Of Myths and Bones:

Early Modern Conceptions of Animals Case Two

Early modern European naturalists relied upon third-person accounts of animals, referring to texts rather than observation to inspire their depictions of animals. They utilized ancient and contemporary sources alike. Early modern works contain mythical beasts alongside real animals; the fantastic is intermingled with the realistic.

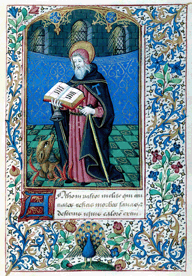

Dating from circa 1475, the colorful depiction of Saint Anthony Abbot is from a medieval book of hours. A third- and fourth-century hermit who eventually abandoned civilization to live in the Egyptian desert, Anthony was a skilled healer of both humans and animals. For a time, Anthony was a pig herder. He is depicted in this image as preaching to a porcine creature. Saint Anthony is still celebrated in Catholic countries today. His feast day is celebrated with animal blessings.

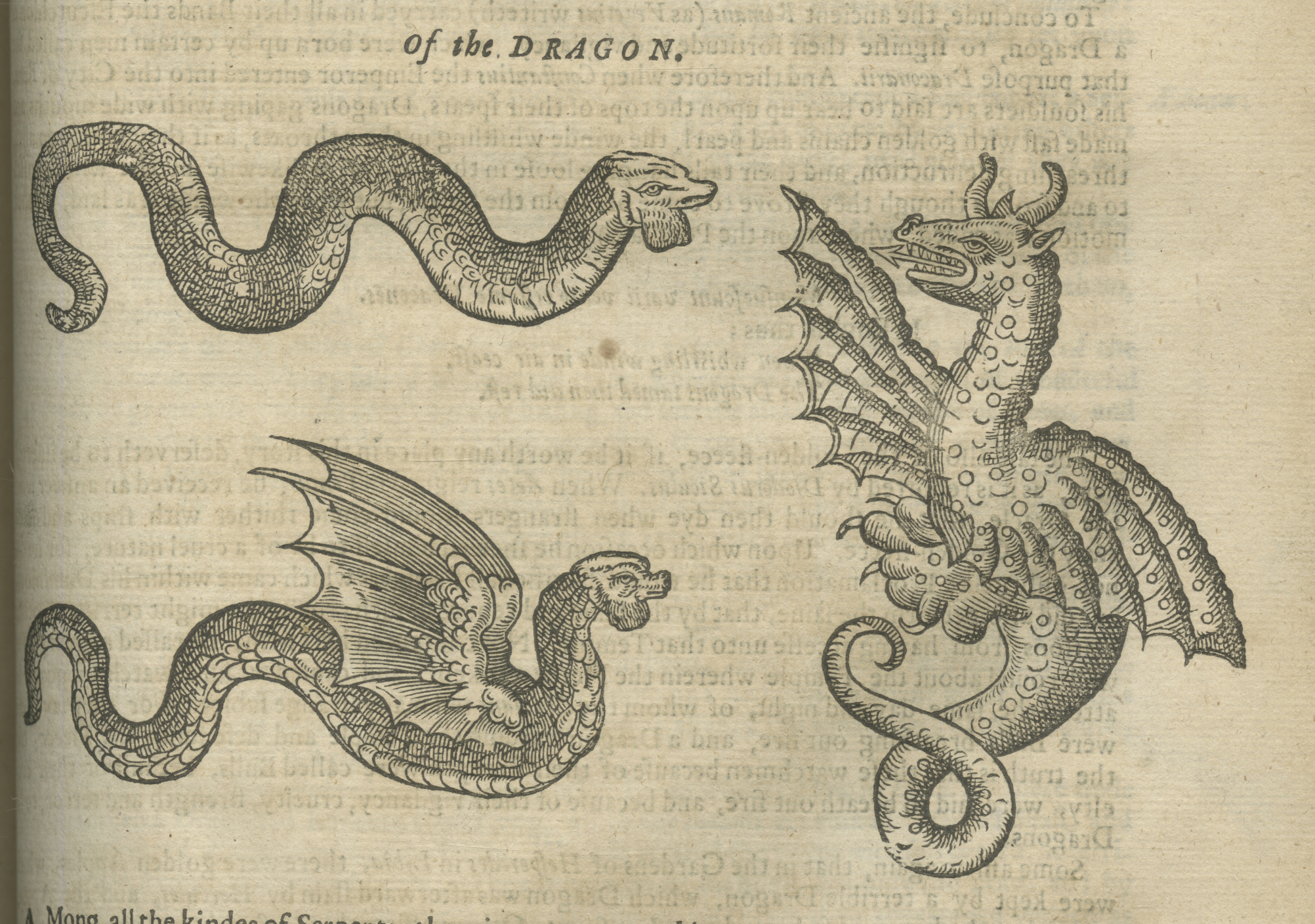

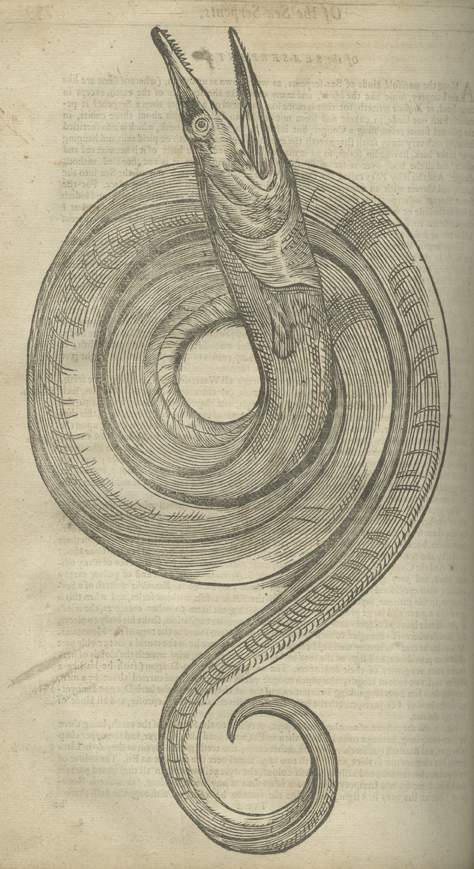

From faith to fantasy, English clergyman Edward Topsell created the 1100-page work, History of the Four-Footed Beasts and Serpents in 1607-1608. APS possesses a reissue dated 1658. Topsell's work borrows heavily from the work of early Swiss naturalist Conrad Gesner, and contains quotations from scripture and ancient mythology, physicians and poets. Topsell defends this approach by stating, "Lest it should seem incredible, as the foolish world is apt to believe no more than they see, I have [added] the testimonies of sundry learned men." Classical scholars have just as much importance as contemporary scientists. Mythical beasts appear next to real animals. Yet, even mythical beasts have dietary concerns. Dragons, according to Topsell, seek out lettuce to ease indigestion, but avoid apples like the plague. Apples give them terrible gas! This page includes Topsell's dragons, winged dragons, sepedons, and sea serpents.

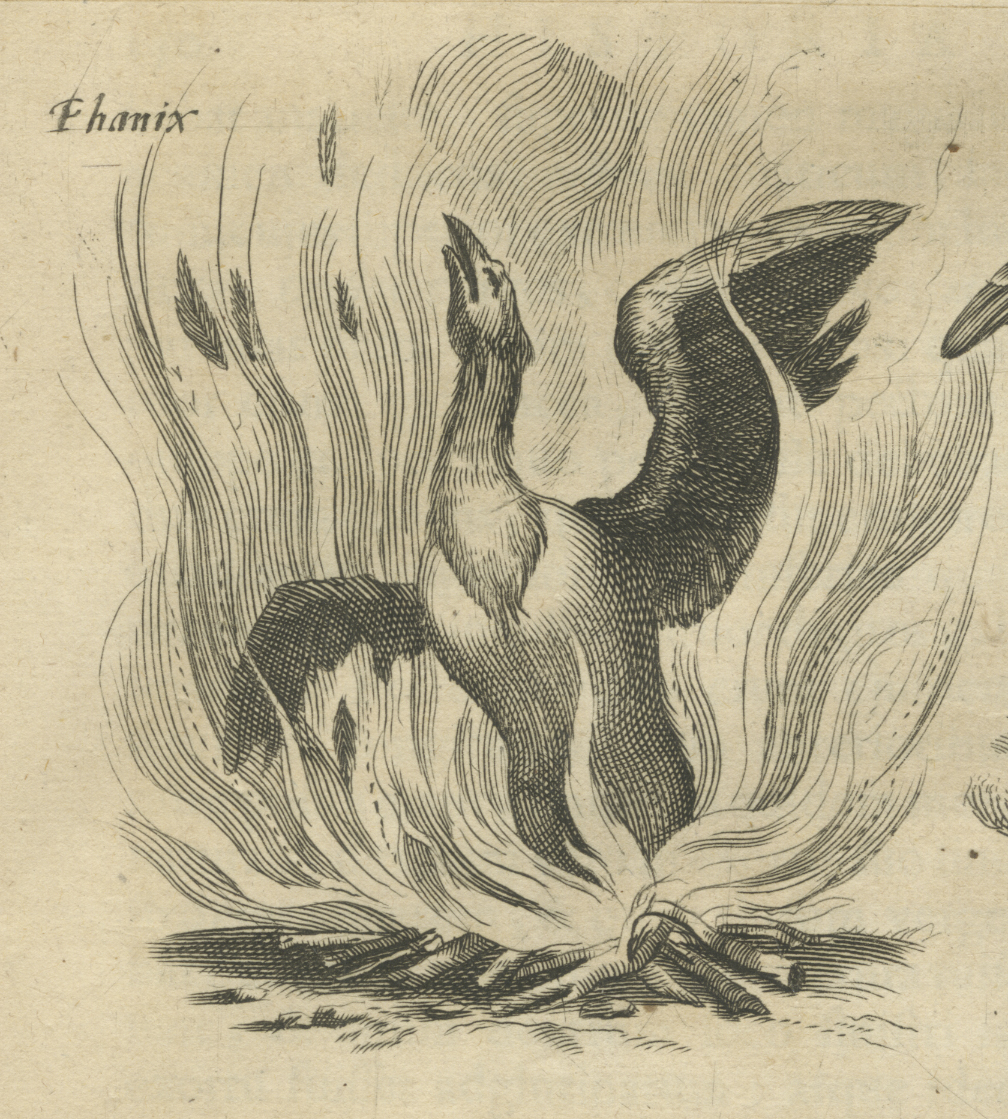

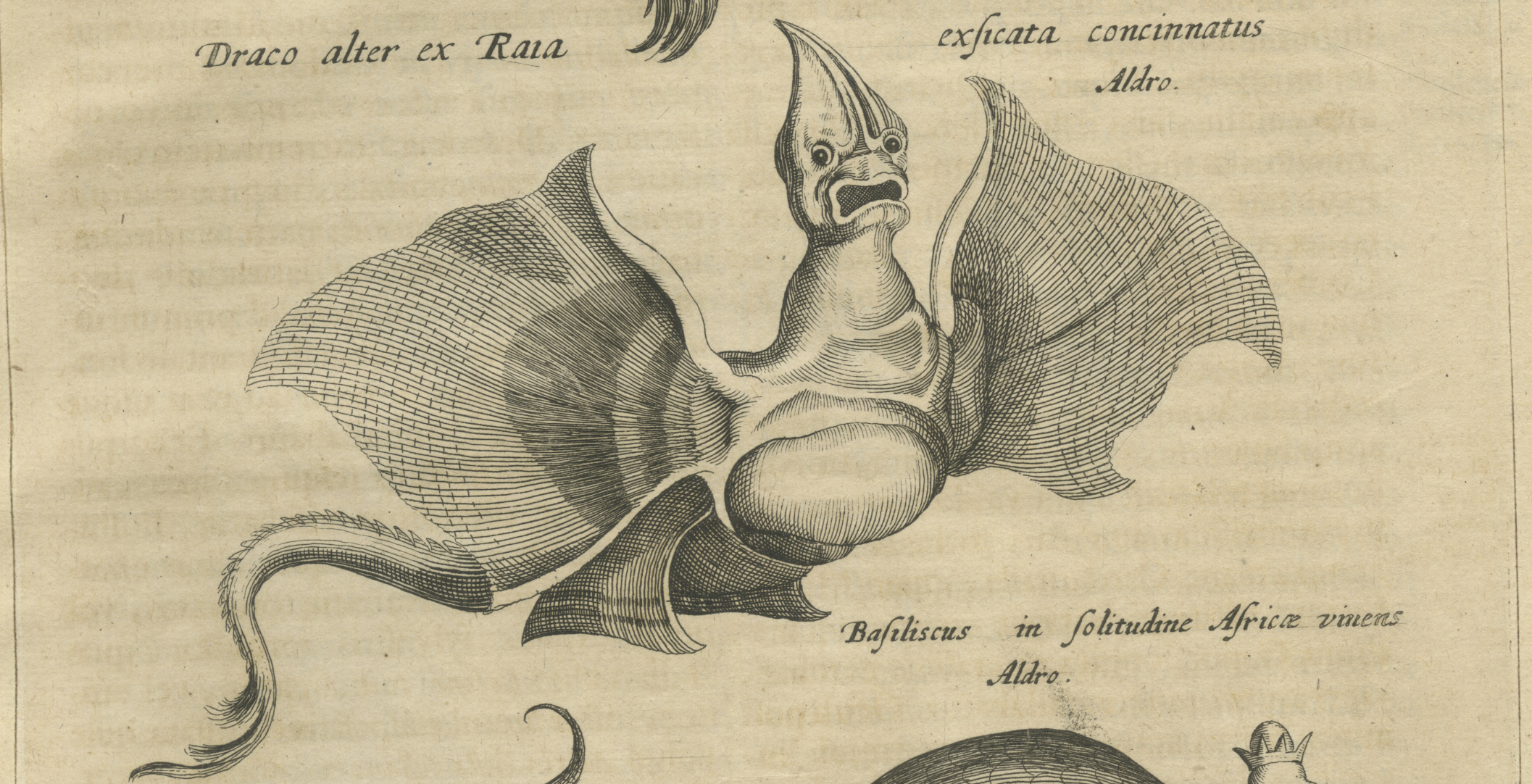

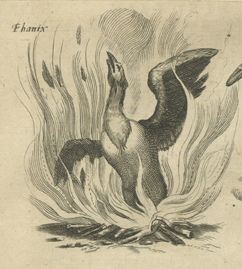

A student of philosophy, theology, and medicine, Joannes Jonstanus also borrowed heavily from Biblical and ancient sources, and presented realistic animals next to mythical beasts. A number of his fanciful illustrations from his Historiae Naturalis (1657) appear here. They include the draco, the griffin, the harpy, the leucurcuta, the lion, the merman, and the phoenix. Of particular interest is the martigora. Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle described the beast as:

Large and rough as a lion, ...its ears and face are like those of a man; its eye is grey, and its body red; it has a tail like a land Scorpion, in which there is a sting; ...it utters a noise resembling the united sound of a pipe and a trumpet; it is not less swift of foot than a stag, and is wild, and devours men.

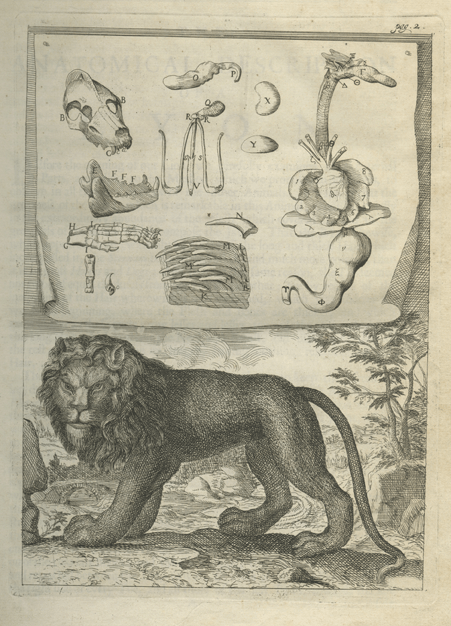

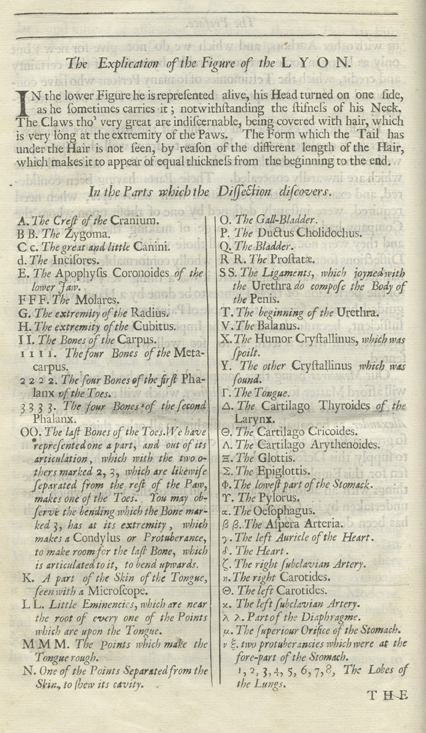

Turning away from fantasy, naturalists of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries began to utilize comparative anatomy to better understand animals. In Memoirs for a Natural History of Animals (1688), Englishman Alexander Pitfield depicted animals like the lion alongside its internal organs. Following the illustrations are detailed descriptions of each of the animal's parts, complete with comparisons with other animals. Observation was becoming more important to naturalists, replacing the reliance on classical texts.

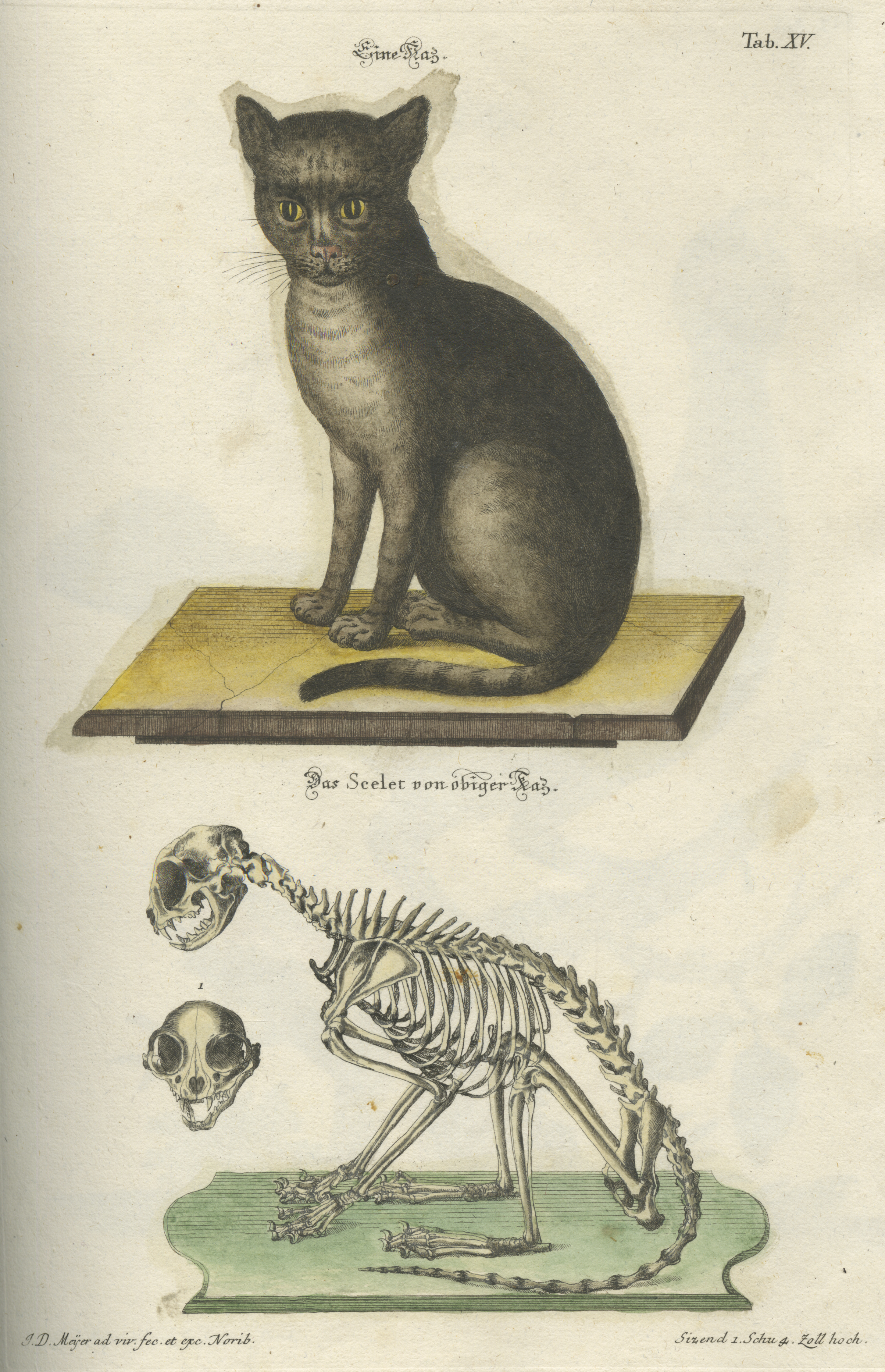

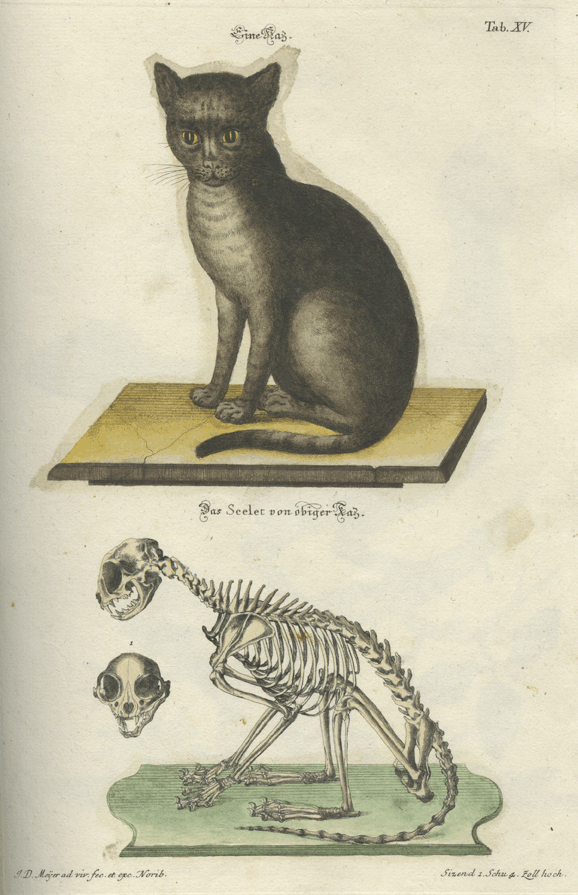

Similar to Pitfield's lion is the colored illustration of a cat by Johann Daniel Meyer. The feline is presented in living form, with its skeletal representation posed directly below. Eighteenth-century German engraver Meyer, in Vorstellungen allerley Thiere mit ihren Gerippen (1752), presents over 100 animals in this colorful, yet macabre fashion. Meyer also worked as a miniature painter, and his remarkable skill is apparent in the detail of his anatomical engravings.

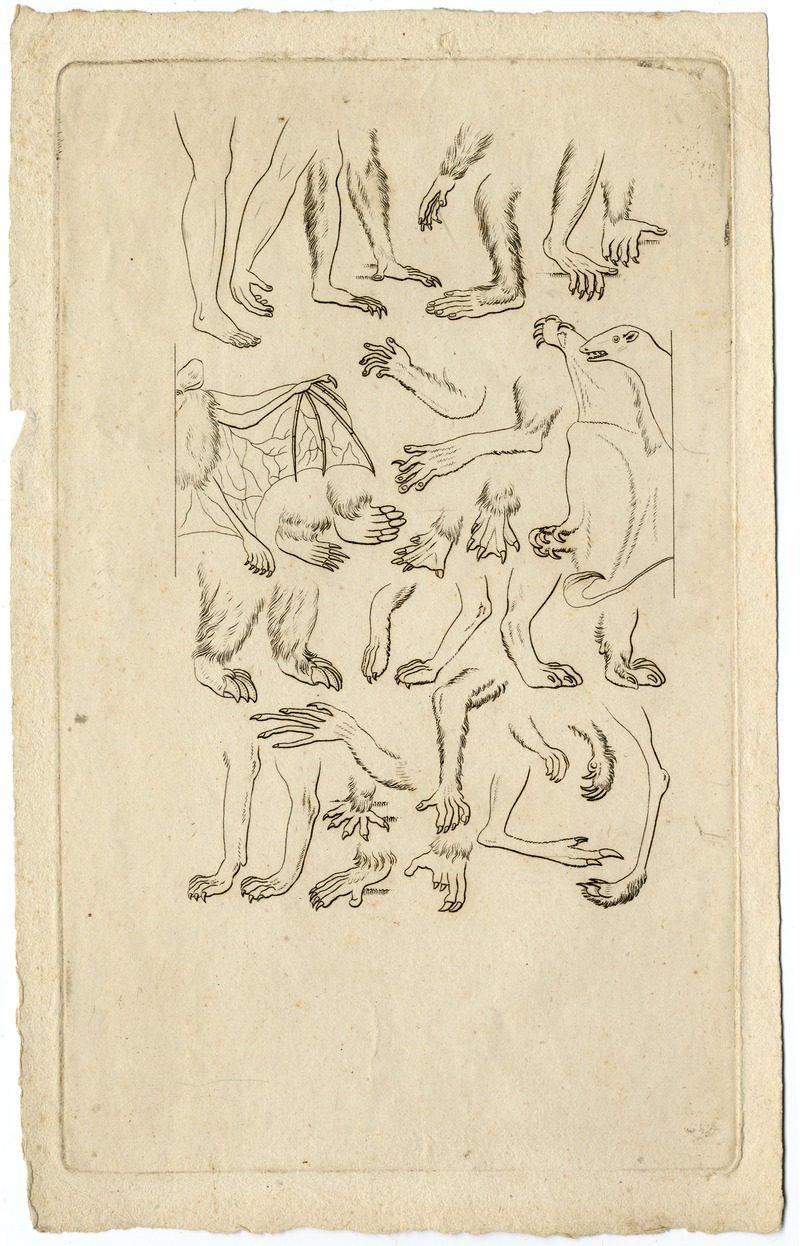

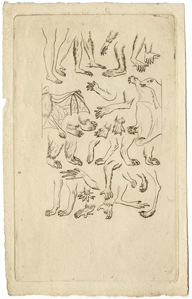

The final image, "Homology: Arms and Legs," is a later work, from the nineteenth century. It suggests the relationship between several animals based on similarity in form of body parts. Naturalists have pondered different ways of classifying animals, of discovering a taxonomy to catalog and describe them. Comparing physical composition is one way of achieving this.

Image Gallery

-

Phoenix

Joannes Jonstonus (1603-1675). Historiae Naturalis; Phoenix (Tab. 62); 1657. (590 J73 vol. 2)

First introduced by ancient Greek historian Herodotus (484-425 BC), this mythical bird was popular with later Christian sources. Blessed with remarkable plumage and colors, the bird is noteworthy for its unique ability of rebirth and eternal life. After being consumed by flames and apparently perishing, the bird regenerates itself and rises on the third day from the ashes.

-

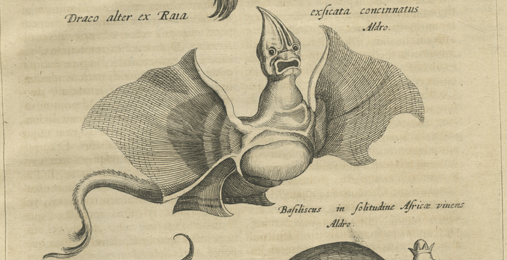

Draco

Joannes Jonstonus (1603-1675). Historiae Naturalis; Draco alter ex Raia (Tab. XI); 1657. (590 J73 vol. 2)

This creature is an example of an early modern hoax. Jonstonus labeled the image "Draco alter ex Raia exsiccate concinnatus," which roughly translates to "Another dragon fashioned from dried Raia." It is a drawing of a deceased ray that has been fashioned to look like a dragon. Such an effort is also called a "Jenny Haniver."

-

Saint Anthony

Book of Hours. Saint Anthony Abbot, circa 1475. Detmar Basse Müller Book of Hours. Manuscript. (Mss.264.02 R66)

Books of hours were among the most common devotional texts of the Middle Ages. Produced throughout western Europe until the early sixteenth century, books of hours were important status items, often elaborately illuminated, that might be tailored to the specific tastes of well-heeled clients to reflect interests in particular saints or to incorporate other elements of their personal lives and religious, political, or social commitments.

-

Harpy

Joannes Jonstonus (1603-1675). Historiae Naturalis; Harpy (Tab. 62); 1657. (590 J73 vol. 2)

The harpy can be found in ancient Greek myth. The creature has the head of a woman, with the body of a vulture. A malign beast, the harpy is often associated with pain and torment. Jason and the Argonauts rescued the blind Phineus from harpies who continually robbed him of his food. In other myths, harpies were depicted carrying off persons to the underworld and inflicting punishment on them.

-

Griffon

Joannes Jonstonus (1603-1675). Historiae Naturalis; Griffon (Tab. 62); 1657. (590 J73 vol. 2)

Most widely appearing in stories relating to ancient Greece, this creature also can also be found in the mythology of ancient Persia and ancient Egypt. The griffin has the head and wings of an eagle and the body of a lion. A combination of the "King of the Air" and the "King of Beasts," it was a revered creature and was widely used in European heraldry. According to legend, Alexander the Great once fought and captured a griffin. After taming the beast, he rode on its back and flew over his conquered lands.

-

Anthra pomorphos

Joannes Jonstonus (1603-1675). Historiae Naturalis; Anthra pomorphos (Tab. XL); 1657. (590 J73 vol. 1)

Mermen and mermaids have appeared throughout worldwide myth. The ancient Babylonians and Sumerians believed in the existence of half-man, half-fish creatures. The Greeks and Romans also incorporated these creatures in their mythology. Sailors throughout the ages have claimed to have encountered them. In 1493, Christopher Columbus thought he saw three mermaids off the coast of present-day Haiti: "They were not as beautiful as they are painted, although to some extent they have a human appearance in the face."

-

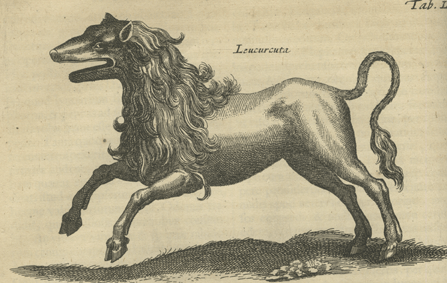

Leucurcuta

Joannes Jonstonus (1603-1675). Historiae Naturalis; Leucurcuta (Tab. LII); 1657. (590 J73 vol. 1)

The ancient Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder (23-79) first described the Leucurcuta. It is purported to be the offspring of a mythical wolf and lion. It has the head of a badger, the chest and tail of a lion, and the body of a stag. The Leucurcuta was said to have the ability to speak with a human voice, through which it would lure unsuspecting human victims. Fortunately, a mythical creature.

-

Leo Minor

Joannes Jonstonus (1603-1675). Historiae Naturalis; Leo Minor (Tab. LII); 1657. (590 J73 vol. 1)

A Polish-born physician of Scottish descent, Jonstonus is best known for his four-volume work on natural history, Historiae Naturalis. Jonstonus was well-traveled and well-educated, possessing degrees from the Universities of Saint Andrews, Cambridge, and Leiden. His work Historiae Naturalis is largely a compilation of the efforts of earlier writers, in particular Conrad Gesner and Ulysses Aldrovani. Comprising separate volumes on quadrupeds, fish, birds, and serpents, the work is notable for its scope and illustrations. Pictured here is Leo Minor, "a smaller lion."

-

Martigora

Joannes Jonstonus (1603-1675). Historiae Naturalis; Martigora (Tab. LII); 1657. (590 J73 vol. 1)

A creature that was once professed to terrorize the Asian continent, the Martigora possessed the head of a man, the body of a lion, and the tail of a scorpion. First mentioned by the ancient Greek physician Ctesias, the creature was also described by the philosopher Aristotle (384-322 BC):

It is as large and rough as a lion, and has similar feet, but its ears and face are like those of a man; its eye is grey, and its body red; it has a tail like a land scorpion, in which there is a sting; it darts forth the spines with which it is covered, instead of hair, and it utters a noise resembling the united sound of a pipe and a trumpet; it is not less swift of foot than a stag, and is wild, and devours men.

-

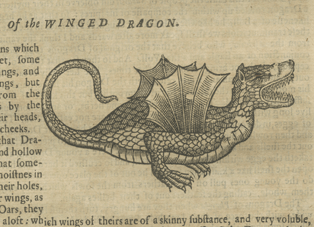

Dragons

Edward Topsell (1572-1625). History of the Four-Footed Beasts and Serpents, Dragons, 1658. (590 T62)

Topsell recounted numerous stories featuring dragons. One of the most familiar to his readers was the following account from the Bible, featuring the battle of Archangel Michael with the dragon:

And there appeared another wonder in heaven; and behold a great red dragon, having seven heads and ten horns.... And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, and prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven. And the great dragon was cast out, that old serpent called the Devil, and Satan, which deceiveth the whole world, and his angels were cast out with him (Revelation 12: 3, 7-9).

-

Winged Dragon

Edward Topsell (1572-1625). History of the Four-Footed Beasts and Serpents, Winged Dragon, 1658. (590 T62)

Topsell claimed that winged dragons plagued early modern Europe. According to him, they attacked the German town of Stiria in 1543 and "did bite and wound many men incurably." A Frenchman was able to slay one of the beasts in another attack:

There was a Dragon or Winged-serpent brought unto Francis the French-King when he lay at Saneton by a certain Country-man, who had slain the same Serpent himself with a spade, when it set upon him in the fields to kill him. And this thing was witnessed by many learned and credible men which saw the same: and they thought it was not bred into that country, but rather driven by the wind thither from some foreign nation.

Sepedon

Edward Topsell (1572-1625). History of the Four-Footed Beasts and Serpents, Sepedon, 1658. (590 T62)

Distinct from the modern genus of sepedon, a marsh fly, Topsell’s sepedon is a poisonous serpent. The Greek definition of "sepedon" is "rottenness, decay; a serpent whose bite causes mortification." In describing the creature, Topsell cited Nicander of Colophon, an ancient Greek poet who wrote about venomous animals.

-

Sepedon

Edward Topsell (1572-1625). History of the Four-Footed Beasts and Serpents, Sepedon, 1658. (590 T62)

Sea serpents were long thought to menace the seas. Topsell references the work of Olaus Magnus, who in 1555 wrote History of the Northern Peoples. In that work, Magnus tells of a 120-foot long serpent which haunted the coast of Norway. Topsell notes that such sea serpents are:

Very dangerous and hurtful to the Sea-men in calms and still weather, for they lift themselves above the hatches, and suddenly catch a man in their mouths, and so draw him into the Sea out of the ship; and many times they overthrow in the waters a laden vessel of great quantity, with all the wares therein contained.

-

Lyon

Alexander Pitfield (1658-1728). Memoirs for a Natural History of Animals, Lyon, 1688. (596 P42m.p)

Pitfield was an active fellow of the Royal Society and served in leadership positions on the society’s council and as treasurer. He also was active in politics, having served in the House of Commons as a Member of Parliament for Bridport from 1698-1708.

-

Meyer Cat

Johann Daniel Meyer (1713-1752). Johann Daniel Meyers Vorstellungen allerley Thiere mit ihren Gerippen, Cat (tab. xv), 1752. (590 M57)

According to an English proverb, "In a cat’s eye, all things belong to cats." A 2004 archeological dig in Cyprus has shown that domestication of cats may have begun earlier than was previously thought. The remains of a cat buried with a human in the Neolithic village of Shillourokambos suggest that the process of cat domestication had begun as early as 7,500 BC. The previous prevailing thought had credited the ancient Egyptians with starting cat domestication in 2,000 BC.

-

Homology

Homology: Arms and Legs, n.d. Benjamin Smith Barton Papers. (Mss.B.B284d)

Homology is defined as "likeness in structure between parts of different organisms (as the wing of a bat and the human arm) due to evolutionary differentiation from a corresponding part in a common ancestor" (Merriam-Webster).