Ali in the Archive

In a recent program, “Ali in the Archive,” I took a journey into the American Philosophical Society’s archive to see material related to two scientists: Chien-Shiung Wu and Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin. In the program, we explored how to do research in the library, learned about the history of both scientists, and, finally, detailed detailed discoveries from my archival digging. This blog post will be an abbreviated version of this program, specifically spotlighting Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin.

Our first stop is the APS website. If you are a researcher, you’ll need to make an appointment first. All visitors (and staff) must request an appointment in the Reading Room by emailing [email protected]. Researchers must also register for an AEON account —a one-stop-shop for calling items and seeing both their availability and other general information about them. Upon arrival, researchers will be asked to complete their registration, providing their name, current address, institutional affiliation (if any), and two forms of identification—at least one with a photograph.

But first, some background. X-ray crystallographer Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin, was born on May 12, 1910, and grew up with a family that supported and encouraged her interests in science. As a child she was always interested in crystals and their structure. When Hodgkin received her Ph.D. in chemistry, she specialized in x-ray crystallography. Not sure what that is? It’s when you shine x-rays through crystals in order to figure out their atomic structures. After taking photographs of the crystal, you then use a lot of complicated math to reverse engineer what this crystal’s makeup looks like, which cannot be seen by the naked eye. Once you know the structure of something, you understand it better, meaning you could manufacture it on a large scale. Hodgkin would go on to figure out (with the help of her graduate students) the structures of penicillin, vitamin B12, and insulin. She would also win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry “for her determination by X-ray techniques of the structure of important biochemical substances.”

What did I find about Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin in the APS archives? One thing to note about archives is that we don’t have everyone’s collections. Hodgkin worked at Oxford University for most of her life, so a large part of her papers and correspondences are in The Bodleian Libraries, Oxford. So in this case, we have to find her stories in other collections we have more immediate access to. For example, I found Hodgkin in a couple of APS collections: the Horace Freeland Judson Collection, the Jenny Pickworth Glusker Papers, and the A. Lindo Patterson Papers. The Judson Collection contained transcripts from an oral history with Hodgkin, talking about her scientific work. You can see the edited marks on the manuscript below as he was typing up the oral history in 1971.

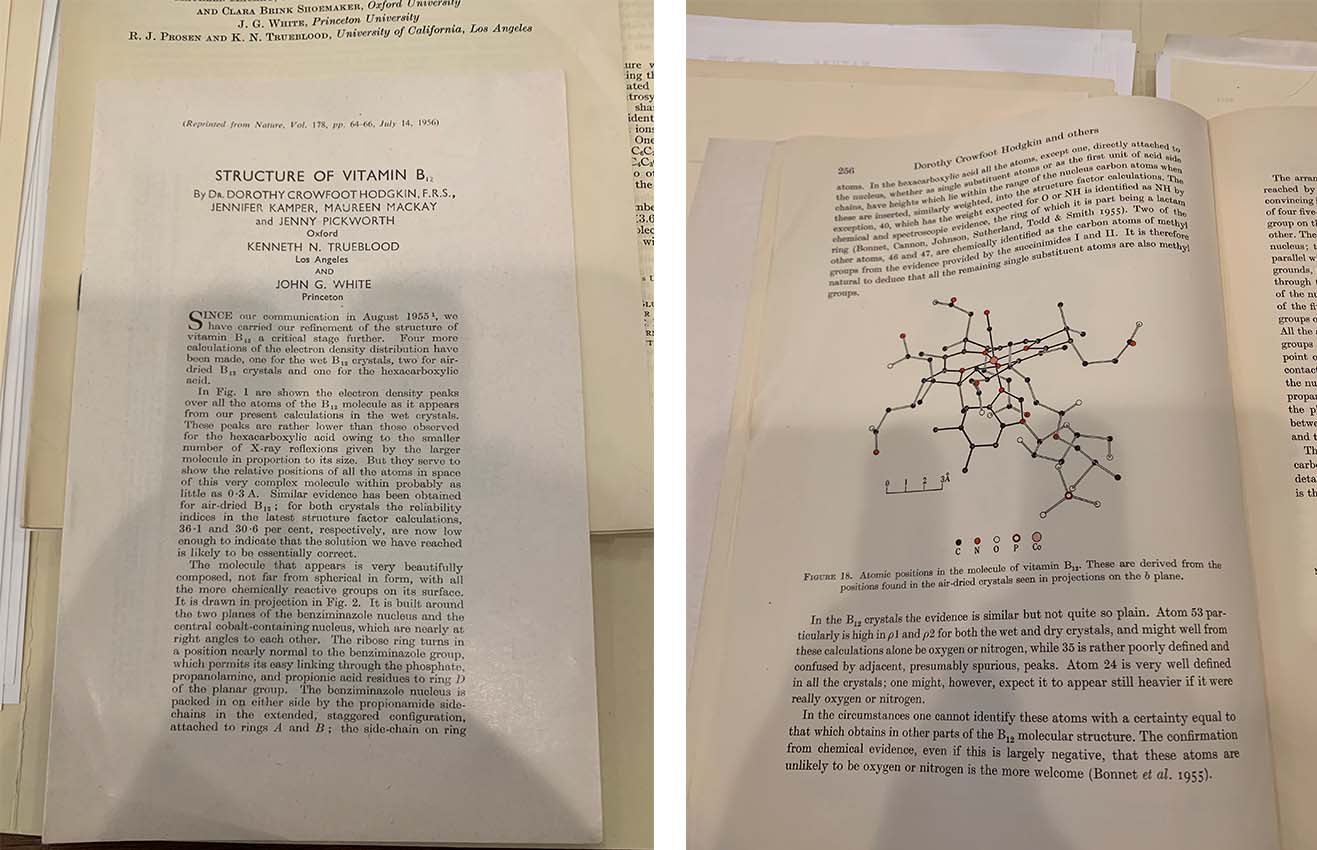

In the Jenny Pickworth Glusker Papers, Glusker did her graduate work with Dorothy Hodgkin and helped contribute to figuring out the structure of vitamin B12. If you are very interested in the science behind their work, then this is the collection to look at. Below you will see a reprinted article centered on their vitamin B12 research. Listed among its authors are: Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin and Jenny Pickworth, and others. You also see another section that shows vitamin B12’s atomic structure.

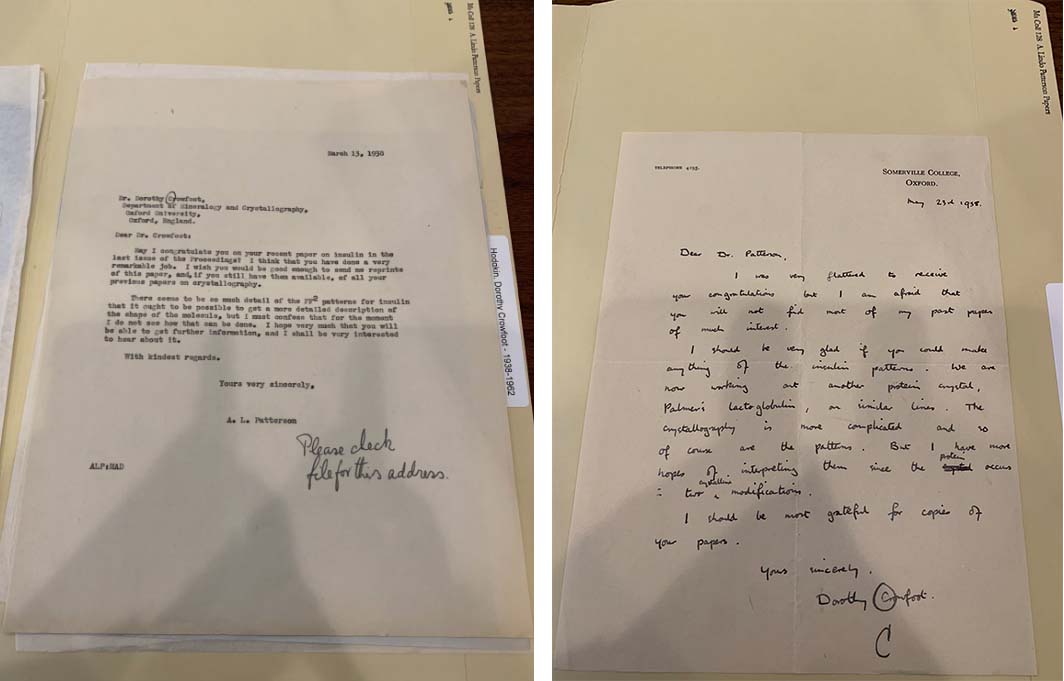

Finally, in the A. Lindo Patterson Papers is correspondence from the 1930s-1960s. Patterson created a mathematical function that helps figure out three dimensional structures in x-ray crystallography. In the 1938 letter below to the left, Patterson, writes to Dr. Crowfoot (very formal at this point), “May I congratulate you on your recent paper on insulin in the last issue of the Proceedings? I think that you have done a very remarkable job. I wish you would be good enough to send me reprints of this paper, and, if you still have them available, of all your previous papers on crystallography.” This is in 1938. Hodgkin didn't figure out the structure of insulin until 1969. This important work spanned decades. Here we see both support between colleagues and the exchange of scientific knowledge. Hodgkin later responds back to Lindo that she was “...flattered to receive your congratulations but am afraid that you will not find most of my past papers of much interest.” What we see in these correspondences is a friendship as well.

(Right) Dorothy Crowfoot to A. Lindo Patterson, May 23, 1938. APS.

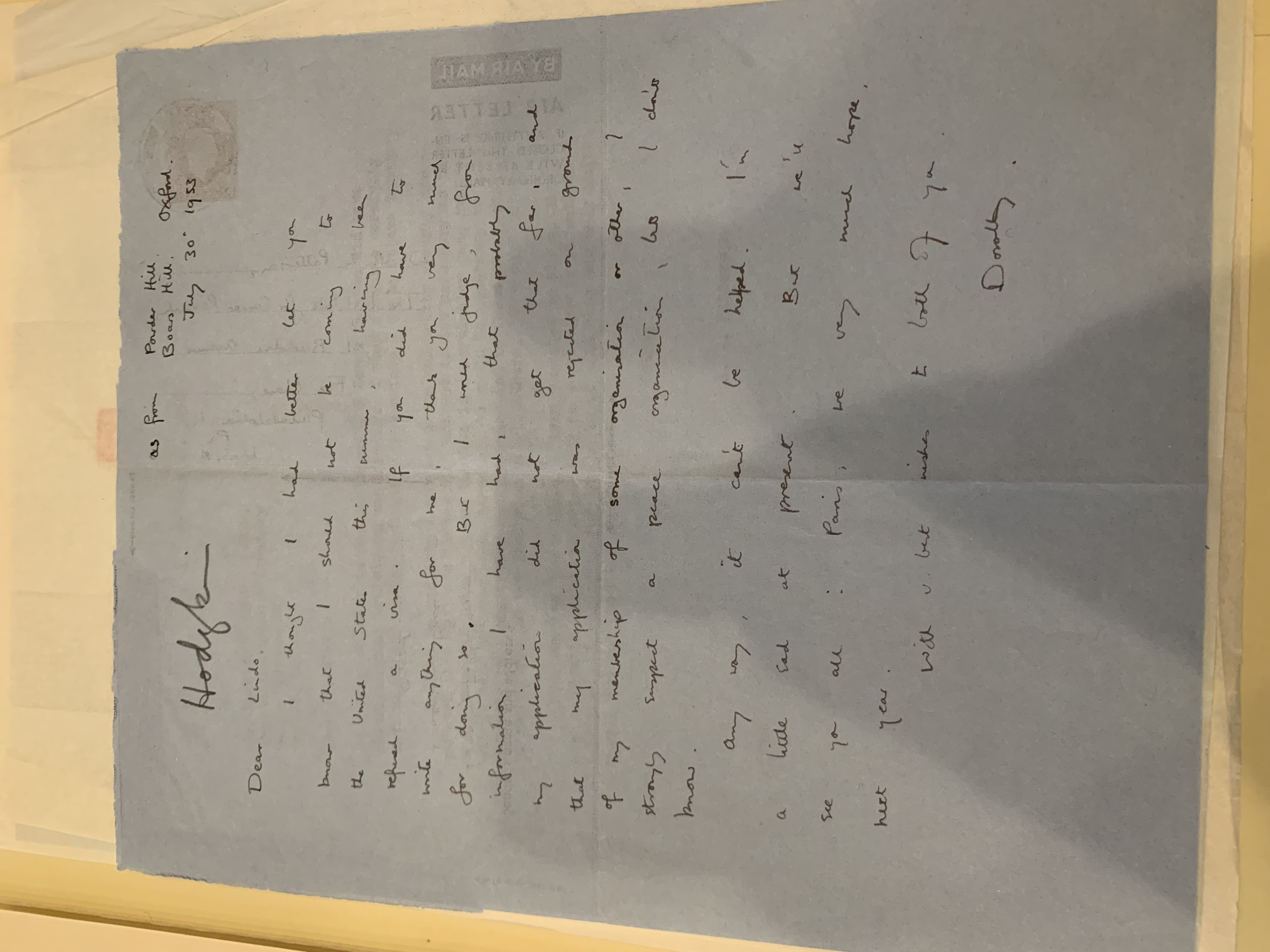

At one point in 1953, Hodgkin asked Patterson if she could name him as a reference in order to obtain a visa to visit the U.S. for a conference. She was quite excited to go to this conference, held by chemist Linus Pauling, and even mentions how she hopes (if she’s accepted) to see the Grand Canyon as well during her time in the U.S. Unfortunately, by July 30, 1953 (in the letter to the left below), she relates to Patterson that her application was rejected. She says at one point, “But I would judge from information I have had, that probably my application did not get that far and that my application was rejected on grounds of my membership of some organization or other, I strongly suspect a peace organization, tho I don’t know.” Hodgkin was a member of several peace organizations throughout her life, and even helped form the International Union of Crystallography. These organizations accepted people from all over, even from Communist nations. This did not sit well with a very anti-communist U.S. government. In another letter from Patterson, he mentions no one ever contacted him for a reference, so it seems that her visa never even had a chance.

Hodgkin was always committed to the idea of world peace and the exchange of scientific knowledge. Instead of going to the U.S. she was invited to Moscow, which she said “was very interesting, very amusing, and sometimes a very moving experience.” There is a silver lining though, Hodgkin would later be able to go to the U.S. in 1960. One letter I found had her talking about a possible visit in November of that year. She even throws around a title for a lecture she could present. It seems the visit went well since, in another letter to her, Patterson, ended with the closing sentence, “Betty and I still remember fondly your visit here and hope you will both come again very soon.”

With this journey through the APS archives with Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin, I hope I’ve showed you some of the stories you can discover in the archive.