|

| Title page of Bartram's Travels |

William (1739-1823), the fifth son of the botanist,

John Bartram, followed his father into the field, both literally and figuratively. Even while receiving the rigorous formal education that his father desired but lacked, William's heart was set on the study of nature. By his mid 20s, he was his father's regular companion forays into the hinterland to collect plants and animals for their European clientele, and his artistic talent and scientific training made him invaluable as a visual interpreter of nature.

In 1761, William shucked an apprenticeship in Philadelphia to join his uncle William in business on the Cape Fear River, North Carolina. Although failing to thrive as a merchant - in his father's words "Everything goes wrong with him there" -- William was perfectly situated to assist when his father undertook an ambitious scientific tour of East Florida in 1765-1766. The experience was beneficial for William in several ways, most importantly in attracting the support of the English Quaker scientist, John Fothergill, who offered William £50 per annum, plus bonuses, to collect unusual specimens. With patronage in place, Bartram set out in April, 1773, on his own four year odyssey across the southeast, wandering wherever opportunity and inclination combined.

Bartram was omnivorous in his scientific interests, collecting information as he traveled the byways between Savannah and Charleston on everything from botany to birds, and coal to climate. His artistic skills were put to good use, making hundreds of sketches of birds, plants, and animals, but it is his prose that makes the Travels memorable. Although he apparently did not set out with publication in mind, his father had urged William to keep a careful journal of events, if for no other reason than as a scientific record, and with the continued encouragement of his friends, this became the basis for a book in 1791. William's high-toned education prepared him well for the task, his distinctive literary style pairing exacting scientific observation with florid prose. The Travels is characterized by romantic flights effusing over the glories of nature, and abundant asides, in which Bartram sketches a vision of the world in which all life is bound by emotion and mind.

|

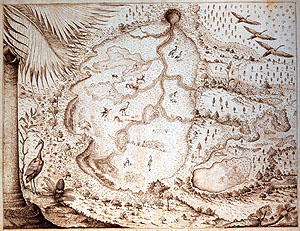

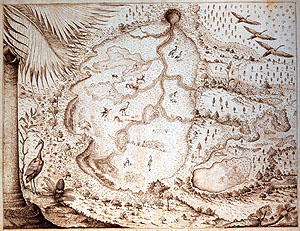

| Bartram's sketch of the Great Alachua Swamp, 1765 |

It was now after noon; I approached a charming vale, amidst sublimely high forests, awful shades! darkness gathers around, far distant thunder rolls over the trembling hills; the black clouds with august majesty and power, moves slowly forwards, shading regions of towering hills, and threatening all the destructions of a thunderstorm; all around is now still as death, not a whisper is heard, but a total inactivity and silence seems to pervade the earth; the birds afraid to utter a chirrup, and in low tremulous voices take leave of each other, seeking covert and safety; every insect is silenced, and nothing heard but the roaring of the approaching hurricane; the mighty cloud now expands its sable wings, extending from North to South, and is driven irresistibly on by the tumultuous winds, spreading his livid wings around the gloomy concave, armed with terrors of thunder and fiery shafts of lightning; now the lofty forests bend low beneath its fury, their limbs and wavy boughs are tossed about and catch hold of each other; the mountains tremble and seem to reel about, and the ancient hills to be shaken to their foundations: the furious storm sweeps along, smoaking through the vale and over the resounding hills; the face of the earth is obscured by the deluge descending from the firmament, and I am deafened by the din of thunder; the tempestuous scene damps my spirits, and my horse sinks under me at the tremendous peals, as I hasten for the plain.

|

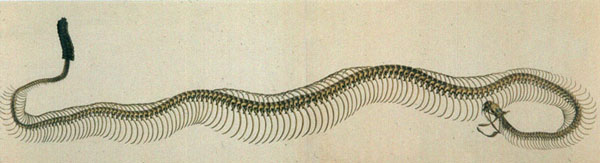

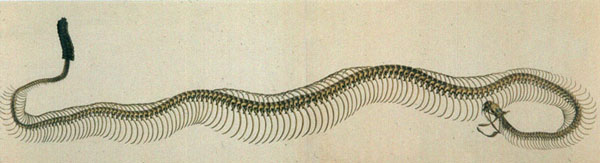

| Sketch of a rattlesnake skeleton, by Benjamin Smith Barton |

Like his father, William was no orthodox Quaker, but a Quakerly spirituality pervades his writing and shaped his observations. In describing the rattlesnake, an object of particular fascination for European naturalists, Bartram delivered the

de rigueur catalogue of rattles, venom, and fangs, but added a distinctive twist with regard to the snake he called a "generous, I may say magnanimous creature."

Since, within the circle of my acquaintance, I am known to be an advocate or vindicator of the benevolent and peaceable disposition of animal creation in general, not only towards mankind, whom they seem to venerate, but also towards one another, except where hunger or the rational and necessary provocations of the sensual appetite interfere, I shall mention a few instances, amongst many, which I have had an opportunity of remarking during my travels, particularly with regard to the animal I have been treating of. I shall strictly confine myself to facts.

When on the sea coast of Georgia, I consented, with a few friends, to make a party of amusement at fishing and fowling on Sapello, one of the sea coast islands. We accordingly descended the Alatamaha, crossed the sound and landed on the North end of the island, near the inlet, fixing our encampment at a pleasant situation, under the shade of a grove of Live Oaks and Laurels on the high banks of a creek which we ascended, winding through a salt marsh, which had its source from a swamp and savanna in the island: our situation elevated and open, commanded a comprehensive landscape; the great ocean, the foaming surf breaking on the sandy beach, the snowy breakers on the bar, the endless chain of islands, checkered sound and high continent all appearing before us. The diverting toils of the day were not fruitless, affording us opportunities of furnishing ourselves plentifully with a variety of game, fish and oysters for our supper. About two hundred yards from bur camp was a cool spring, amidst a grove of the odoriferous Myrica: the winding path to this salubrious fountain led through a grassy savanna. I visited the spring several times in the night, but little did I know, or any of my careless drowsy companions,. that every time we visited the fountain we were in imminent danger, as I am going to relate. Early in the morning, excited by unconquerable thirst, I arose and went to the spring; and having, thoughtless of harm or danger, nearly half past the dewy vale, along the serpentine foot path, my hasty steps were suddenly stopped by the sight of a hideous serpent, the formidable rattle snake, in a high spiral coil, forming a circular mound half the height of my knees, within six inches of the narrow path. As soon as I recovered my senses and strength from so sudden a surprise, I started back out of his reach, where I stood to view him: he lay quiet whilst I surveyed him, appearing no way surprised or disturbed, but kept his half-shut eyes fixed on me. My imagination and spirits were in a tumult, almost equally divided betwixt Thanksgiving to the supreme Creator and preserver, and the dignified nature of the generous though terrible creature, who had suffered us all to pass many times by him during the night, without injuring us in the lease, although we must have touched him, or our steps guided therefrom by a supreme guardian spirit. I hastened back to acquaint my associates, but with a determination to protect the life of th generous serpent. I presently brought my companions to the place, who were, beyond expression, surprised and terrified at the sight of the animal, and in a moment acknowledged their escape from destruction to be miraculous; and I am proud to assert, that all of us, except one person, agreed to let him lie undisturbed, and that that person at length was prevailed upon to suffer him to escape.

|

Mico Chlucco, the Long Warrior, or King of the Seminoles

(click to see Bartram's original sketch of Mico Chlucco,

Creek Chief) |

As it did for many of his peers, the study of Indians fell logically under the head of natural history for Bartram, and his

Travels includes lengthy, first-hand accounts of the Cherokee, Creek, and Choctaw Indians, including valuable demographic, political, religious, and cultural information.

A debilitating illness leading to partial blindness caused Bartram to cut his journey short, and he returned to Philadelphia in 1777. After his momentous southeastern tour and the death of his father in September, William settled in Kingsessing and entered into partnership in the botanical supply business with his brother, John. Like his father, William was a nurturer of American science, earning election to the Academy of Natural Science of Philadelphia in its first year of existence (1812) and assisting a number of younger naturalists in establishing themselves, including his own great-nephew, Thomas Say, and the great orthnithologist, Alexander Wilson. William died at Kingsessing in 1823.