First Do No Harm: Restoring Hippocrates’ Aphorisms

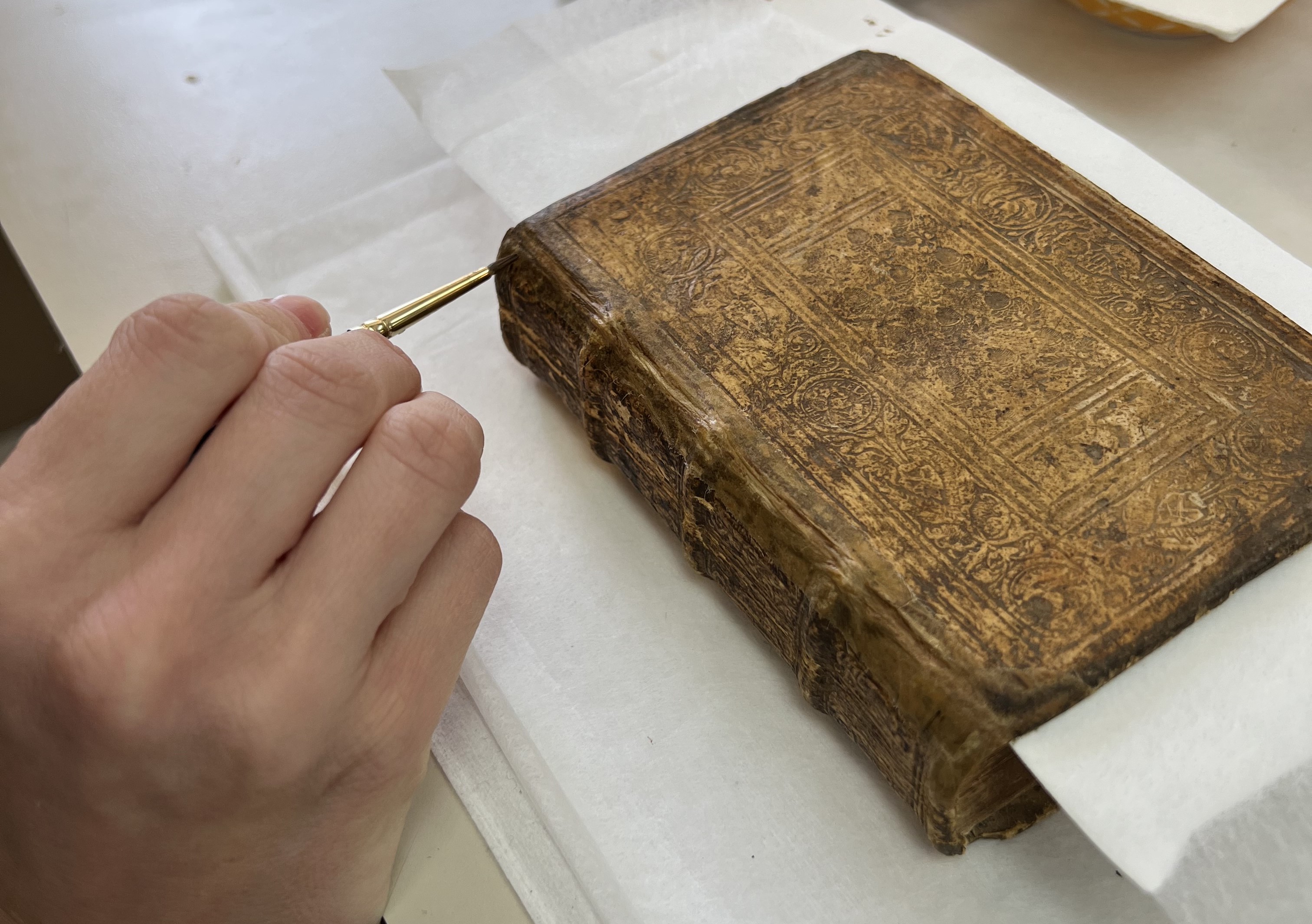

Header Image: 2023 Willman Spawn Conservation Intern Charlotte “Charly” Starnes puts the finishing touches on her treatment of a 1549 French copy of Aphorismi Hippocratis Graece et Latine.

This summer I had the pleasure of supervising Willman Spawn Conservation Intern Charlotte Starnes, a Library and Archives Conservation Education Fellow in the Garman Art Conservation Department at SUNY Buffalo State. She joined the American Philosophical Society in July, after spending two weeks soaking up book history at London Rare Books School and a month studying bookbinding with fine binder Don Rash. When she arrived, I presented her with a selection of books that required repair: 20th-century trade bindings with split text blocks, warped boards, or torn spines; a 19th century manuscript documenting the weather; and a 1552 German-style binding with a detached front cover and several loose leaves. To my delight, Charlotte (or “Charly”) selected the two most complicated treatments for her four-week internship, including the latter.

The Society’s copy of Aphorismi Hippocratis Graece et Latine, or Hippocrates’ Aphorisms in Greek and Latin, was printed in Lyon, France, in 1549 and bound in alum-tawed, blind-tooled pigskin in the German fashion three years later. Latin and Greek marginalia in iron gall ink throughout the volume indicate that its former owners consulted the book regularly and commented on its contents. An inscription on the title page also reveals that the book once belonged to “J.R. Coxe, MD” (John Redman Coxe, 1773-1864), who was a prominent physician and a former APS Member.

The book contains the sayings of Hippocrates (ca. 460-370 BCE), a Greek physician who professionalized the field of medicine during the Classical period. While it is now difficult to know which ancient medical writings can be traced directly to Hippocrates, he was one of the first doctors to relate illness not to divine displeasure or bad luck, but to its sufferer’s environment, diet, and way of life. He is also credited with developing the Hippocratic Oath, in which physicians swear to “do no harm” to their patients. The Society’s 16th-century translation of Hippocrates’ aphorisms includes his ideas about the treatment of illness as well as commentary by Galen (129-ca. 216 CE), a later Greek physician, writer, and philosopher whose ideas dominated Western medicine from the Middle Ages into the 17th century.

Like physicians, conservators refrain from harming their inanimate “patients” whenever possible, and they often choose the treatment protocol that requires the least change to an artifact’s original construction. In books with detached boards and leaves, like the Society’s copy of Hippocrates’ Aphorisms, conservators have multiple options for repair, from disbinding and re-sewing the book entirely to more restrained, local forms of reinforcement. With my guidance, Charly chose to mend and reattach the detached loose leaves of the book by sewing them over new strips of ramie ribbon.

The strips were inserted beneath the tawed-skin on the spine and adhered in place with wheat starch paste, an adhesive that is readily reversible with moisture. The pieces of ribbon were then twisted into bow-tie shapes to provide narrow places over which the sewing thread could pass. The wider second half of each bow-tie was then secured beneath the lifted skin over the front board. Charly then mended over the gap between the spine and the front board with Asian paper, and painted the paper with acrylic paints to match the tooling of the original binding—an exercise in which she showed an exquisite sense of color, a fine eye for detail, and enviable hand skills.