation like the above, a traditional mending technique is used: a wet, tacky and strong paste is applied on thin, very strong strips of Asian paper. The paper itself is universally chosen for conservation due to the inherently long and chemically stable fibers from which they are made. Two of our favorite papers for this wet application of paste are Usu-Gami from Japan and Hanji 1201 from Korea. The pasted up strip of paper is applied to the artifact wet, covered with a piece of absorbent blotter, put under weight (we use scuba belt weights here at the APS), and left to dry for about 20 minutes. The result is a sturdy mend that is effectively incorporated into the artifact’s paper surface and can bend and flex along with the paper structure as needed. This technique is especially useful when mending pages of a book that need to be turned.

The mends that are best suited for these brittle papers, however, use a weaker type of paper, a different paste, and a different application method.

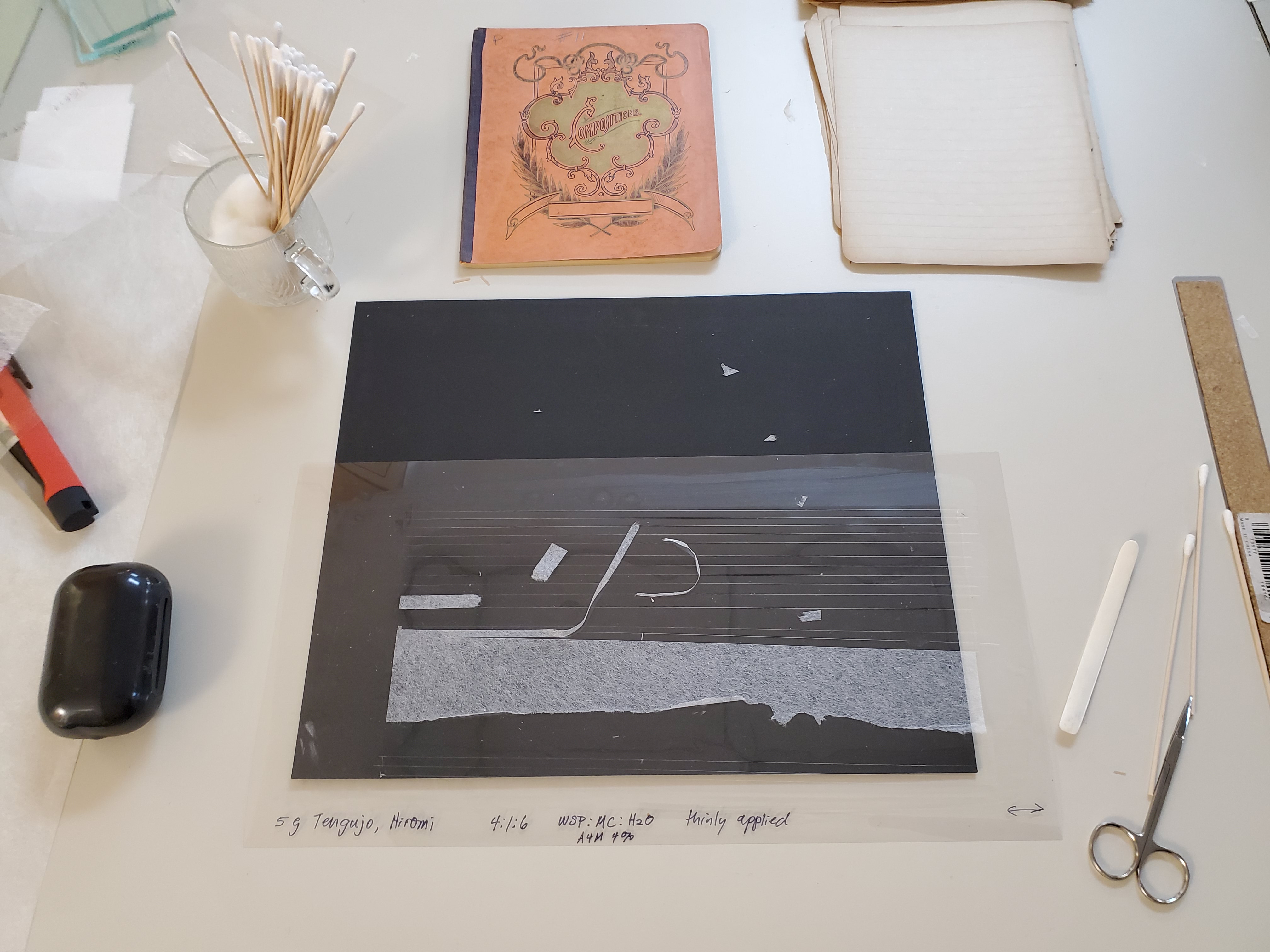

The mending paper that I’ve been using for this project is what we generically call “remoistenable tissue.” This tissue is made in the lab by hand by brushing a layer of water-soluble adhesive onto a sheet of clear polyester, laying the Asian paper of one’s choice on top, and allowing this to dry. Mending strips can then be cut while the paper is still attached to the polyester. The polyester allows the strips to release, transferring the adhesive from the polyester to the Asian paper. The strips are then dampened and applied to the torn paper. The advantages of using these strips are many: they are readily transportable and may be used in situations where one doesn’t have equipment to make paste or where the artifact cannot be exposed to too much moisture. Also, very little drying time is needed, making quick repairs possible.

I chose to make my remoistenable tissue from very light-weight Japanese paper. The thinnest paper I made is a variety of Tengujo, which weighs 3.5 grams per meter square. Also used were a 5-gram/meter squared Tengujo. The reason for using such thin paper is that thin paper tears more readily than heavier varieties. This is ideal when one hopes for the mend to be sacrificed if the artifact is put under any sort of stress that may lead to damage, which was especially important for these very brittle papers.

My adhesive mixture was a weak concoction of wheat starch paste watered down with methylcellulose, a gooey, viscous substance with only slight adhesive properties. The version I used (with a high viscosity of 4,000 centipoise) has a chemical structure that decreases penetration into porous materials–oh, like that brittle paper I’ve been talking about. Decreasing the penetration capabilities of an adhesive is a good thing when you want a weak mend.

Another advantage to using this method of mending is that I could apply just enough moisture (a soft spritz of deionized water from a cosmetic spray bottle) to just barely reactivate the adhesive. By doing this, I deliberately chose to create a weak bond between the artifact and the mending paper. These papers were never going to flex dramatically without breaking, but this weak bond further ensures that if the item is inadvertently banged about during handling, either the mending paper will tear or the adhesive will fail and the mend will release.

So, there you have it: weak mending paper, weak adhesive, weakly applied. Weak.