A Historian Walks into an Archive…

Header image: Anna Clemencia Guerrero, a PhD candidate in history and philosophy of science at Arizona State University and inaugural Jacques Barzun Fellow, examines botanical illustrations from the APS archives.

A historian walks into an archive–something they do all the time. But usually, historians do not enter archives to do the work of archivists. As the inaugural Jacques Barzun Fellow for Collections and Programming in the History of Biology, however, I learned how to think and work like an archivist, taking the unprocessed materials of 20th-century zoologist Emil Witschi and transforming them into an organized collection for future historians of biology (like me) to use. To be entirely honest, I had never worked in any archive, in any capacity, before coming to the American Philosophical Society’s Library & Museum in January 2022. I did not know what to expect—of Witschi’s materials, of the work it would take to process them, of anything. Now, at the end of my training, I will highlight three of the most surprising artifacts I encountered and share the most important lessons these items taught me.

Drawing Connections

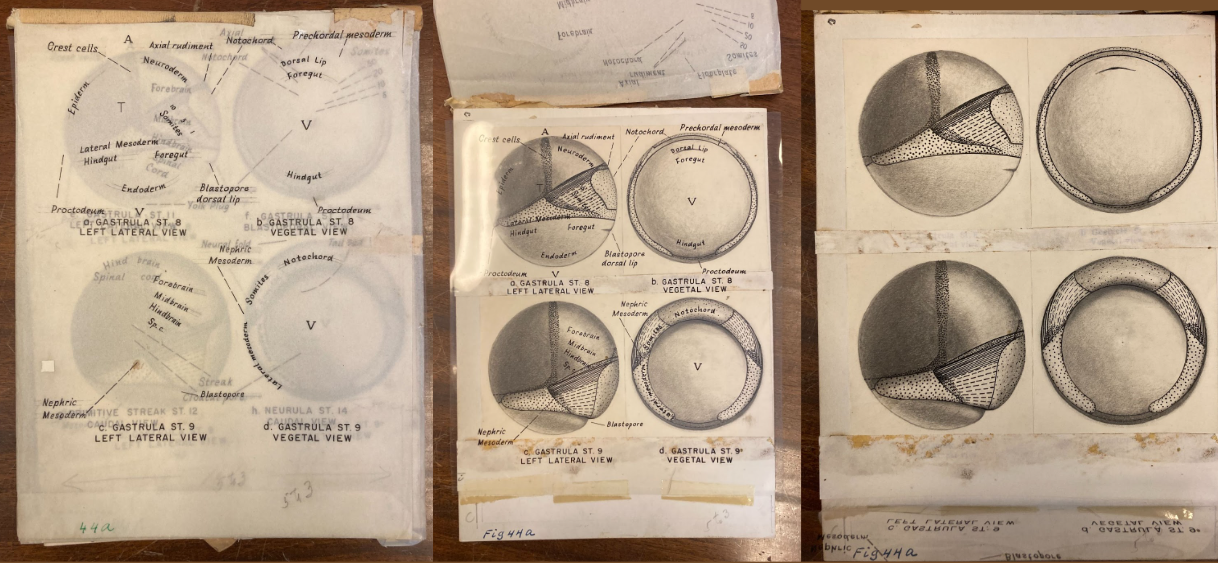

Born in Switzerland, Emil Witschi moved to the United States in the 1920s to conduct zoological research about sexual differentiation and the development of vertebrates at the University of Iowa. After producing close to 200 scholarly works and training at least 40 students during his career, Witschi was asked to author an embryology textbook called Development of Vertebrates. This textbook, a copy of which is included in his Papers, contains an abundance of illustrations. Witschi himself was a talented visual artist. This skill would have been important for his research, since much of it involved watching and drawing animals, their tissues, and their cells as they changed shape during development. Much to my delight (especially as a scientific illustrator and historian of biological images), the collection included four boxes full of figure preparations for Witschi’s textbook. While it is not clear if Witschi did any of these drawings himself, it was incredible to see the artists’ processes and compare these drafts to the final images that appear in the textbook.

As a historian of biology, I have experience in studying textbooks as historical artifacts. Finding the figure preparations reminded me that the information and images in science textbooks are the result of decisions made by scientists, artists, editors, and publishing companies. For historians, biology textbooks do not represent a set of facts. Instead, they represent a set of choices. In order to understand where information in a particular textbook comes from, and why it is there at all, historians must go beyond studying the textbook itself. Figure preparations can be invaluable tools for understanding the specific decisions people made, why those decisions were made at all, and can also help explain how modern-day science developed. These are exactly the kinds of tidbits that might exist in an archive.

Birds of a Feather Get Processed Together

Witschi’s collection, somewhat unsurprisingly, contains a lot of data recorded on paper: tables of hormone measurements, illustrations and photographs of organisms, and diagrams of ideas and theories. This data is related to experiments performed on a variety of organisms, from rats and mice, to frogs, to many species of birds. On a chilly day just a few weeks into my fellowship, I was going through a box of unorganized paper materials seemingly like any other. I was just starting to feel a little more confident in my archival skills as I picked up another folder. Suddenly, the table and I were covered in feathers! Data, still, but of a different sort. Stunned, I gathered those loose feathers from my lap, the table, the floor, and from more folders, wondering how long they had been stored this way. I am pleased to report that these artifacts are now neatly contained in envelopes for the next interested researcher.

When historians read the work of a modern-day biologist, they are almost always reading a publication, sometimes on paper, but more often on a computer. Reading data this way removes most of the substance of biological research, a scientific field that considers itself concerned with the physical world. Historians may primarily work with papers, but these neat packages represent hours of experimentation with living organisms, dangerous chemicals, and the frequent failure that accompanies such complex work. Witschi’s feathers, and the circumstances in which I found them, frequently remind me to be thoughtful about the materiality of historical biological research.

Writing a Sensational Story

Sometimes, the press communicates with the public about a scientist’s research. The Witschi Papers contain a thick folder of newspaper articles and clippings that span the 1950s and 60s, from both local and national news sources, about his various experiments and their implications for the broader world. It is unsurprising that news sources would sensationalize experiments related to predicting a future child’s sex or changing an organism’s sexual characteristics (frogs and rats, in Witschi’s experiments), as many people rely on categories related to sex and gender to make sense of themselves and the world. More surprising than the news stories themselves were the letters that followed. People from all over the United States wrote to Witschi in response to these sensational stories. Some women asked for advice on how to predict or influence the sex of their next child. Some men wrote to say that they had always wished to be the opposite sex, and to ask Witschi if there were ways to accomplish such a change in people. I expected to be intellectually stimulated by the Witschi collection, but I did not expect to be so emotionally impacted by the response to his work.

Historians help make sense of the past by writing stories. But making sense of the past should not just be for historians, nor for the benefit of our historical narrative’s subjects. The stories that historians of science write should benefit those who do not have access to archives—those who do not have the time, the know-how, or privilege to comb through them. Those letters from the public remind me that the kind of work professional researchers like scientists and historians publish, and how that work is framed, will influence how people understand themselves and the world. The work that archivists do, locating and choosing which materials in a collection are marked as significant, partially shapes the stories that historians can tell. My time doing the work of an archivist taught me that although the day-to-day operations of an archive might often feel slow and quiet and small, the work of archivists, librarians, and historians in conjunction is potentially high stakes, such that we have a responsibility to learn from and with each other to tell better stories.