The Right to Tell

When coming to the American Philosophical Society as an intern with the Native American Scholars Initiative (NASI), I was thinking of something my dad has repeated quite frequently: we need to know our history in order to know who we are today.

I am a citizen of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina. We are state-recognized and commonly referred to as an amalgamation of other tribes and peoples. Our history is complicated and rooted in resistance to erasure.

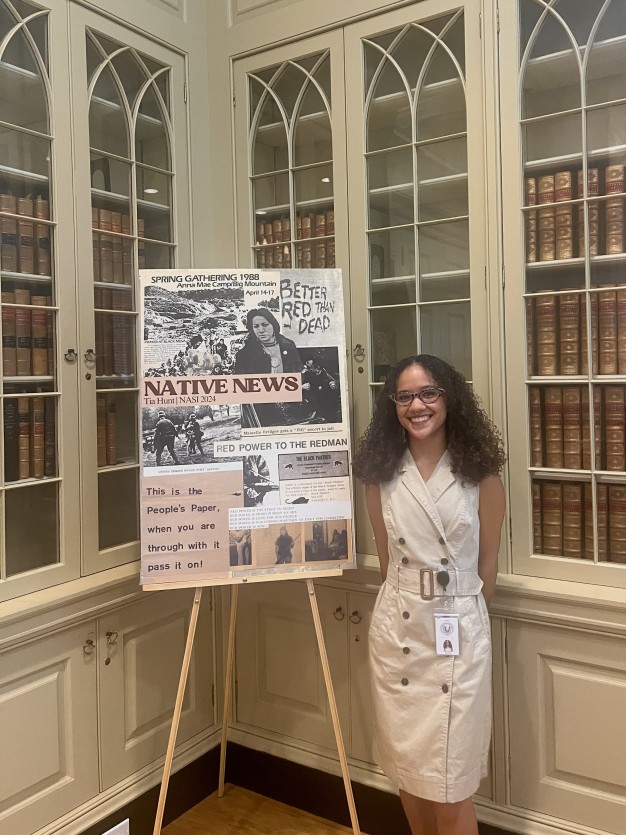

There wasn’t much that I was expecting to find about Lumbees in the APS archive. When I first arrived, this very much rang true. Much of the mentions of Lumbee people were included in projects related to neighboring tribes or the region as a whole. In need of a topic with more breadth of material, I switched to something else that I hold close to home: political activism and information distribution. Native-run newspapers and how they were distributed between and among communities became my new focus.

I went into the reading room to explore Native-run publications that had been set aside for me by staff of the Center for Native American and Indigenous Research (CNAIR). Also in the material I examined were two books related to the American Indian Movement created by Indigenous people that took part in or reported on the movement.

The first item I looked at was the book Trail of Broken Treaties: B.I.A. I’m Not Your Indian Anymore, which was edited by Akwesasne Notes, a St. Regis Mohawk Reservation produced newspaper from 1969 to 1997. It was an Indigenous recounting of the Trail of Broken Treaties, which was a caravan of Indigenous Americans and allies ending in Washington, D.C. to bring awareness to Native peoples’ demands and ended with an occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs building. The book included first-hand accounts and reporting from Akwesasne Notes, an Indigenous run newspaper, in order to counter non-Native retellings of the events. I was in love with the merging of Native newspapers with photography and personal accounts from the protests because of its ability to highlight the different experiences of people present during the actions.

Within the first 10 pages of the book, I found an unexpected reference to Indians of Robeson County. As I continued to flip through, our people were present all throughout the retelling. Most notably for me, was an article explaining the court cases of four Robeson County Indians who allegedly took papers from the Bureau of Indian Affairs during the building occupation. One of the men denied any involvement, but said that if he did take the papers it would’ve been within his right. As a Lumbee man, he said his history was hidden from him and taking the papers would’ve been in service towards a journey of knowing who we truly are. His comments paralleled ones I’ve heard from my dad on the importance of learning our identity.

Soon after reading this, I took part in a conversation with other NASI interns and staff of CNAIR to discuss “The Right to Know,” an article by Jennifer O’Neal. In her piece she talks about the importance of Indigenous archives, how they have been used in the past, and how they can be used in the future to accomplish the goals that the influential Vine Deloria has previously outlined. She quotes Deloria in saying Indians have a right to know “the past, to know the traditional alternatives advocated by their ancestors, to know the specific experiences of their communities, and to know about the world that surrounds them…” My feelings, my father’s feelings, and the feelings of the Lumbee man fighting charges for wanting to know his history were all validated and expanded upon in ways I had never previously seen.

Deloria’s work from almost fifty years ago continues to highlight the importance of accessibility to information on Native history for Native people. The newspapers and recounting of events created by Native people that I was able to research this summer was a reminder for me of the importance of both the right to know and the right to tell our stories.