Unearthing Stories: Sketching Splendor Spotlight, Part I

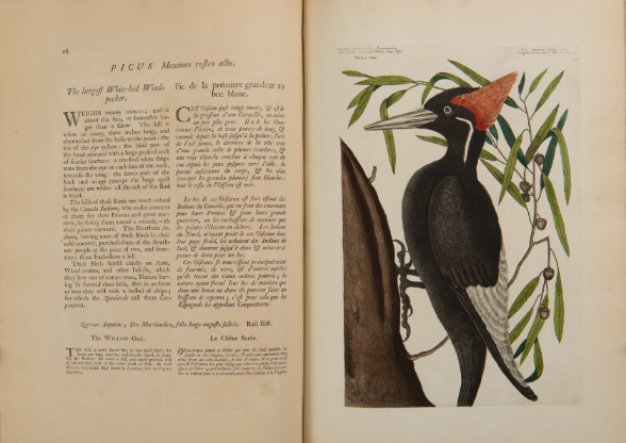

Header Image: The Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, vol 1, Mark Catesby, 1771, London, 1771 (3rd edition). APS.

A picture is worth a thousand words, meaning it can also hold many stories.

Behind every natural history image lies the labor and expertise of many hands. Sometimes those people get credit. However, many times they go unnamed and their stories do not get told. This blog will take a closer look at our latest exhibition, Sketching Splendor: American Natural History, 1750-1850, and some objects in it that have these extra stories behind them.

The Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, vol 1 by English naturalist Mark Catesby was the first major illustrated natural history text of plants and animals of both the North American colonies and the Caribbean. Catesby made two trips to the North American continent between 1712 and 1726. In the picture below, Catesby was one of these early naturalists documenting not just the animals, but their ecological context.

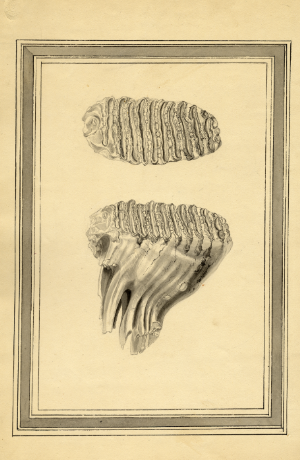

Throughout his travels in the American Southeast, Catesby drew on Native American expertise—especially in the Carolinas, where he relied on Cherokee or possibly Chickasaw guides. However, Catesby doesn’t give the names of these Indigenous experts. During this time, Catesby also made his way to Stono Plantation in South Carolina, where enslaved people had unearthed huge mysterious teeth. When Catesby spoke with the enslaved people there, they observed that these were similar to elephant teeth back home. They deduced correctly that there was a connection between these mysterious specimens—which in fact belonged to a mammoth—and elephants, as the extinct and modern species are related. In this instance, they used comparative anatomy and their own expertise to identify this species as being connected to elephants. Below is an image of a mammoth molar from the APS Library collections for reference. We unfortunately do not know the names of the people who helped identify these fossils. However, we find their stories in letters left behind about the teeth.

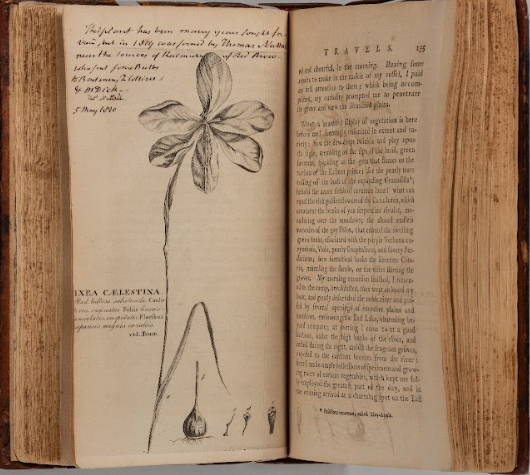

The next object begins with William Bartram’s expedition to the American Southeast from 1773 to 1777, documented in his book Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida. Throughout his trip, Bartram relied on both patronage from plantations and the labor of enslaved Africans. At one point, Bartram talks about traveling to St. John and related, “being now in readiness to prosecute our voyage to St. John’s we set sail in a handsome pleasure-boat, manned with four stout negro slaves, to row in case of necessity.” The Southeast was new to Bartram, who relied on the experience and expertise of enslaved people who knew this territory and how to get around.

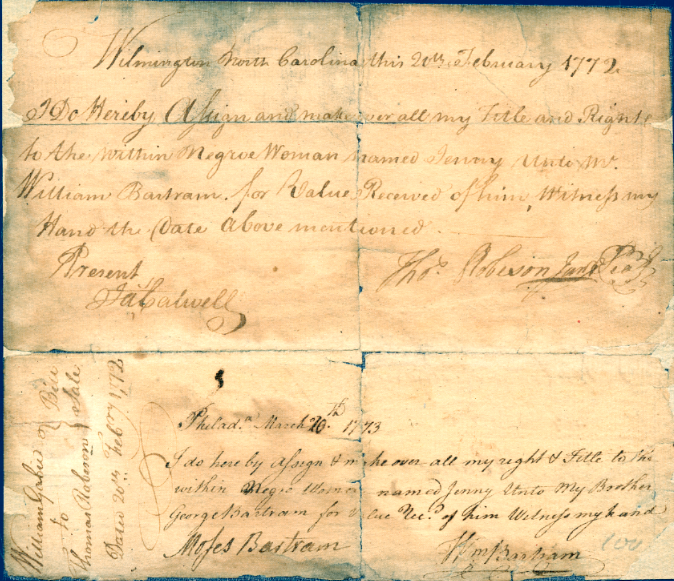

Bartram also enslaved people himself. Prior to this expedition, he enslaved six people on his East Florida plantation. This plantation soon went under, and it is still not quite known what became of these people afterwards. However, we do know that Bartram later enslaved a woman called Jenny, whose name is recorded on a bill of sale. Bartram enslaved Jenny from 1772 until 1773, when Bartram’s relatives would go on to sell Jenny on his behalf. The end date is interesting to note as well, as William would begin his expedition soon after. Perhaps this money from the sale was also used to fund his Travels expedition.

Most of these objects are on display (except for the mammoth molar) in our current exhibition, Sketching Splendor: American Natural History, 1750-1850 and together they show how early American natural history relied on the labor of many more people than those who received credit. Check back for part two of this blog to learn more.